标签:共享 指令 产品 通过 make time orm ogr ctime

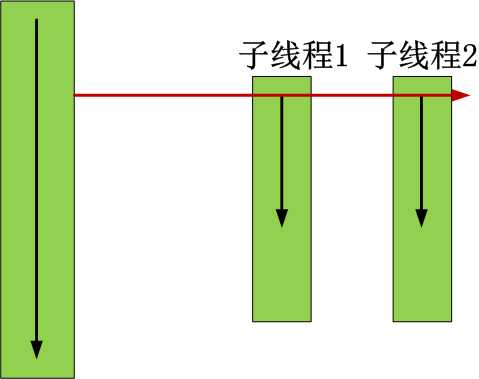

‘‘‘ 进程包括多个线程,线程之间切换的开销远小于进程之间切换的开销 线程一定是寄托于进程而存在的 进程:最小的资源管理单元 线程:最小的执行单元 python锁的机制,一个进程一把锁,一个进程一个时间只能取出一个线程,所以无法实现真正的进程中的线程并行 I/O密集型任务 计算密集型任务 ‘‘‘

import threading import time def countNum(n): # 定义某个线程要运行的函数 print("running on number:%s" %n) time.sleep(3) if __name__ == ‘__main__‘: t1 = threading.Thread(target=countNum,args=(23,)) #生成一个线程实例 t2 = threading.Thread(target=countNum,args=(34,)) t1.start() #启动线程 t2.start() print("ending!")

#继承Thread式创建 import threading import time class MyThread(threading.Thread): def __init__(self,num): threading.Thread.__init__(self) self.num=num def run(self): print("running on number:%s" %self.num) time.sleep(3) t1=MyThread(56) t2=MyThread(78) t1.start() t2.start() print("ending")

# join():在子线程完成运行之前,这个子线程的父线程将一直被阻塞。 # setDaemon(True): ‘‘‘ 将线程声明为守护线程,必须在start() 方法调用之前设置,如果不设置为守护线程程序会被无限挂起。 当我们在程序运行中,执行一个主线程,如果主线程又创建一个子线程,主线程和子线程 就分兵两路,分别运行,那么当主线程完成 想退出时,会检验子线程是否完成。如果子线程未完成,则主线程会等待子线程完成后再退出。但是有时候我们需要的是只要主线程 完成了,不管子线程是否完成,都要和主线程一起退出,这时就可以 用setDaemon方法啦‘‘‘ import threading from time import ctime,sleep import time def Music(name): print ("Begin listening to {name}. {time}".format(name=name,time=ctime())) sleep(3) print("end listening {time}".format(time=ctime())) def Blog(title): print ("Begin recording the {title}. {time}".format(title=title,time=ctime())) sleep(5) print(‘end recording {time}‘.format(time=ctime())) threads = [] t1 = threading.Thread(target=Music,args=(‘FILL ME‘,)) t2 = threading.Thread(target=Blog,args=(‘‘,)) threads.append(t1) threads.append(t2) if __name__ == ‘__main__‘: #t2.setDaemon(True) for t in threads: #t.setDaemon(True) #注意:一定在start之前设置 t.start() #t.join() #t1.join() #t2.join() # 考虑这三种join位置下的结果? print ("all over %s" %ctime())

daemon A boolean value indicating whether this thread is a daemon thread (True) or not (False). This must be set before start() is called, otherwise RuntimeError is raised. Its initial value is inherited from the creating thread; the main thread is not a daemon thread and therefore all threads created in the main thread default to daemon = False. The entire Python program exits when no alive non-daemon threads are left. 当daemon被设置为True时,如果主线程退出,那么子线程也将跟着退出, 反之,子线程将继续运行,直到正常退出。

Thread实例对象的方法

# isAlive(): 返回线程是否活动的。 # getName(): 返回线程名。 # setName(): 设置线程名。 threading模块提供的一些方法: # threading.currentThread(): 返回当前的线程变量。 # threading.enumerate(): 返回一个包含正在运行的线程的list。正在运行指线程启动后、结束前,不包括启动前和终止后的线程。 # threading.activeCount(): 返回正在运行的线程数量,与len(threading.enumerate())有相同的结果。

