标签:

Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) are popular models that have shown great promise in many NLP tasks. But despite their recent popularity I’ve only found a limited number of resources that throughly explain how RNNs work, and how to implement them. That’s what this tutorial is about. It’s a multi-part series in which I’m planning to cover the following:

As part of the tutorial we will implement a recurrent neural network based language model. The applications of language models are two-fold: First, it allows us to score arbitrary sentences based on how likely they are to occur in the real world. This gives us a measure of grammatical and semantic correctness. Such models are typically used as part of Machine Translation systems. Secondly, a language model allows us to generate new text (I think that’s the much cooler application). Training a language model on Shakespeare allows us to generate Shakespeare-like text. This fun post by Andrew Karpathy demonstrates what character-level language models based on RNNs are capable of.

I’m assuming that you are somewhat familiar with basic Neural Networks. If you’re not, you may want to head over to Implementing A Neural Network From Scratch, which guides you through the ideas and implementation behind non-recurrent networks.

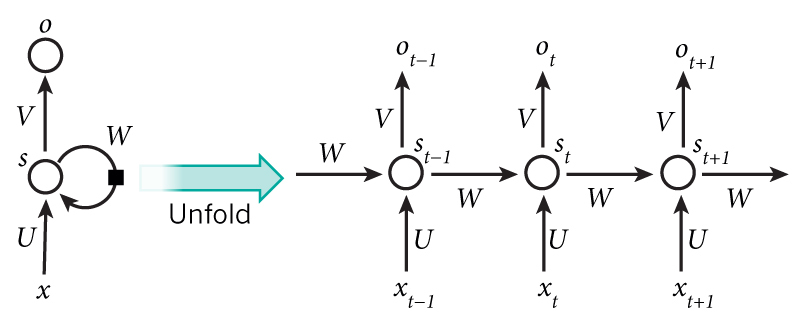

The idea behind RNNs is to make use of sequential information. In a traditional neural network we assume that all inputs (and outputs) are independent of each other. But for many tasks that’s a very bad idea. If you want to predict the next word in a sentence you better know which words came before it. RNNs are called recurrent because they perform the same task for every element of a sequence, with the output being depended on the previous computations. Another way to think about RNNs is that they have a “memory” which captures information about what has been calculated so far. In theory RNNs can make use of information in arbitrarily long sequences, but in practice they are limited to looking back only a few steps (more on this later). Here is what a typical RNN looks like:

A recurrent neural network and the unfolding in time of the computation involved in its forward computation. Source: Nature

A recurrent neural network and the unfolding in time of the computation involved in its forward computation. Source: Nature

The above diagram shows a RNN being unrolled (or unfolded) into a full network. By unrolling we simply mean that we write out the network for the complete sequence. For example, if the sequence we care about is a sentence of 5 words, the network would be unrolled into a 5-layer neural network, one layer for each word. The formulas that govern the computation happening in a RNN are as follows:

There are a few things to note here:

RNNs have shown great success in many NLP tasks. At this point I should mention that the most commonly used type of RNNs are LSTMs, which are much better at capturing long-term dependencies than vanilla RNNs are. But don’t worry, LSTMs are essentially the same thing as the RNN we will develop in this tutorial, they just have a different way of computing the hidden state. We’ll cover LSTMs in more detail in a later post. Here are some example applications of RNNs in NLP (by non means an exhaustive list).

Given a sequence of words we want to predict the probability of each word given the previous words. Language Models allow us to measure how likely a sentence is, which is an important input for Machine Translation (since high-probability sentences are typically correct). A side-effect of being able to predict the next word is that we get a generative model, which allows us to generate new text by sampling from the output probabilities. And depending on what our training data is we can generate all kinds of stuff. In Language Modeling our input is typically a sequence of words (encoded as one-hot vectors for example), and our output is the sequence of predicted words. When training the network we set since we want the output at step

to be the actual next word.

Research papers about Language Modeling and Generating Text:

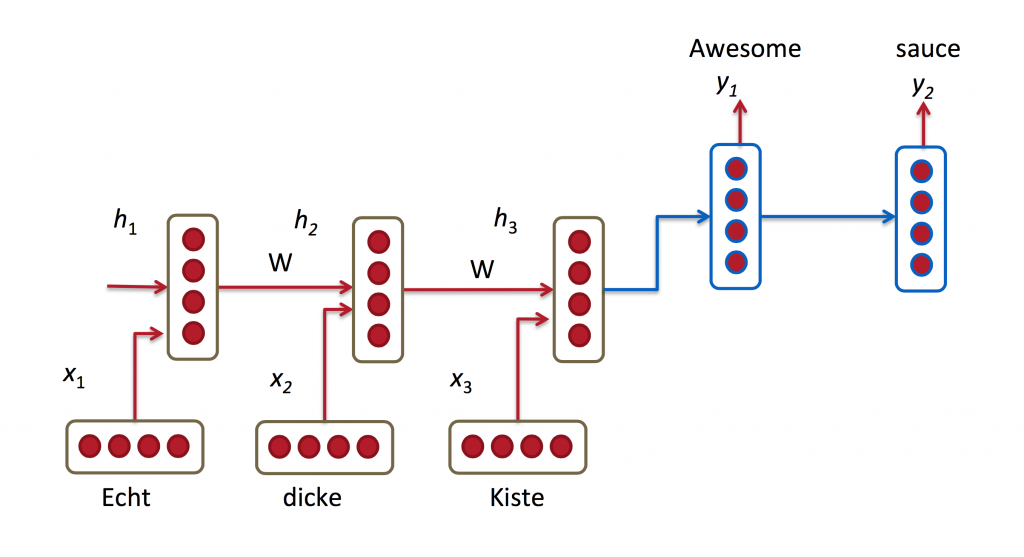

Machine Translation is similar to language modeling in that our input is a sequence of words in our source language (e.g. German). We want to output a sequence of words in our target language (e.g. English). A key difference is that our output only starts after we have seen the complete input, because the first word of our translated sentences may require information captured from the complete input sequence.

