标签:start min thread ocs png rbo 标准 标准库 结束

本文希望达到的目标:

一、多线程的基本认识

多线程编程的目的:并行处理子任务,大幅度地提升整个任务的效率。

同一个进程中的线程,共享相同的运行环境,共享同一片数据空间,所以线程间的通讯笔进程间的通信更简单,但是这样的共享是会有危险的,如果多线程共同访问同一数据,因为访问顺序的不同,可能会导致结果不一致。

二、多线程编程的模块和类的使用

为了更好说明多线程的优点以及多个标准库使用的差异性,以模拟“一个程序完成2个独立任务时间总和”为例子。

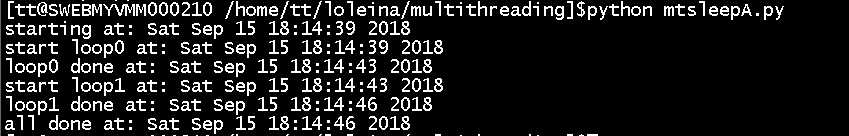

0、单进程单线程运行两个独立的任务:顺序执行,完成第一个任务后,再完成第二个任务。总时间是各个循环 运行时间之和,实际两个任务是完全独立的,如果并行执行,是可以减少运行时间的。

import thread

from time import sleep,ctime

def loop0():

print ‘start loop0‘,‘at:‘,ctime()

sleep(4)

print ‘loop0‘,‘done at:‘,ctime()

def loop1():

print ‘start loop1‘,‘at:‘,ctime()

sleep(3)

print ‘loop1‘,‘done at:‘,ctime()

def main():

print ‘starting at:‘,ctime()

loop0()

loop1()

print ‘all done at:‘,ctime()

if __name__==‘__main__‘:

main()

1、thread模块

python提供了两个标准库用于多线程编程,thread模块提供了基本的线程和锁的支持,而 threading 提供了更高级别,功能更强的线程管理的功能。一般都建议使用threading模块,毕竟功能更强大,更好管理。

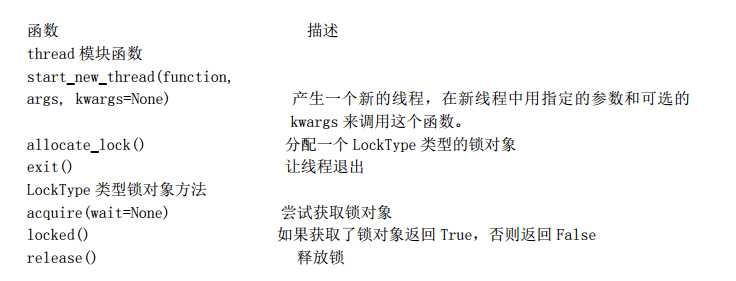

thread模块和对象:(官网:https://docs.python.org/2/library/thread.html)

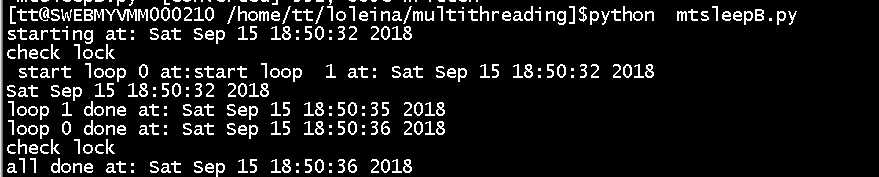

使用多线程编程,创建两个线程同时执行两个独立的任务,需要考虑,主线程执行时间和子线程执行时间的关系,如果单纯的创建线程去运行这2个任务,主线程执行完成时间必然比子线程快,子线程未运行完,主线程就已经退出了,在thread模块使用锁对象lock来管理,为每个线程创建一个锁对象,在线程执行完成后释放锁,而主线程判断所有的锁都释放后才能结束,进程间的通讯机制就这样简单的建立起来。

import thread from time import sleep,ctime loops =[4,3] def loop(nloop,nsec,lock): print ‘start loop‘,nloop,‘at:‘,ctime() sleep(nsec) print ‘loop‘,nloop,‘done at:‘,ctime() lock.release() def main(): print ‘starting at:‘,ctime() locks = [] nloops = range(len(loops)) for i in nloops: lock = thread.allocate_lock() lock.acquire() locks.append(lock) for i in nloops: thread.start_new_thread(loop,(i,loops[i],locks[i])) for i in nloops: print ‘check lock‘ while locks[i].locked(): pass print ‘all done at:‘,ctime() if __name__==‘__main__‘: main()

运行时间为4s,单进程耗时7s,运行时间有减少。为什么不在创建锁的循环里创建线程呢?有以下几个原因:(1) 我 们想到实现线程的同步,所以要让“所有的马同时冲出栅栏”。(2) 获取锁要花一些时间,如果线程退出得“太快”,可能会导致还没有获得锁,线程就已经结束了的情况。