‘‘‘ 定义: In CPython, the global interpreter lock, or GIL, is a mutex that prevents multiple native threads from executing Python bytecodes at once. This lock is necessary mainly because CPython’s memory management is not thread-safe. (However, since the GIL exists, other features have grown to depend on the guarantees that it enforces.) ‘‘‘

Python中的线程是操作系统的原生线程,Python虚拟机使用一个全局解释器锁(Global Interpreter Lock)来互斥线程对Python虚拟机的使用。为了支持多线程机制,一个基本的要求就是需要实现不同线程对共享资源访问的互斥,所以引入了GIL。

GIL:在一个线程拥有了解释器的访问权之后,其他的所有线程都必须等待它释放解释器的访问权,即使这些线程的下一条指令并不会互相影响。

在调用任何Python C API之前,要先获得GIL

GIL缺点:多处理器退化为单处理器;优点:避免大量的加锁解锁操作

‘‘‘ 2.3.1 GIL的早期设计 Python支持多线程,而解决多线程之间数据完整性和状态同步的最简单方法自然就是加锁。 于是有了GIL这把超级大锁,而当越来越多的代码库开发者接受了这种设定后,他们开始大量依赖这种特性(即默认python内部对象是thread-safe的,无需在实现时考虑额外的内存锁和同步操作)。慢慢的这种实现方式被发现是蛋疼且低效的。但当大家试图去拆分和去除GIL的时候,发现大量库代码开发者已经重度依赖GIL而非常难以去除了。有多难?做个类比,像MySQL这样的“小项目”为了把Buffer Pool Mutex这把大锁拆分成各个小锁也花了从5.5到5.6再到5.7多个大版为期近5年的时间,并且仍在继续。MySQL这个背后有公司支持且有固定开发团队的产品走的如此艰难,那又更何况Python这样核心开发和代码贡献者高度社区化的团队呢? 2.3.2 GIL的影响 无论你启多少个线程,你有多少个cpu, Python在执行一个进程的时候会淡定的在同一时刻只允许一个线程运行。 所以,python是无法利用多核CPU实现多线程的。 这样,python对于计算密集型的任务开多线程的效率甚至不如串行(没有大量切换),但是,对于IO密集型的任务效率还是有显著提升的。 ‘‘‘

用multiprocessing替代Thread multiprocessing库的出现很大程度上是为了弥补thread库因为GIL而低效的缺陷。它完整的复制了一套thread所提供的接口方便迁移。唯一的不同就是它使用了多进程而不是多线程。每个进程有自己的独立的GIL,因此也不会出现进程之间的GIL争抢。 #coding:utf8 from multiprocessing import Process import time def counter(): i = 0 for _ in range(40000000): i = i + 1 return True def main(): l=[] start_time = time.time() for _ in range(2): t=Process(target=counter) t.start() l.append(t) #t.join() for t in l: t.join() end_time = time.time() print("Total time: {}".format(end_time - start_time)) if __name__ == ‘__main__‘: main() ‘‘‘ py2.7: 串行:6.1565990448 s 并行:3.1639978885 s py3.5: 串行:6.556925058364868 s 并发:3.5378448963165283 s ‘‘‘ 当然multiprocessing也不是万能良药。它的引入会增加程序实现时线程间数据通讯和同步的困难。就拿计数器来举例子,如果我们要多个线程累加同一个变量,对于thread来说,申明一个global变量,用thread.Lock的context包裹住三行就搞定了。而multiprocessing由于进程之间无法看到对方的数据,只能通过在主线程申明一个Queue,put再get或者用share memory的方法。这个额外的实现成本使得本来就非常痛苦的多线程程序编码,变得更加痛苦了。 总结:因为GIL的存在,只有IO Bound场景下得多线程会得到较好的性能 - 如果对并行计算性能较高的程序可以考虑把核心部分也成C模块,或者索性用其他语言实现 - GIL在较长一段时间内将会继续存在,但是会不断对其进行改进。

所以对于GIL,既然不能反抗,那就学会去享受它吧!