RNN for Machine Translation. Image Source: http://cs224d.stanford.edu/lectures/CS224d-Lecture8.pdf

RNN for Machine Translation. Image Source: http://cs224d.stanford.edu/lectures/CS224d-Lecture8.pdf

Research papers about Machine Translation:

Given an input sequence of acoustic signals from a sound wave, we can predict a sequence of phonetic segments together with their probabilities.

Research papers about Speech Recognition:

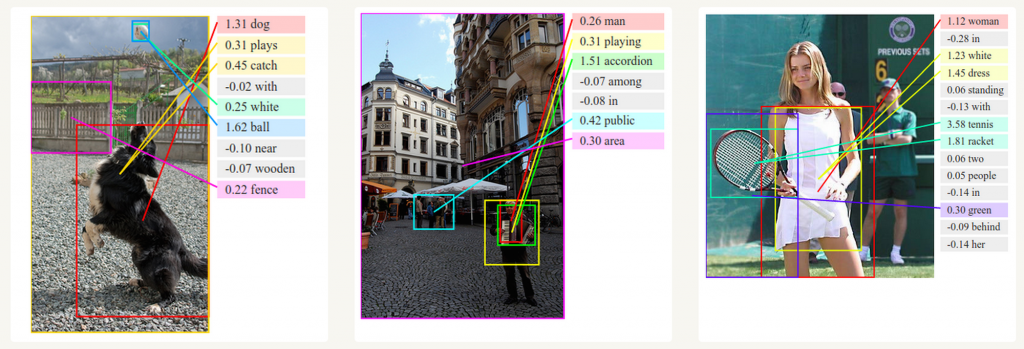

Together with convolutional Neural Networks, RNNs have been used as part of a model togenerate descriptions for unlabeled images. It’s quite amazing how well this seems to work. The combined model even aligns the generated words with features found in the images.

Deep Visual-Semantic Alignments for Generating Image Descriptions. Source: http://cs.stanford.edu/people/karpathy/deepimagesent/

Deep Visual-Semantic Alignments for Generating Image Descriptions. Source: http://cs.stanford.edu/people/karpathy/deepimagesent/

Training a RNN is similar to training a traditional Neural Network. We also use the backpropagation algorithm, but with a little twist. Because the parameters are shared by all time steps in the network, the gradient at each output depends not only on the calculations of the current time step, but also the previous time steps. For example, in order to calculate the gradient at we would need to backpropagate 3 steps and sum up the gradients. This is called Backpropagation Through Time (BPTT). If this doesn’t make a whole lot of sense yet, don’t worry, we’ll have a whole post on the gory details. For now, just be aware of the fact that vanilla RNNs trained with BPTT have difficulties learning long-term dependencies (e.g. dependencies between steps that are far apart) due to what is called the vanishing/exploding gradient problem. There exists some machinery to deal with these problems, and certain types of RNNs (like LSTMs) were specifically designed to get around them.

Over the years researchers have developed more sophisticated types of RNNs to deal with some of the shortcomings of the vanilla RNN model. We will cover them in more detail in a later post, but I want this section to serve as a brief overview so that you are familiar with the taxonomy of models.

Bidirectional RNNs are based on the idea that the output at time may not only depend on the previous elements in the sequence, but also future elements. For example, to predict a missing word in a sequence you want to look at both the left and the right context. Bidirectional RNNs are quite simple. They are just two RNNs stacked on top of each other. The output is then computed based on the hidden state of both RNNs.

Deep (Bidirectional) RNNs are similar to Bidirectional RNNs, only that we now have multiple layers per time step. In practice this gives us a higher learning capacity (but we also need a lot of training data).

LSTM networks are quite popular these days and we briefly talked about them above. LSTMs don’t have a fundamentally different architecture from RNNs, but they use a different function to compute the hidden state. The memory in LSTMs are called cells and you can think of them as black boxes that take as input the previous state and current input

. Internally these cells decide what to keep in (and what to erase from) memory. They then combine the previous state, the current memory, and the input. In turns out that these types of units are very efficient at capturing long-term dependencies. LSTMs can be quite confusing in the beginning but if you’re interested in learning more this post has an excellent explanation.

So far so good. I hope you’ve gotten a basic understanding of what RNNs are and what they can do. In the next post we’ll implement a first version of our language model RNN using Python and Theano. Please leave questions in the comments!

Recurrent Neural Networks Tutorial, Part 1 – Introduction to RNNs

标签:

原文地址:http://www.cnblogs.com/yymn/p/4820158.html