标签:initial error doc 情况下 elements nis tst 不可 rac

目录

使用Boost.Python构建混合系统

Author: David Abrahams

Contact: dave@boost-consulting.com

Organization: Boost Consulting

Date: 2003-05-14

Author: Ralf W. Grosse-Kunstleve

Copyright: Copyright David Abrahams and Ralf W. Grosse-Kunstleve 2003. All rights reserved

目录

Boost.Python是一个开源C++库,它提供了一个类似IDL的简洁接口,用于将C++类和函数绑定到Python。利用C++编译自省功能和元编程技术,Boost.Python完全用纯C++实现的,不需要引入新的语法。Boost.Python丰富的特性集和高级接口使它能够作为混合系统从底层开始设计包,从而使程序员能够轻松一致地访问高效的C++编译时多态性和极其方便的Python运行时多态性。

Boost.Python is an open source C++ library which provides a concise IDL-like interface for binding C++ classes and functions to Python. Leveraging the full power of C++ compile-time introspection and of recently developed metaprogramming techniques, this is achieved entirely in pure C++, without introducing a new syntax. Boost.Python‘s rich set of features and high-level interface make it possible to engineer packages from the ground up as hybrid systems, giving programmers easy and coherent access to both the efficient compile-time polymorphism of C++ and the extremely convenient run-time polymorphism of Python.

Python和C++两种语言在很多方面都是不同的:C++被编译成机器码,Python是解释型。Python的动态类型系统常常被认为是其灵活性的基础,而在C++中,静态类型是其效率的基石。C++具有复杂而困难的编译时元语言,而在Python中,几乎所有事情都发生在运行时。

Python and C++ are in many ways as different as two languages could be: while C++ is usually compiled to machine-code, Python is interpreted. Python‘s dynamic type system is often cited as the foundation of its flexibility, while in C++ static typing is the cornerstone of its efficiency. C++ has an intricate and difficult compile-time meta-language, while in Python, practically everything happens at runtime.

对于许多程序员来说,这些差异意味着Python和C++可以完美地互补。Python程序的性能瓶颈可以在C++中重写为最大速度,强大的C++库的作者选择Python作为中间件语言,以实现其灵活的系统集成能力。此外,表面差异掩盖了一些强烈的相似之处:

Yet for many programmers, these very differences mean that Python and C++ complement one another perfectly. Performance bottlenecks in Python programs can be rewritten in C++ for maximal speed, and authors of powerful C++ libraries choose Python as a middleware language for its flexible system integration capabilities. Furthermore, the surface differences mask some strong similarities:

鉴于Python丰富的“C”互操作性API,原则上应该可以向Python公开C++类型和函数接口,并提供与C++对应接口类似的接口。但是,Python单独提供的用于与C++集成的工具相对较少。与C++和Python相比,“C”只有非常基本的抽象功能,而且完全不支持异常处理。“C”扩展模块编写者需要手工管理Python引用计数,这既烦人又极其容易出错。传统的扩展模块也倾向于包含大量的样板代码重复,这使得它们难以维护,尤其是在包装演进的API时。

Given Python‘s rich ‘C‘ interoperability API, it should in principle be possible to expose C++ type and function interfaces to Python with an analogous interface to their C++ counterparts. However, the facilities provided by Python alone for integration with C++ are relatively meager. Compared to C++ and Python, ‘C‘ has only very rudimentary abstraction facilities, and support for exception-handling is completely missing. ‘C‘ extension module writers are required to manually manage Python reference counts, which is both annoyingly tedious and extremely error-prone. Traditional extension modules also tend to contain a great deal of boilerplate code repetition which makes them difficult to maintain, especially when wrapping an evolving API.

这些限制导致了各种包装系统(wrapping systems)的开发。SWIG可能是用于集成C/C++和Python的最流行的包。最近的一个开发是SIP,它专门为将Python与Qt图形用户界面库连接而设计。SWIG和SIP都引入了自己的专用语言来定制语言间绑定。这有一定的优点,但是必须处理三种不同的语言(Python、C/C++和接口语言)也会带来实际和心理上的困难。CXX包演示了一个有趣的替代方案。它表明Python的“C”API至少有一部分可以通过一个更加用户友好的C++接口来包装和显示。但是,与SWIG和SIP不同,CXX不支持将C++类包装为新的Python类型。

These limitations have lead to the development of a variety of wrapping systems. SWIG is probably the most popular package for the integration of C/C++ and Python. A more recent development is SIP, which was specifically designed for interfacing Python with the Qt graphical user interface library. Both SWIG and SIP introduce their own specialized languages for customizing inter-language bindings. This has certain advantages, but having to deal with three different languages (Python, C/C++ and the interface language) also introduces practical and mental difficulties. The CXX package demonstrates an interesting alternative. It shows that at least some parts of Python‘s ‘C‘ API can be wrapped and presented through a much more user-friendly C++ interface. However, unlike SWIG and SIP, CXX does not include support for wrapping C++ classes as new Python types.

