标签:released when cgi services sts sid url workload ade

If Protocol Buffers is the lingua franca of individual data record at Google, then the Sorted String Table (SSTable) is one of the most popular outputs for storing, processing, and exchanging datasets. As the name itself implies, an SSTable is a simple abstraction to efficiently store large numbers of key-value pairs while optimizing for high throughput, sequential read/write workloads.

Unfortunately, the SSTable name itself has also been overloaded by the industry to refer to services that go well beyond just the sorted table, which has only added unnecessary confusion to what is a very simple and a useful data structure on its own. Let‘s take a closer look under the hood of an SSTable and how LevelDB makes use of it.

Imagine we need to process a large workload where the input is in Gigabytes or Terabytes in size. Additionally, we need to run multiple steps on it, which must be performed by different binaries - in other words, imagine we are running a sequence of Map-Reduce jobs! Due to size of input, reading and writing data can dominate the running time. Hence, random reads and writes are not an option, instead we will want to stream the data in and once we‘re done, flush it back to disk as a streaming operation. This way, we can amortize the disk I/O costs. Nothing revolutionary, moving right along.

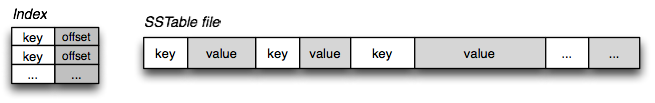

A "Sorted String Table" then is exactly what it sounds like, it is a file which contains a set of arbitrary, sorted key-value pairs inside. Duplicate keys are fine, there is no need for "padding" for keys or values, and keys and values are arbitrary blobs. Read in the entire file sequentially and you have a sorted index. Optionally, if the file is very large, we can also prepend, or create a standalone key:offset index for fast access. That‘s all an SSTable is: very simple, but also a very useful way to exchange large, sorted data segments.

Once an SSTable is on disk it is effectively immutable because an insert or delete would require a large I/O rewrite of the file. Having said that, for static indexes it is a great solution: read in the index, and you are always one disk seek away, or simply memmap the entire file to memory. Random reads are fast and easy.

Random writes are much harder and expensive, that is, unless the entire table is in memory, in which case we‘re back to simple pointer manipulation. Turns out, this is the very problem that Google‘s BigTable set out to solve: fast read/write access for petabyte datasets in size, backed by SSTables underneath. How did they do it?

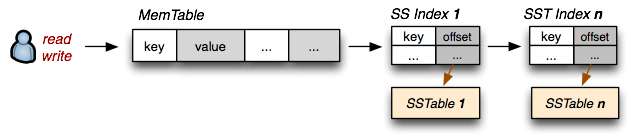

We want to preserve the fast read access which SSTables give us, but we also want to support fast random writes. Turns out, we already have all the necessary pieces: random writes are fast when the SSTable is in memory (let‘s call it MemTable), and if the table is immutable then an on-disk SSTable is also fast to read from. Now let‘s introduce the following conventions:

SSTable indexes are always loaded into memoryMemTable indexWhat have we done here? Writes are always done in memory and hence are always fast. Once the MemTable reaches a certain size, it is flushed to disk as an immutable SSTable. However, we will maintain all the SSTable indexes in memory, which means that for any read we can check the MemTable first, and then walk the sequence of SSTable indexes to find our data. Turns out, we have just reinvented the "The Log-Structured Merge-Tree" (LSM Tree), described by Patrick O‘Neil, and this is also the very mechanism behind "BigTable Tablets".

This "LSM" architecture provides a number of interesting behaviors: writes are always fast regardless of the size of dataset (append-only), and random reads are either served from memory or require a quick disk seek. However, what about updates and deletes?

Once the SSTable is on disk, it is immutable, hence updates and deletes can‘t touch the data. Instead, a more recent value is simply stored in MemTable in case of update, and a "tombstone" record is appended for deletes. Because we check the indexes in sequence, future reads will find the updated or the tombstone record without ever reaching the older values! Finally, having hundreds of on-disk SSTables is also not a great idea, hence periodically we will run a process to merge the on-disk SSTables, at which time the update and delete records will overwrite and remove the older data.

Take an SSTable, add a MemTable and apply a set of processing conventions and what you get is a nice database engine for certain type of workloads. In fact, Google‘s BigTable, Hadoop‘s HBase, and Cassandra amongst others are all using a variant or a direct copy of this very architecture.

Simple on the surface, but as usual, implementation details matter a great deal. Thankfully, Jeff Dean and Sanjay Ghemawat, the original contributors to the SSTable and BigTable infrastructure at Google released LevelDB earlier last year, which is more or less an exact replica of the architecture we‘ve described above:

Designed to be the engine for IndexDB in WebKit (aka, embedded in your browser), it is easy to embed, fast, and best of all, takes care of all the SSTable and MemTable flushing, merging and other gnarly details.

LevelDB is a library, not a standalone server or service - although you could easily implement one on top. To get started, grab your favorite language bindings (ruby), and let‘s see what we can do:

require ‘leveldb‘ # gem install leveldb-ruby

db = LevelDB::DB.new "/tmp/db"

db.put "b", "bar"

db.put "a", "foo"

db.put "c", "baz"

puts db.get "a" # => foo

db.each do |k,v|

p [k,v] # => ["a", "foo"], ["b", "bar"], ["c", "baz"]

end

db.to_a # => [["a", "foo"], ["b", "bar"], ["c", "baz"]]We can store keys, retrieve them, and perform a range scan all with a few lines of code. The mechanics of maintaining the MemTables, merging the SSTables, and the rest is taken care for us by LevelDB - nice and simple.

SSTable is a very simple and useful data structure - a great bulk input/output format. However, what makes the SSTable fast (sorted and immutable) is also what exposes its very limitations. To address this, we‘ve introduced the idea of a MemTable, and a set of "log structured" processing conventions for managing the many SSTables.

All simple rules, but as always, implementation details matter, which is why LevelDB is such a nice addition to the open-source database engine stack. Chances are, you will soon find LevelDB embedded in your browser, on your phone, and in many other places. Check out the LevelDB source, scan the docs, and take it for a spin.

SSTable and Log Structured Storage: LevelDB

标签:released when cgi services sts sid url workload ade

原文地址:http://www.cnblogs.com/cobbliu/p/6146273.html