标签:http exit 就是 控制 wan 一个 \n join() bubuko

线程一般是以并发方式执行的,正是由于这种并发和数据共享机制,使得多任务之间的协作成为可能。但是,在单核cpu中,真正的并发是不可能的,所以多线程的执行实际上是这样的:每个线程运行一会,然后让步给其余的线程,在某个时间点只有一个线程执行。因为上下文的切换时间很快,因此对用户来说就是类似的多并发执行。python的并发就是采用的这种执行效果。

因为线程之间共享同一片数据空间,可能会存在两个或多个线程对同一个数据进行运算的情况,这样就会导致运算结果不一致的情况,这种情况称为竟态条件。可以使用锁来解决这样的问题。

python代码的执行是由python虚拟机进行控制的。python在设计时是这样考虑的,在主循环中同时只能有一个控制线程在执行,就像单核cpu系统中的多进程一样。内存中可以有很多程序,但是在任意给定的时刻只能有一个程序在运行。

对python虚拟机的访问是由全局解释器锁GIL控制的,这个锁用来保证同事只能有一个线程运行。在多线程环境中,python虚拟机将按照下面所述的方式执行。

python2.x中虽然有thread和threading两个模块,但推荐使用threading模块,并且在python3.x中只有threading模块,因此这里只说明threading模块的用法。

在使用threading模块中thread类来启动多线程时,可以使用以下三种方法:

经常使用的第一个或者第三个

第一种:

import threading from time import sleep, ctime loops = [4,2] def loop(nloop, nsec): print "start loop", nloop, "at:", ctime() sleep(nsec) print "loop", nloop, "done at:", ctime() def main(): print ‘starting at:‘, ctime() threads = [] nloops = range(len(loops)) for i in nloops: t = threading.Thread(target=loop, args=(i,loops[i])) threads.append(t) for i in nloops: threads[i].start() # for i in nloops: # 注意有无join的区别 # threads[i].join() print "all Done at:" , ctime() if __name__ == "__main__": main()

上述代码中利用threading模块的Thread类开启了两个线程,然后把开启的线程放入列表中,循环列表开始执行每一个线程。其中使用了join()方法,join的作用是等待所有的子线程完成之后,再继续执行主函数。可以对join代码进行注释以测试join函数的作用。

第二种:

import threading from time import ctime, sleep loops = [4,2] class MyThread(object): def __init__(self, func, args, name = "",): self.name = name self.func = func self.args = args def __call__(self): self.func(*self.args) def loop(nloop, nsec): print "start loop", nloop, "at:", ctime() sleep(nsec) print "loop", nloop, "done at:", ctime() def main(): print("starting at: ", ctime()) threads = [] nloops = range(len(loops)) for i in nloops: t = threading.Thread(target=MyThread(loop, (i, loops[i]), loop.__name__)) # 创建Thread类实例,然后把要传入的函数及参数封装成一个类实例传入。注意创建的类需调用内置的__call__方法。 # 注意内置__call__方法怎么调用 # A = class(object): # def __call__(self): # print("call") # a = A() # a() # 调用内置call方法 threads.append(t) for i in nloops: threads[i].start() for i in nloops: threads[i].join() print("all done!", ctime()) main()

注意:这里在实例化Thread对象时,同事实例化了自己创建的MyThread类,因此这里实际上完成了两次实例化。

注意:__call__函数的调用,在代码中已经给出调用的方法。

第三种:

import threading from time import ctime, sleep loops = [4,2] class MyThread(threading.Thread): def __init__(self, func, args, name = "",): super(MyThread,self).__init__() self.name = name self.func = func self.args = args def run(self): self.func(*self.args) def loop(nloop, nsec): print "start loop", nloop, "at:", ctime() sleep(nsec) print "loop", nloop, "done at:", ctime() def main(): print("starting at: ", ctime()) threads = [] nloops = range(len(loops)) for i in nloops: t = MyThread(loop, (i, loops[i]), loop.__name__) threads.append(t) for i in nloops: threads[i].start() for i in nloops: threads[i].join() print("all done!", ctime()) main()

注意:

import time import threading def run(n): print(‘[%s]------running----\n‘ % n) time.sleep(2) print(‘--done--‘) def main(): for i in range(5): t = threading.Thread(target=run, args=[i, ]) t.start() t.join(1) print(‘starting thread‘, t.getName()) m = threading.Thread(target=main, args=[]) # m.setDaemon(True) # 将main线程设置为Daemon线程,它做为程序主线程的守护线程,当主线程退出时,m线程也会退出,由m启动的其它子线程会同时退出,不管是否执行完任务 m.start() m.join(timeout=2) print("---main thread done----")