Boost.Python的特性和目标与许多其他系统有很大的重叠。也就是说,Boost.Python试图在不引入单独包装语言的情况下最大限度地提高方便性和灵活性。相反,它为用户提供了一个高级C++接口,用于包装C++类和函数,并通过静态元编程在幕后管理大量的复杂性。Boost.Python也超出了早期系统的范围,它提供:

The features and goals of Boost.Python overlap significantly with many of these other systems. That said, Boost.Python attempts to maximize convenience and flexibility without introducing a separate wrapping language. Instead, it presents the user with a high-level C++ interface for wrapping C++ classes and functions, managing much of the complexity behind-the-scenes with static metaprogramming. Boost.Python also goes beyond the scope of earlier systems by providing:

激发Boost.Python开发的关键是传统扩展模块中的许多样板代码可以使用C++编译时自省来消除。包装C++函数的每个参数都必须使用依赖于参数类型的过程从Python对象中提取。类似地,函数的返回类型决定了如何将返回值从C++转换为Python。当然,参数和返回类型是每个函数类型的一部分,而这正是Boost.Python推导所需的大部分信息的来源。

The key insight that sparked the development of Boost.Python is that much of the boilerplate code in traditional extension modules could be eliminated using C++ compile-time introspection. Each argument of a wrapped C++ function must be extracted from a Python object using a procedure that depends on the argument type. Similarly the function‘s return type determines how the return value will be converted from C++ to Python. Of course argument and return types are part of each function‘s type, and this is exactly the source from which Boost.Python deduces most of the information required.

这种方法导致了用户引导的包装: 在纯C++框架中,尽可能直接从要包装的源代码中提取尽可能多的信息,并且用户显式地提供一些额外的信息。大多数的引导是机械的,很少需要实际的干预。因为接口规范是用与公开代码相同的全功能语言编写的,所以当用户确实需要控制时,她拥有前所未有的能力。

This approach leads to user guided wrapping: as much information is extracted directly from the source code to be wrapped as is possible within the framework of pure C++, and some additional information is supplied explicitly by the user. Mostly the guidance is mechanical and little real intervention is required. Because the interface specification is written in the same full-featured language as the code being exposed, the user has unprecedented power available when she does need to take control.

Boost.Python的主要目标是允许用户仅使用C++编译器向Python公开C++类和函数。总的来说,用户体验应该是直接从Python操作C++对象。

The primary goal of Boost.Python is to allow users to expose C++ classes and functions to Python using nothing more than a C++ compiler. In broad strokes, the user experience should be one of directly manipulating C++ objects from Python.

但是,也不要把所有接口都翻译得太过字面化,这一点也很重要: 每种语言的习惯用法都必须得到尊重。例如,虽然C++和Python都有迭代器的概念,但是它们的表达方式非常不同。Boost.Python必须能够跨越接口的鸿沟。

However, it‘s also important not to translate all interfaces too literally: the idioms of each language must be respected. For example, though C++ and Python both have an iterator concept, they are expressed very differently. Boost.Python has to be able to bridge the interface gap.

必须有可能使Python用户避免因误用C++接口(例如访问已经删除的对象)而导致的崩溃。同样,这个库应该将C++用户与低级Python“C”API隔离开来,用更健壮的替代方案来替代容易出错的“C”接口,比如手工引用计数管理和原始PyObject指针。

It must be possible to insulate Python users from crashes resulting from trivial misuses of C++ interfaces, such as accessing already-deleted objects. By the same token the library should insulate C++ users from low-level Python ‘C‘ API, replacing error-prone ‘C‘ interfaces like manual reference-count management and raw PyObject pointers with more-robust alternatives.

支持基于组件的开发是至关重要的,这样可以将暴露在一个扩展模块中的C++类型传递给暴露在另一个扩展模块中的函数,而不会丢失诸如C++继承关系之类的关键信息。

Support for component-based development is crucial, so that C++ types exposed in one extension module can be passed to functions exposed in another without loss of crucial information like C++ inheritance relationships.

最后,所有包装必须是非侵入的,不需要修改或甚至不需要查看原始C++源代码。现有的C++库必须由只能访问头文件和二进制文件的第三方包装。

Finally, all wrapping must be non-intrusive, without modifying or even seeing the original C++ source code. Existing C++ libraries have to be wrappable by third parties who only have access to header files and binaries.