import threading,time ‘‘‘ 线程安全,多线程的问题: ‘‘‘ s=time.time() num=100 lock=threading.Lock() def sub(): # num-=1 #为什么出问题?因为这句本质上是num=num-1,‘num=‘是定义一个局部变量,‘num-1‘会调用num变量,先找局部,再找全局, # 现在局部正在定义num,所以局部找到了num,但是这时num还没有定义,所以报错 global num #(1)------------- # tmp=num # num=tmp-1 #(2)------------ # num-=1 #---------上面两种情况的执行结果一样,结果为0,因为执行速度快,每个线程获取num后 #----------(由于Python的gil锁限制,没有真正的多进程)马上就将新值覆盖了回去, # ----------所以其他线程执行的时候,都是基于上一个线程的处理结果上进行的------------------- # (3) # tmp=num # time.sleep(0.00001) # num=tmp-1 #---------上面这种情况执行结果不确定,因为赋值,更改之间存在时间差,所以在覆盖原数据之前可能切换到了其他线程, #---------重新对同一个值进行了操作,所以并不一定是基于哪个线程的执行结果执行的--------------------------- # (4) # tmp=num # time.sleep(0.1) # num=tmp-1 #------------上面这种情况是确定的,因为覆盖原值的间隔过长,使得所有线程执行的基础都是数据的初值 #---------------所以最后的每个线程都基于初值执行一次,然后不断覆盖之前线程的相同执行结果,最后结果是99 # (5) lock.acquire() #获取锁的占用权,在release之前,所有其他线程无法占用cpu。 tmp=num time.sleep(0.1) num=tmp-1 lock.release() #--------------这种情况用加锁的方法,保证了处理数据期间数据的安全,结果0 t={} for i in range(100): t[i]=threading.Thread(target=sub) t[i].start() for i in range(100): t[i].join() print("num:%s,time%s" %(num,time.time()-s))

所谓死锁: 是指两个或两个以上的进程或线程在执行过程中,因争夺资源而造成的一种互相等待的现象,若无外力作用,它们都将无法推进下去。此时称系统处于死锁状态或系统产生了死锁,这些永远在互相等待的进程称为死锁进程。

import threading import time mutexA = threading.Lock() mutexB = threading.Lock() class MyThread(threading.Thread): def __init__(self): threading.Thread.__init__(self) def run(self): self.fun1() self.fun2() def fun1(self): mutexA.acquire() # 如果锁被占用,则阻塞在这里,等待锁的释放 print ("I am %s , get res: %s---%s" %(self.name, "ResA",time.time())) mutexB.acquire() print ("I am %s , get res: %s---%s" %(self.name, "ResB",time.time())) mutexB.release() mutexA.release() def fun2(self): mutexB.acquire() print ("I am %s , get res: %s---%s" %(self.name, "ResB",time.time())) time.sleep(0.2) mutexA.acquire() print ("I am %s , get res: %s---%s" %(self.name, "ResA",time.time())) mutexA.release() mutexB.release() if __name__ == "__main__": print("start---------------------------%s"%time.time()) for i in range(0, 10): my_thread = MyThread() my_thread.start() ‘‘‘ 结果就是,线程一获取ab锁之后先后释放,然后线程二获得a锁,线程一获得b锁,然后线程一需要a锁,二需要b锁,然后就两个进程僵持住了 ‘‘‘

在Python中为了支持在同一线程中多次请求同一资源,python提供了可重入锁RLock。这个RLock内部维护着一个Lock和一个counter变量,counter记录了acquire的次数,从而使得资源可以被多次require。直到一个线程所有的acquire都被release,其他的线程才能获得资源。上面的例子如果使用RLock代替Lock,则不会发生死锁:(类似递归)