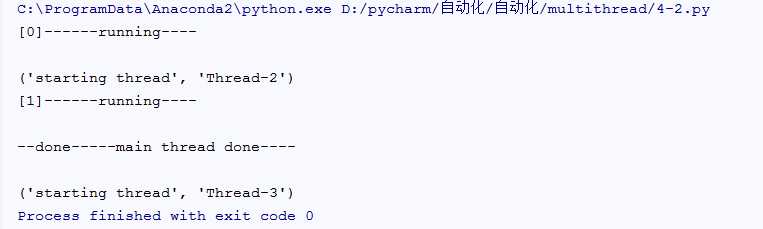

解释:在没有设置守护线程时,主线程退出时,开辟的子线程仍然会执行;若设置为守护进程,则在子线程退出是,对应的子线程会直接退出。

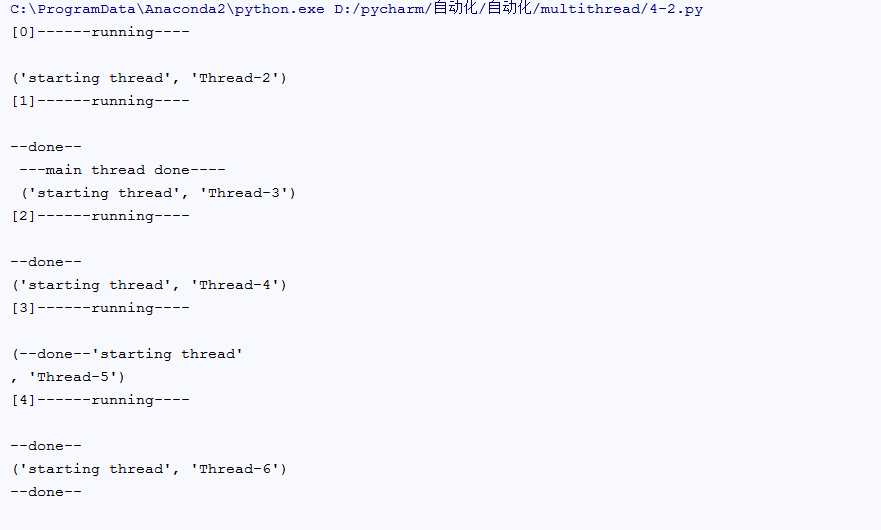

没有设置守护线程结果如下:

设置守护线程执行结果如下:

# *-* coding:utf-8 *-* # Auth: wangxz from MyThread import MyThread from time import ctime, sleep def fib(x): sleep(0.005) if x < 2: return 1 return (fib(x - 2) + fib(x - 1)) def fac(x): sleep(0.05) if x < 2: return 1 return (x * fac(x - 1)) def sum(x): sleep(0.05) if x < 2: return 1 return (x + sum(x - 1 )) func = [fib, fac, sum] n = 12 def main(): nfunc = range(len(func)) print("single thread".center(50,"-")) for i in nfunc: print("The %s starting at %s" % (func[i].__name__, ctime())) print(func[i](n)) print("The %s stop at %s" % (func[i].__name__, ctime())) print("Multiple threads".center(50,"-")) threads = [] for i in nfunc: t = MyThread(func[i],(n,),func[i].__name__) threads.append(t) for i in nfunc: threads[i].start() for i in nfunc: threads[i].join() print(threads[i].getResult()) print("all Done!") main()

注意:因为执行太快因此在程序中加入的sleep函数,减慢执行的速度。

在之前我们提到过多个线程之间,共享一段内存空间,因此当多个线程同时修改内存空间中的某个数值的时候,可能会出现不能达到预期效果的情况。针对这种情况,我们可以使用threading模块中的锁来控制线程的修改。

python的多线程适合用于IO密集型的任务当中,而不适合CPU密集型。其中IO操作不占用CPU,而计算占用CPU。

python对于计算密集型的任务开多线程的效率甚至不如串行(没有大量切换),但是,对于IO密集型的任务效率还是有显著提升的。

多线程中锁的争用问题,https://www.cnblogs.com/lidagen/p/7237674.html

#!/usr/bin/env python #*-* coding:utf-8 *-* import threading, time a = 50 b = 50 c = 50 d = 50 def printvars(): print "a = ", a print "b = ", b print "c = ", c print "d = ", d def threadcode(): global a, b, c, d a += 50 time.sleep(0.01) b = b + 50 c = 100 d = "Hello" print "[ChildThread] values of variabled in child thread:" printvars() print "[Mainchild] values of variables before child thread:" printvars() #create new thread t = threading.Thread(target = threadcode, name = "childThread") #This thread won‘t keep the program from terminating. t.setDaemon(1) #start the new thread t.start() #wait for the child thread to exit. t.join() print "[MainThread] values of variables after child thread:" printvars()