注意:

A:子线程开始:创建对象调用start_new_thread函数时,该函数不是在主线程里运行, 而是产生一个新的线程来运行这个函数。一旦调用该函数,子线程已经开始运行。

B:子线程退出:它不支持守护线程。当主线程退出时,所有的子线程不论它们是否还在工作,都会被强行退出。

2、threading模块 :创建一个 Thread 的实例,传给它一个函数

它不仅提供了 Thread 类,还提供了各 种非常好用的同步机制。

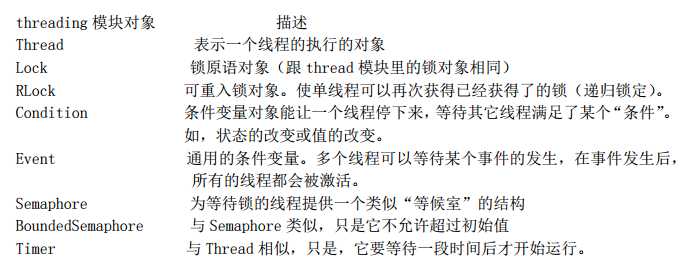

threading模块和对象:(官网:https://docs.python.org/2/library/threading.html)

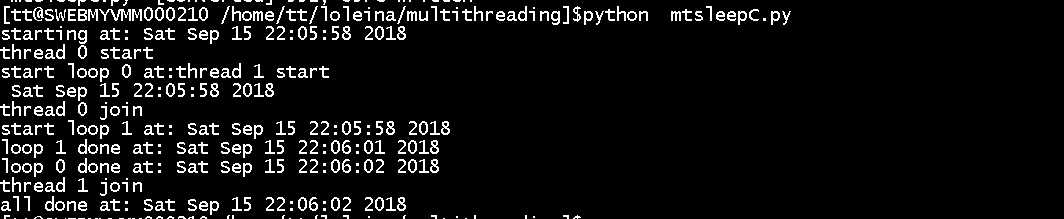

import threading from time import sleep,ctime loops =[4,3] def loop(nloop,nsec): print ‘start loop‘,nloop,‘at:‘,ctime() sleep(nsec) print ‘loop‘,nloop,‘done at:‘,ctime() def main(): print ‘starting at:‘,ctime() threads = [] nloops = range(len(loops)) for i in nloops: t = threading.Thread(target=loop,args=(i,loops[i])) threads.append(t) for i in nloops: print ‘thread‘,i,‘start‘ threads[i].start() for i in nloops: print ‘thread‘,i,‘join‘ threads[i].join() print ‘all done at:‘,ctime() if __name__==‘__main__‘: main()

注意:

A、子线程开始:调用start函数。所有的线程都创建了之后,再一起调用 start()函数启动,而不是创建一个启动一个。而且, 不用再管理一堆锁(分配锁,获得锁,释放锁,检查锁的状态等)

B、子线程结束:可以控制子线程和主线程结束的顺序,调用join(timeout=None) 程序挂起,直到线程结束;

C、守护线程一般是一个等待客户请求的服务器, 如果没有客户提出请求,它就在那等着。如果设定一个线程为守护线程,就表示这个线程 是不重要的,在进程退出的时候,不用等待这个线程退出。

3、thread类 :Thread 派生出一个子类,创建一个这个子类的实例

import threading from time import sleep,ctime loops =(4,3) class MyThread(threading.Thread): def __init__(self,func,args,name=‘‘): threading.Thread.__init__(self) self.name = name self.func = func self.args = args def run(self): self.func(*self.args) def loop(nloop,nsec): print ‘start loop‘,nloop,‘at:‘,ctime() sleep(nsec) print ‘loop‘,nloop,‘done at:‘,ctime() def main(): print ‘starting at:‘,ctime() threads = [] nloops = range(len(loops)) for i in nloops: t = MyThread(loop,(i,loops[i]),loop.__name__) threads.append(t) for i in nloops: print ‘thread‘,i,‘start‘ threads[i].start() for i in nloops: print ‘thread‘,i,‘join‘ threads[i].join() print ‘all done at:‘,ctime() if __name__==‘__main__‘: main()

4、threading模块中的thread类部分源码解析

thread模块提供了一系列基础函数,其实不是不能用,书本上写着的是不建议使用,但是如果用于底层开发是可以的。threading模块与之相比,最大的不同就是,threading模块中的thread类的属性特别多,

包含了对多线程的各自管理上的纬度属性,所以特别方便使用,实际上threading模块就是在thread模块上开发的,做了进一步的集成化和封装以便于用户更轻便的管理。