|

1

|

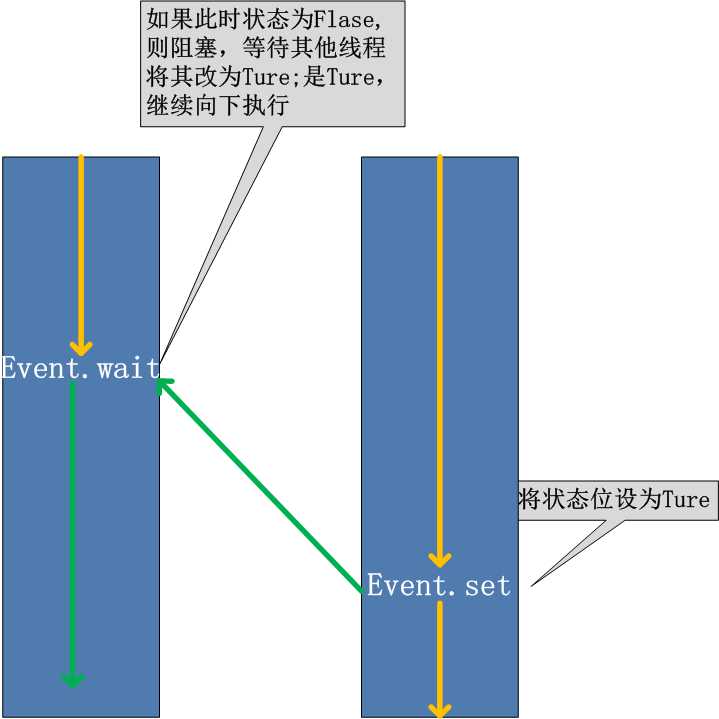

mutex = threading.RLock() |

‘‘‘ 线程的一个关键特性是每个线程都是独立运行且状态不可预测。如果程序中的其 他线程需要通过判断某个线程的状态来确定自己下一步的操作,这时线程同步问题就 会变得非常棘手。为了解决这些问题,我们需要使用threading库中的Event对象。 对象包含一个可由线程设置的信号标志,它允许线程等待某些事件的发生。在 初始情况下,Event对象中的信号标志被设置为假。如果有线程等待一个Event对象, 而这个Event对象的标志为假,那么这个线程将会被一直阻塞直至该标志为真。一个线程如果将一个Event对象的信号标志设置为真,它将唤醒所有等待这个Event对象的线程。如果一个线程等待一个已经被设置为真的Event对象,那么它将忽略这个事件, 继续执行 ‘‘‘

event.isSet():返回event的状态值; event.wait():如果 event.isSet()==False将阻塞线程; event.set(): 设置event的状态值为True,所有阻塞池的线程激活进入就绪状态, 等待操作系统调度; event.clear():恢复event的状态值为False。

可以考虑一种应用场景(仅仅作为说明),例如,我们有多个线程从Redis队列中读取数据来处理,这些线程都要尝试去连接Redis的服务,一般情况下,如果Redis连接不成功,在各个线程的代码中,都会去尝试重新连接。如果我们想要在启动时确保Redis服务正常,才让那些工作线程去连接Redis服务器,那么我们就可以采用threading.Event机制来协调各个工作线程的连接操作:主线程中会去尝试连接Redis服务,如果正常的话,触发事件,各工作线程会尝试连接Redis服务。 import threading import time import logging logging.basicConfig(level=logging.DEBUG, format=‘(%(threadName)-10s) %(message)s‘,) def worker(event): logging.debug(‘Waiting for redis ready...‘) event.wait() logging.debug(‘redis ready, and connect to redis server and do some work [%s]‘, time.ctime()) time.sleep(1) def main(): readis_ready = threading.Event() t1 = threading.Thread(target=worker, args=(readis_ready,), name=‘t1‘) t1.start() t2 = threading.Thread(target=worker, args=(readis_ready,), name=‘t2‘) t2.start() logging.debug(‘first of all, check redis server, make sure it is OK, and then trigger the redis ready event‘) time.sleep(3) # simulate the check progress readis_ready.set() if __name__=="__main__": main()

threading.Event的wait方法还接受一个超时参数,默认情况下如果事件一致没有发生,wait方法会一直阻塞下去,而加入这个超时参数之后,如果阻塞时间超过这个参数设定的值之后,wait方法会返回。对应于上面的应用场景,如果Redis服务器一致没有启动,我们希望子线程能够打印一些日志来不断地提醒我们当前没有一个可以连接的Redis服务,我们就可以通过设置这个超时参数来达成这样的目的:

def worker(event):

while not event.is_set():

logging.debug(‘Waiting for redis ready...‘)

event.wait(2)

logging.debug(‘redis ready, and connect to redis server and do some work [%s]‘, time.ctime())

time.sleep(1)

这样,我们就可以在等待Redis服务启动的同时,看到工作线程里正在等待的情况。

‘‘‘ Semaphore管理一个内置的计数器, 每当调用acquire()时内置计数器-1; 调用release() 时内置计数器+1; 计数器不能小于0;当计数器为0时,acquire()将阻塞线程直到其他线程调用release()。 实例:(同时只有5个线程可以获得semaphore,即可以限制最大连接数为5): ‘‘‘ import threading import time semaphore = threading.Semaphore(5) def func(): if semaphore.acquire(): print (threading.currentThread().getName() + ‘ get semaphore‘) time.sleep(2) semaphore.release() for i in range(20): t1 = threading.Thread(target=func) t1.start()

应用:连接池

思考:与Rlock的区别?(Rlock:多层嵌套,Semaphore:多个并列)

queue is especially useful in threaded programming when information must be exchanged safely between multiple threads.