现在来预览一下Boost.Python,以及它如何改进Python提供的原始工具。下面是一个我们可能想要公开的函数:

And now for a preview of Boost.Python, and how it improves on the raw facilities offered by Python. Here‘s a function we might want to expose:

char const* greet(unsigned x)

{

static char const* const msgs[] = { "hello", "Boost.Python", "world!" };

if (x > 2)

throw std::range_error("greet: index out of range");

return msgs[x];

}要使用Python ‘C‘ API将这个函数封装在标准C++中,我们需要这样的东西:

To wrap this function in standard C++ using the Python ‘C‘ API, we‘d need something like this:

extern "C" // all Python interactions use 'C' linkage and calling convention

{

// Wrapper to handle argument/result conversion and checking

PyObject* greet_wrap(PyObject* args, PyObject * keywords)

{

int x;

if (PyArg_ParseTuple(args, "i", &x)) // extract/check arguments

{

char const* result = greet(x); // invoke wrapped function

return PyString_FromString(result); // convert result to Python

}

return 0; // error occurred

}

// Table of wrapped functions to be exposed by the module

static PyMethodDef methods[] = {

{ "greet", greet_wrap, METH_VARARGS, "return one of 3 parts of a greeting" }

, { NULL, NULL, 0, NULL } // sentinel

};

// module initialization function

DL_EXPORT init_hello()

{

(void) Py_InitModule("hello", methods); // add the methods to the module

}

}下面是我们用Boost.Python来公开它的包装代码:

Now here‘s the wrapping code we‘d use to expose it with Boost.Python:

#include <boost/python.hpp>

using namespace boost::python;

BOOST_PYTHON_MODULE(hello)

{

def("greet", greet, "return one of 3 parts of a greeting");

}下面是使用情况:

and here it is in action:

>>> import hello

>>> for x in range(3):

... print hello.greet(x)

...

hello

Boost.Python

world!除了“C”API版本更加冗长这一事实之外,值得注意的是它没有正确处理的一些事情:

hello.greet, Boost.Python版本将会引发一个Python异常; 但是另一个(‘C‘API版)将继续执行C++实现, 并将负整数转换为无符号整数(通常包装为某个非常大的数字),并将错误的转换传递给包装的函数。greet()函数使用大于2的参数, 它将抛出一个异常。通常, 如果一个C++异常在一个‘C‘编译器生成的代码之间传播, 它将导致崩溃. 正如您在第一个版本中看到的, 在这里没有C++脚手架来防止这种情况发生。通过Boost.Python包装的函数自动包含一个异常处理层, 它通过将未处理的C++异常转换为相应的Python异常来保护Python用户。x。PyArg_ParseTuple不能转换Python的long(任意精度的整数),这些对象恰好适合unsigned int,但不适合signed long,它也不能处理包装的C++类和用户定义的隐式operator unsigned int()转换. Boost.Python的动态类型转换注册表允许用户添加任意转换方法。Aside from the fact that the ‘C‘ API version is much more verbose, it‘s worth noting a few things that it doesn‘t handle correctly:

本节概述了该库的一些主要特性。除了有必要避免混淆之外,我们省略了库实现的细节。

This section outlines some of the library‘s major features. Except as neccessary to avoid confusion, details of library implementation are omitted.

C++类和结构是用类似的简洁接口公开的。给定:

C++ classes and structs are exposed with a similarly-terse interface. Given:

struct World

{

void set(std::string msg) { this->msg = msg; }

std::string greet() { return msg; }

std::string msg;

};下面的代码将在我们的扩展模块中公开它:

The following code will expose it in our extension module:

#include <boost/python.hpp>

BOOST_PYTHON_MODULE(hello)

{

class_<World>("World")

.def("greet", &World::greet)

.def("set", &World::set)

;

}虽然这个代码有某种python的熟悉性,但人们有时会发现语法有点混乱,因为它看起来不像它们所习惯的大多数C++代码。尽管如此, 这只是标准C++。由于灵活的语法和操作符重载, C++和Python对于定义特定于领域的(子)语言(DSLs)非常重要,这就是我们在Boost.Python中所做的。分解一下:

Although this code has a certain pythonic familiarity, people sometimes find the syntax bit confusing because it doesn‘t look like most of the C++ code they‘re used to. All the same, this is just standard C++. Because of their flexible syntax and operator overloading, C++ and Python are great for defining domain-specific (sub)languages (DSLs), and that‘s what we‘ve done in Boost.Python. To break it down:

class_<World>("World")构造一个class_<World>类型的未命名对象,并将“World”传递给它的构造函数。这将在扩展模块中创建一个名为World的新型Python类,并将其与Boost.Python类型转换注册表中的C++类型World关联起来。我们也可以这样写:

constructs an unnamed object of type class_

class_<World> w("World");但是那样会更冗长,因为我们必须再次命名w来调用它的def()成员函数:

but that would‘ve been more verbose, since we‘d have to name w again to invoke its def() member function:

w.def("greet", &World::greet)链式操作*, 在最初的示例中,用于成员访问的点的位置没有什么特殊之处: C++允许符号两侧有任何数量的空格, 并把点放在每行的开头可以让我们用统一的语法连接任意多的对成员函数的连续调用。允许链接的另一个关键事实是class_<>成员函数都返回对*this的引用。

There‘s nothing special about the location of the dot for member access in the original example: C++ allows any amount of whitespace on either side of a token, and placing the dot at the beginning of each line allows us to chain as many successive calls to member functions as we like with a uniform syntax. The other key fact that allows chaining is that class_<> member functions all return a reference to *this.

所以这个例子等价于:

So the example is equivalent to:

class_<World> w("World");

w.def("greet", &World::greet);

w.def("set", &World::set);以这种方式分解Boost.Python类包装器的组件有时是有用的,但是本文的其余部分将坚持简洁的语法。

It‘s occasionally useful to be able to break down the components of a Boost.Python class wrapper in this way, but the rest of this article will stick to the terse syntax.

为了完整起见,下面是包装类的使用:

For completeness, here‘s the wrapped class in use:

>>> import hello

>>> planet = hello.World()

>>> planet.set('howdy')

>>> planet.greet()

'howdy'由于我们的World类只是一个普通的struct,它有一个隐式无参数(null)构造函数。Boost.Python默认情况下公开null构造函数,这就是为什么我们能够编写:

Since our World class is just a plain struct, it has an implicit no-argument (nullary) constructor. Boost.Python exposes the nullary constructor by default, which is why we were able to write:

>>> planet = hello.World()然而,任何语言中设计良好的类都可能需要构造函数参数来建立它们的不变量。与Python不同,在Python中__init__只是一个特殊命名的方法,在C++中构造函数不能像普通成员函数那样处理。特别是我们不能访问他们的地址: &World::World是一个错误。该库为指定构造函数提供了不同的接口. 给定:

However, well-designed classes in any language may require constructor arguments in order to establish their invariants. Unlike Python, where init is just a specially-named method, In C++ constructors cannot be handled like ordinary member functions. In particular, we can‘t take their address: &World::World is an error. The library provides a different interface for specifying constructors. Given:

struct World

{

World(std::string msg); // added constructor

...我们可以修改我们的包装代码如下:

we can modify our wrapping code as follows:

class_<World>("World", init<std::string>())

...当然,C++类可能有额外的构造函数,我们也可以通过传递更多的init<…>实例给def()来公开它们:

of course, a C++ class may have additional constructors, and we can expose those as well by passing more instances of init<...> to def():

class_<World>("World", init<std::string>())

.def(init<double, double>())

...Boost.Python允许重载包装的函数、成员函数和构造函数,以镜像C++重载。

Boost.Python allows wrapped functions, member functions, and constructors to be overloaded to mirror C++ overloading.

C++类中任何可公开访问的数据成员都可以很容易地公开为只读或读写属性:

Any publicly-accessible data members in a C++ class can be easily exposed as either readonly or readwrite attributes:

class_<World>("World", init<std::string>())

.def_readonly("msg", &World::msg)

...并且可以直接在Python中使用:

and can be used directly in Python:

>>> planet = hello.World('howdy')

>>> planet.msg

'howdy'这不会导致向World实例__dict__添加属性,这会在包装大型数据结构时节省大量内存。事实上,除非从Python中显式地添加属性,否则根本不会创建实例__dict__。Boost.Python将这种功能归功于新的Python 2.2类型系统,特别是描述符接口和property类型。

This does not result in adding attributes to the World instance __dict__, which can result in substantial memory savings when wrapping large data structures. In fact, no instance __dict__ will be created at all unless attributes are explicitly added from Python. Boost.Python owes this capability to the new Python 2.2 type system, in particular the descriptor interface and property type.