程序开始的时候定义了4个变量。他们的值都是50,显示这些值,然后建立一个线程,线程使用不同的方法改变每个变量,输出变量,然后终止。主线程接着在join()和再次打印出值后取得控制权。主线程没有修改这些值。

函数执行结果如下:

[Mainchild] values of variables before child thread:

a = 50

b = 50

c = 50

d = 50

[ChildThread] values of variabled in child thread:

a = 100

b = 100

c = 100

d = Hello

[MainThread] values of variables after child thread:

a = 100

b = 100

c = 100

d = Hello

分析:如果两个不同的线程同时给50加b,那么结果就会有以下两种情况。

为了防止这种争用的现象,引入了锁的概念。

python的threading模块提供了一个Lock对象。这个对象可以被用来同步访问代码。Lock对象有两个方法,acquire()和release()。acquire()方法负责取得一个锁,如果没有线程正持有锁,acquire()方法会立刻得到锁,否则,它需要等到锁被释放。

release()会释放一个锁,如果有其他的线程正等待这个锁(通过acquire),当release释放的时候,他们中的一个线程就会被唤醒,也就是说,某个线程中的acquire()将会被调用。

实例如下:

#!/usr/bin/env python #*-* coding:utf-8 *-* import threading, time #Initialize a aimple variable b = 50 #And a lock object l = threading.Lock() def threadcode(): """This is run in the created threads""" global b print "Thread %s invoked" % threading.currentThread().getName() # Acquire the lock (will not return until a lock is acquired) l.acquire() try: print "Thread %s running" % threading.currentThread().getName() time.sleep(1) b = b + 50 print "Thread %s set b to %d" % (threading.currentThread().getName(),b) finally: l.release() print "Value of b at start of program:", b childthreads = [] for i in xrange(1, 5): # create new thread t = threading.Thread(target = threadcode, name = "Thread-%d" % i) #This thread won‘t keep the program from terminating t.setDaemon(1) #Start the new thread t.start() childthreads.append(t) for t in childthreads: #wait for the child thread to exit: t.join() print "New value of b:", b -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Value of b at start of program: 50 Thread Thread-1 invoked Thread Thread-1 running Thread Thread-2 invoked Thread Thread-3 invoked Thread Thread-4 invoked Thread Thread-1 set b to 100 Thread Thread-2 running Thread Thread-2 set b to 150 Thread Thread-3 running Thread Thread-3 set b to 200 Thread Thread-4 running Thread Thread-4 set b to 250 New value of b: 250

以上加的需要等到阻塞的锁,也可以称为互斥锁。

实例:之前看到过一片博文,但是把博文地址忘了,博文中的实例大概如下:

#!/usr/bin/env python import threading import time a = 1 def addNum(): global a b = a time.sleep(0.001) # 记得这里是用停顿,模拟大量的IO操作 a = b + 1 time.sleep(1) threads = [] for i in range(100): t = threading.Thread(target=addNum) t.start() threads.append(t) for t in threads: t.join() -----------执行--------------- [root@ct02 ~]# python one.py The end num is 9 [root@ct02 ~]# python one.py The end num is 11 [root@ct02 ~]# python one.py The end num is 10 [root@ct02 ~]# python one.py The end num is 11

然后加入锁之后:

cat one.py #!/usr/bin/env python import threading import time a = 1 def addNum(): global a lock.acquire() b = a time.sleep(0.001) a = b + 1 lock.release() time.sleep(1) threads = [] lock = threading.Lock() for i in range(100): t = threading.Thread(target=addNum) t.start() threads.append(t) for t in threads: t.join() print "The end num is %s" % a