‘‘‘ 创建一个“队列”对象 import queue q = queue.Queue(maxsize = 10) queue.Queue类即是一个队列的同步实现。队列长度可为无限或者有限。可通过Queue的构造函数的可选参数 maxsize来设定队列长度。如果maxsize小于1就表示队列长度无限。 将一个值放入队列中 q.put(10) 调用队列对象的put()方法在队尾插入一个项目。put()有两个参数,第一个item为必需的,为插入项目的值; 第二个block为可选参数,默认为 1。如果队列当前为空且block为1,put()方法就使调用线程暂停,直到空出一个数据单元。如果block为0, put方法将引发Full异常。 将一个值从队列中取出 q.get() 调用队列对象的get()方法从队头删除并返回一个项目。可选参数为block,默认为True。如果队列为空且 block为True,get()就使调用线程暂停,直至有项目可用。如果队列为空且block为False,队列将引发Empty异常。 ‘‘‘

‘‘‘ put 和 task_done 一一对应,表示所有曾加到队列中的任务,都执行完了,然后才能执行join之后的操作 ‘‘‘ ‘‘‘ join() 阻塞进程,直到所有任务完成,需要配合另一个方法task_done。 def join(self): with self.all_tasks_done: while self.unfinished_tasks: self.all_tasks_done.wait() task_done() 表示某个任务完成。每一条get语句后需要一条task_done。 import queue q = queue.Queue(5) q.put(10) q.put(20) print(q.get()) q.task_done() print(q.get()) q.task_done() q.join() print("ending!") ‘‘‘

‘‘‘ 此包中的常用方法(q = Queue.Queue()):

q.qsize() 返回队列的大小 q.empty() 如果队列为空,返回True,反之False q.full() 如果队列满了,返回True,反之False q.full 与 maxsize 大小对应 q.get([block[, timeout]]) 获取队列,timeout等待时间 q.get_nowait() 相当q.get(False)非阻塞

q.put(item) 写入队列,timeout等待时间 q.put_nowait(item) 相当q.put(item, False) q.task_done() 在完成一项工作之后,q.task_done() 函数向任务已经完成的队列发送一个信号 q.join() 实际上意味着等到队列为空,再执行别的操作 ‘‘‘

‘‘‘ Python Queue模块有三种队列及构造函数: 1、Python Queue模块的FIFO队列先进先出。 class queue.Queue(maxsize) 2、LIFO类似于堆,即先进后出。 class queue.LifoQueue(maxsize) 3、还有一种是优先级队列级别越低越先出来。 class queue.PriorityQueue(maxsize) ‘‘‘

import queue #先进后出 q=queue.LifoQueue() q.put(34) q.put(56) q.put(12) #优先级 q=queue.PriorityQueue() q.put([5,100]) q.put([7,200]) q.put([3,"hello"]) q.put([4,{"name":"alex"}]) while 1: data=q.get() print(data)

在线程世界里,生产者就是生产数据的线程,消费者就是消费数据的线程。在多线程开发当中,如果生产者处理速度很快,而消费者处理速度很慢,那么生产者就必须等待消费者处理完,才能继续生产数据。同样的道理,如果消费者的处理能力大于生产者,那么消费者就必须等待生产者。为了解决这个问题于是引入了生产者和消费者模式。

生产者消费者模式是通过一个容器来解决生产者和消费者的强耦合问题。生产者和消费者彼此之间不直接通讯,而通过阻塞队列来进行通讯,所以生产者生产完数据之后不用等待消费者处理,直接扔给阻塞队列,消费者不找生产者要数据,而是直接从阻塞队列里取,阻塞队列就相当于一个缓冲区,平衡了生产者和消费者的处理能力。