A :threadding模块有引用thread模块:

try: import thread except ImportError: del _sys.modules[__name__] raise

B: thread类的初始化函数部分截图如下:初始化的过程,其实就是多线程的属性的初始化的过程。把其中需要的资源,入参,thread管理的各自对象都初始化。

def __init__(self, group=None, target=None, name=None, args=(), kwargs=None, verbose=None): assert group is None, "group argument must be None for now" _Verbose.__init__(self, verbose) if kwargs is None: kwargs = {} self.__target = target self.__name = str(name or _newname()) self.__args = args self.__kwargs = kwargs self.__daemonic = self._set_daemon() self.__ident = None self.__started = Event() self.__stopped = False self.__block = Condition(Lock()) self.__initialized = True # sys.stderr is not stored in the class like # sys.exc_info since it can be changed between instances self.__stderr = _sys.stderr

C:thread类的start函数,看到调用底层的_start_new_thread函数,就明白了,为啥thread类是调用start函数来启动线程,还调用了self.__started.wait(),__started对象实际是_Condition类的实例,这是一个对

线程锁管理的实例,调用这个类的wait方法就是在获取一把锁。

def start(self): if not self.__initialized: raise RuntimeError("thread.__init__() not called") if self.__started.is_set(): raise RuntimeError("threads can only be started once") if __debug__: self._note("%s.start(): starting thread", self) with _active_limbo_lock: _limbo[self] = self try: _start_new_thread(self.__bootstrap, ()) except Exception: with _active_limbo_lock: del _limbo[self] raise self.__started.wait()

def wait(self, timeout=None): if not self._is_owned(): raise RuntimeError("cannot wait on un-acquired lock") waiter = _allocate_lock() waiter.acquire() self.__waiters.append(waiter) saved_state = self._release_save() try: # restore state no matter what (e.g., KeyboardInterrupt) if timeout is None: waiter.acquire() if __debug__: self._note("%s.wait(): got it", self) else: # Balancing act: We can‘t afford a pure busy loop, so we # have to sleep; but if we sleep the whole timeout time, # we‘ll be unresponsive. The scheme here sleeps very # little at first, longer as time goes on, but never longer # than 20 times per second (or the timeout time remaining). endtime = _time() + timeout delay = 0.0005 # 500 us -> initial delay of 1 ms while True: gotit = waiter.acquire(0) if gotit: break remaining = endtime - _time() if remaining <= 0: break delay = min(delay * 2, remaining, .05) _sleep(delay) if not gotit: if __debug__: self._note("%s.wait(%s): timed out", self, timeout) try: self.__waiters.remove(waiter) except ValueError: pass else: if __debug__: self._note("%s.wait(%s): got it", self, timeout) finally: self._acquire_restore(saved_state)

D:而调用join方法,实际也是调用_Condition类的实例,判断当前锁的状态,在线程运行完毕后,释放锁。

def join(self, timeout=None): if not self.__initialized: raise RuntimeError("Thread.__init__() not called") if not self.__started.is_set(): raise RuntimeError("cannot join thread before it is started") if self is current_thread(): raise RuntimeError("cannot join current thread") if __debug__: if not self.__stopped: self._note("%s.join(): waiting until thread stops", self) self.__block.acquire() try: if timeout is None: while not self.__stopped: self.__block.wait() if __debug__: self._note("%s.join(): thread stopped", self) else: deadline = _time() + timeout while not self.__stopped: delay = deadline - _time() if delay <= 0: if __debug__: self._note("%s.join(): timed out", self) break self.__block.wait(delay) else: if __debug__: self._note("%s.join(): thread stopped", self) finally: self.__block.release()

三、Cpython的全局解释器锁GIL

推荐一篇更全面介绍的博客:https://www.cnblogs.com/frchen/p/5740606.html

GIL全称 Global Interpreter Lock, 这个问题。像单 CPU 的系统中运行多个进程那样,内存中可以存放多个程序,但任意时刻,只有一个程序在 CPU 中运行。 在CPython 解释器中可以“运行” 多个线程,但在任意时刻,只有一个线程在解释器中运行。而对 Python 虚拟机的访问由全局解释器锁(GIL)来控制,正是这个锁能保证同一时刻只有一个线程在运行。GIL 并不是Python的特性,它是在实现Python解析器(CPython)时所引入的一个概念。实际现在一般使用的解析器都是基于CPython的,如果是Jpython(基于java),可能就不存在

对所有面向 I/O 的(会调用内建的操作系统 C 代码的)程序来说,GIL 会在这个 I/O 调用之前被释放,以允许其它的线程在这个线程等待 I/O 的时候运行。如果某线程并未使用很多 I/O 操作, 它会在自己的时间片内一直占用处理器(和 GIL)。也就是说,I/O 密集型的 Python 程序比计算密集型的程序更能充分利用多线程环境的好处。

简单的总结下就是:Python的多线程在多核CPU上,只对于IO密集型计算产生积极效果;而当有至少有一个CPU密集型线程存在,那么多线程效率会由于GIL而大幅下降。

标签:start min thread ocs png rbo 标准 标准库 结束

原文地址:https://www.cnblogs.com/loleina/p/9651478.html