可以参考博文:https://blog.csdn.net/u013210620/article/details/78723704

如果一个线程想不止一次访问某一共享资源,可能就会发生死锁现象。第一个acquire没有释放,第二次的acquire就继续请求。

#!/usr/bin/env python #*-* coding:utf-8 *-* import threading import time def foo(): lockA.acquire() print "foo获得A锁" lockB.acquire() print "foo获得B锁" lockB.release() lockA.release() def bar(): lockB.acquire() print "bar获得A锁" time.sleep(2) # 模拟io或者其他操作,第一个线程执行到这,在这个时候,lockA会被第二个进程占用 # 所以第一个进程无法进行后续操作,只能等待lockA锁的释放 lockA.acquire() print "bar获得B锁" lockB.release() lockA.release() def run(): foo() bar() lockA=threading.Lock() lockB=threading.Lock() for i in range(10): t=threading.Thread(target=run,args=()) t.start() 输出结果:只有四行,因为产生了死锁阻断了 foo获得A锁 foo获得B锁 bar获得A锁 foo获得A锁

第一个线程(系统中产生的第一个)获得A锁,获得B锁,因此会执行foo函数,然后释放得到的锁。接着执行bar函数,获得B锁(未释放),执行 print "bar获得A锁"语句,然后进入等待;第二个线程执行foo函数,获得A锁,但获得B锁时候需要等待。

#!/usr/bin/env python #coding:utf-8 from threading import Thread,Lock,RLock import time mutexA=mutexB=RLock() # 注意只能这样连等的生成锁对象 class MyThread(Thread): def run(self): self.f1() self.f2() def f1(self): mutexA.acquire() print(‘%s 拿到A锁‘ %self.name) mutexB.acquire() print(‘%s 拿到B锁‘ %self.name) mutexB.release() mutexA.release() def f2(self): mutexB.acquire() print(‘%s 拿到B锁‘ % self.name) time.sleep(0.1) mutexA.acquire() print(‘%s 拿到A锁‘ % self.name) mutexA.release() mutexB.release() if __name__ == ‘__main__‘: for i in range(5): t=MyThread() t.start()

信号量是python的一个内置计数器。

每当调用acquire()时,内置计数器-1, 每当调用release()时,内置计数器+1,计数器不能小于0,当计数器为0时,acquire()将阻塞线程直到其他线程调用release()。

如果不加入计数,代码如下:#!/usr/bin/env python #coding:utf-8 import threading, time def hello(): print "Hello wolrd at %s" % time.ctime() time.sleep(2) for i in range(12): t = threading.Thread(target=hello) t.start() -------------执行----------------- Hello wolrd at Mon May 28 11:46:18 2018 Hello wolrd at Mon May 28 11:46:18 2018 Hello wolrd at Mon May 28 11:46:18 2018 Hello wolrd at Mon May 28 11:46:18 2018 Hello wolrd at Mon May 28 11:46:18 2018 Hello wolrd at Mon May 28 11:46:18 2018 Hello wolrd at Mon May 28 11:46:18 2018 Hello wolrd at Mon May 28 11:46:18 2018 Hello wolrd at Mon May 28 11:46:18 2018 Hello wolrd at Mon May 28 11:46:18 2018 Hello wolrd at Mon May 28 11:46:18 2018 Hello wolrd at Mon May 28 11:46:18 2018

加入计数,代码执行如下:

#!/usr/bin/env python #coding:utf-8 import threading, time sem = threading.BoundedSemaphore(3) # 加入计数 def hello(): sem.acquire() print "Hello wolrd at %s" % time.ctime() time.sleep(2) sem.release() for i in range(12): t = threading.Thread(target=hello) t.start() ---------------------执行----------------------- Hello wolrd at Mon May 28 11:48:12 2018 Hello wolrd at Mon May 28 11:48:12 2018 Hello wolrd at Mon May 28 11:48:12 2018 Hello wolrd at Mon May 28 11:48:14 2018 Hello wolrd at Mon May 28 11:48:14 2018 Hello wolrd at Mon May 28 11:48:14 2018 Hello wolrd at Mon May 28 11:48:16 2018 Hello wolrd at Mon May 28 11:48:16 2018 Hello wolrd at Mon May 28 11:48:16 2018 Hello wolrd at Mon May 28 11:48:18 2018 Hello wolrd at Mon May 28 11:48:18 2018 Hello wolrd at Mon May 28 11:48:18 2018 # 每次最多有三个线程执行,防止线程产生过多阻塞操作系统

多久之后执行代码:

#!/usr/bin/env python #coding:utf-8 import threading, time def hello(): print "Hello wolrd at %s" % time.ctime() time.sleep(2) t = threading.Timer(5.0, hello) # 5s之后执行hello函数 print "before starting %s" % time.ctime() t.start() ----------------------执行---------------------- before starting Mon May 28 11:52:14 2018 Hello wolrd at Mon May 28 11:52:19 2018