这就像,在餐厅,厨师做好菜,不需要直接和客户交流,而是交给前台,而客户去饭菜也不需要不找厨师,直接去前台领取即可,这也是一个结耦的过程。

import time,random import queue,threading q = queue.Queue() def Producer(name): count = 0 while count <10: print("making........") time.sleep(random.randrange(3)) q.put(count) print(‘Producer %s has produced %s baozi..‘ %(name, count)) count +=1 #q.task_done() #q.join() print("ok......") def Consumer(name): count = 0 while count <10: time.sleep(random.randrange(4)) if not q.empty(): data = q.get() #q.task_done() #q.join() print(data) print(‘\033[32;1mConsumer %s has eat %s baozi...\033[0m‘ %(name, data)) else: print("-----no baozi anymore----") count +=1 p1 = threading.Thread(target=Producer, args=(‘A‘,)) c1 = threading.Thread(target=Consumer, args=(‘B‘,)) # c2 = threading.Thread(target=Consumer, args=(‘C‘,)) # c3 = threading.Thread(target=Consumer, args=(‘D‘,)) p1.start() c1.start() # c2.start() # c3.start()

‘‘‘ Multiprocessing is a package that supports spawning processes using an API similar to the threading module. The multiprocessing package offers both local and remote concurrency,effectively side-stepping the Global Interpreter Lock by using subprocesses instead of threads. Due to this, the multiprocessing module allows the programmer to fully leverage multiple processors on a given machine. It runs on both Unix and Windows. 由于GIL的存在,python中的多线程其实并不是真正的多线程,如果想要充分地使用多核CPU的资源,在python中大部分情况需要使用多进程。 multiprocessing包是Python中的多进程管理包。与threading.Thread类似,它可以利用multiprocessing.Process对象来创建一个进程。该进程可以运行在Python程序内部编写的函数。该Process对象与Thread对象的用法相同,也有start(), run(), join()的方法。此外multiprocessing包中也有Lock/Event/Semaphore/Condition类 (这些对象可以像多线程那样,通过参数传递给各个进程),用以同步进程,其用法与threading包中的同名类一致。所以,multiprocessing的很大一部份与threading使用同一套API,只不过换到了多进程的情境。 ‘‘‘

# Process类调用 from multiprocessing import Process import time def f(name): print(‘hello‘, name,time.ctime()) time.sleep(1) if __name__ == ‘__main__‘: p_list=[] for i in range(3): p = Process(target=f, args=(‘alvin:%s‘%i,)) p_list.append(p) p.start() for i in p_list: p.join() print(‘end‘) # 继承Process类调用 from multiprocessing import Process import time class MyProcess(Process): def __init__(self): super(MyProcess, self).__init__() # self.name = name def run(self): print (‘hello‘, self.name,time.ctime()) time.sleep(1) if __name__ == ‘__main__‘: p_list=[] for i in range(3): p = MyProcess() p.start() p_list.append(p) for p in p_list: p.join() print(‘end‘)

需要写在 if __name__ == ‘__main__‘: 内

构造方法:

Process([group [, target [, name [, args [, kwargs]]]]])

group: 线程组,目前还没有实现,库引用中提示必须是None;

target: 要执行的方法;

name: 进程名;

args/kwargs: 要传入方法的参数。

实例方法:

is_alive():返回进程是否在运行。

join([timeout]):阻塞当前上下文环境的进程程,直到调用此方法的进程终止或到达指定的timeout(可选参数)。

start():进程准备就绪,等待CPU调度

run():strat()调用run方法,如果实例进程时未制定传入target,这star执行t默认run()方法。

terminate():不管任务是否完成,立即停止工作进程

属性:

daemon:和线程的setDeamon功能一样

name:进程名字。

pid:进程号。

from multiprocessing import Process import os import time def info(name): print("name:",name) print(‘parent process:‘, os.getppid()) print(‘process id:‘, os.getpid()) print("------------------") time.sleep(1) def foo(name): info(name) if __name__ == ‘__main__‘: info(‘main process line‘) p1 = Process(target=info, args=(‘alvin‘,)) p2 = Process(target=foo, args=(‘egon‘,)) p1.start() p2.start() p1.join() p2.join() print("ending")

标签:共享 指令 产品 通过 make time orm ogr ctime

原文地址:http://www.cnblogs.com/zihe/p/7200923.html