上面所有的实例,都是各个线程独自运行。下面,我们考虑两个线程之间的交互。

threading.Event机制类似于一个线程向其它多个线程发号施令的模式,其它线程都会持有一个threading.Event的对象,这些线程都会等待这个事件的“发生”,如果此事件一直不发生,那么这些线程将会阻塞,直至事件的“发生”。

一个线程之间通信的实例:

import threading import time event = threading.Event() def lighter(): count = 0 while True: if count < 5: event.set() print("\033[32;1m The green running...\033[0m") elif count > 4 and count < 10: event.clear() print("\033[31;1m the red light is lighting \033[0m") else: count = 0 print("\033[32;1m The green running...\033[0m") count += 1 # print(count) time.sleep(1) def cars(name): while True: if event.is_set(): print("\033[36;1m The car %s is running fast\033[0m" % name) else: print("\033[36;1m The car %s is waiting..\033[0m" % name) time.sleep(0.5) threads = [] for i in range(3): car = threading.Thread(target=cars, args=("Tesla_%s" % i,)) threads.append(car) t1 = threading.Thread(target=lighter) t1.start() for i in range(len(threads)): threads[i].start()

queue是python标准库中的线程安全的队列(FIFO)实现,提供了一个适用于多线程编程的先进先出的数据结构,即队列,用来在生产者和消费者线程之间的信息传递

基于queue有三种基本的队列:

意味着之前入队的一个任务已经完成。由队列的消费者线程调用。每一个get()调用得到一个任务,接下来的task_done()调用告诉队列该任务已经处理完毕。

如果当前一个join()正在阻塞,它将在队列中的所有任务都处理完时恢复执行(即每一个由put()调用入队的任务都有一个对应的task_done()调用)。

用于表示队列中的某个元素已经执行完成,该方法会被join使用。

阻塞调用线程,直到队列中的所有任务被处理掉。

只要有数据被加入队列,未完成的任务数就会增加。当消费者线程调用task_done()(意味着有消费者取得任务并完成任务),未完成的任务数就会减少。当未完成的任务数降到0,join()解除阻塞。

在队列中的所有元素执行完毕,并调用task_done之前保持阻塞。

将item放入队列中。

put_nowait等同于put(item, False)从队列中移除并返回一个数据。block跟timeout参数同put方法

其非阻塞方法为`get_nowait()`相当与get(False)

如果队列为空,返回True,反之返回False.

在并发编程中使用生产者和消费者模式能够解决绝大多数并发问题。该模式通过平衡生产线程和消费线程的工作能力来提高程序的整体处理数据的速度。

为什么要使用生产者和消费者模式

在线程世界里,生产者就是生产数据的线程,消费者就是消费数据的线程。在多线程开发当中,如果生产者处理速度很快,而消费者处理速度很慢,那么生产者就必须等待消费者处理完,才能继续生产数据。同样的道理,如果消费者的处理能力大于生产者,那么消费者就必须等待生产者。为了解决这个问题于是引入了生产者和消费者模式。

什么是生产者消费者模式

生产者消费者模式是通过一个容器来解决生产者和消费者的强耦合问题。生产者和消费者彼此之间不直接通讯,而通过阻塞队列来进行通讯,所以生产者生产完数据之后不用等待消费者处理,直接扔给阻塞队列,消费者不找生产者要数据,而是直接从阻塞队列里取,阻塞队列就相当于一个缓冲区,平衡了生产者和消费者的处理能力。

一个简单的生产者消费者模型队列:

import threading from time import ctime, sleep import queue store_q = queue.Queue() def productor(num): while True: print("\033[32;1mStarting create the gold at %s\033[0m" % ctime()) store_q.put(("gold", num)) print("has stored the gold") sleep(1) def consum(): while True: if store_q.qsize() > 0: print("Start to sail the gold") store_q.get() print("\033[31;1mHas sailed the gold\033[0m") else: print("Waiting the gold....") sleep(0.8) t1 = threading.Thread(target=productor,args=(1,)) t2 = threading.Thread(target=consum) t1.start() t2.start()

先pass,随后会附上自己写的线程池博文连接。

标签:http exit 就是 控制 wan 一个 \n join() bubuko

原文地址:https://www.cnblogs.com/wxzhe/p/9078226.html