在C++中,可公开访问的数据成员被认为是糟糕设计的标志,因为它们破坏了封装,而样式指南通常规定使用“getter”和“setter”函数。但是,在Python中,__getattr__、__setattr__和从2.2起,property意味着属性访问只是程序员可以使用的一种封装得更好的语法工具。Boost.Python通过让用户可以直接创建Python属性,弥补了这个习惯用法上的差距。如果msg是私有的,我们仍然可以将它作为属性在Python中公开,如下所示:

In C++, publicly-accessible data members are considered a sign of poor design because they break encapsulation, and style guides usually dictate the use of "getter" and "setter" functions instead. In Python, however, __getattr__,__setattr__, and since 2.2, property mean that attribute access is just one more well-encapsulated syntactic tool at the programmer‘s disposal. Boost.Python bridges this idiomatic gap by making Python property creation directly available to users. If msg were private, we could still expose it as attribute in Python as follows:

class_<World>("World", init<std::string>())

.add_property("msg", &World::greet, &World::set)

...上面的例子反映了Python 2.2+中属性的常见用法:

The example above mirrors the familiar usage of properties in Python 2.2+:

class World(object):

__init__(self, msg):

self.__msg = msg

def greet(self):

return self.__msg

def set(self, msg):

self.__msg = msg

msg = property(greet, set)为用户定义的类型编写算术运算符的能力是这两种语言成功进行数值计算的一个主要因素,而像NumPy这样的包的成功证明了在扩展模块中公开运算符的能力。Boost.Python为包装操作符重载提供了一种简洁的机制。下面的例子显示了Boost rational number库包装器的一个片段:

The ability to write arithmetic operators for user-defined types has been a major factor in the success of both languages for numerical computation, and the success of packages like NumPy attests to the power of exposing operators in extension modules. Boost.Python provides a concise mechanism for wrapping operator overloads. The example below shows a fragment from a wrapper for the Boost rational number library:

class_<rational<int> >("rational_int")

.def(init<int, int>()) // constructor, e.g. rational_int(3,4)

.def("numerator", &rational<int>::numerator)

.def("denominator", &rational<int>::denominator)

.def(-self) // __neg__ (unary minus)

.def(self + self) // __add__ (homogeneous)

.def(self * self) // __mul__

.def(self + int()) // __add__ (heterogenous)

.def(int() + self) // __radd__

...魔术是使用“表达式模板”的简化应用程序来实现的[VELD1995],该技术最初是为优化高性能矩阵代数表达式而开发的。其本质是,操作符不是立即执行计算,而是重载来构造表示计算的类型。在矩阵代数中,当可以考虑整个表达式的结构时,通常可以进行戏剧性的优化,而不是“贪婪地”计算每个操作。Boost.Python使用相同的技术基于涉及self的表达式构建适当的Python方法对象。

The magic is performed using a simplified application of "expression templates" [VELD1995], a technique originally developed for optimization of high-performance matrix algebra expressions. The essence is that instead of performing the computation immediately, operators are overloaded to construct a type representing the computation. In matrix algebra, dramatic optimizations are often available when the structure of an entire expression can be taken into account, rather than evaluating each operation "greedily". Boost.Python uses the same technique to build an appropriate Python method object based on expressions involving self.

C++继承关系在Boost.Python可以通过添加一个可选的bases<…>参数到class_<…>模板参数列表, 如下:

C++ inheritance relationships can be represented to Boost.Python by adding an optional bases<...> argument to the class_<...> template parameter list as follows:

class_<Derived, bases<Base1,Base2> >("Derived")

...这有两个影响:

class_<……>创建时,会在Boost.Python中类型对象注册表中查找与Base1和Base2对应的Python类型对象,并用作新的PythonDerived类型对象的基类,因此,为Python Base1和Base2类型公开的方法将自动成为Derived类型的成员。因为注册表是全局的,所以即使Derived类所在的模块与它任意一个基类公开在不同的模块中,也可以正确地工作。Derived到它的基类的C++转换被添加到Boost.Python注册表中。因此,期望(指针或引用)基类型对象的封装C++方法可以通过封装Derived的实例调用。类T的包装成员函数被视为具有第一个参数隐式参数T&,因此,为了允许为派生对象调用基类方法,这些转换是必要的。This has two effects:

当然,可以从包装好的C++类派生新的Python类。因为Boost.Python使用了新型的类系统,它与Python内置类型的工作方式非常相似。这里,有一个重要的细节不同:内置类型通常在__new__函数中建立它们的不变量,因此派生类在调用其方法之前不需要在基类上调用__init__:

Of course it‘s possible to derive new Python classes from wrapped C++ class instances. Because Boost.Python uses the new-style class system, that works very much as for the Python built-in types. There is one significant detail in which it differs: the built-in types generally establish their invariants in their new function, so that derived classes do not need to call init on the base class before invoking its methods :

>>> class L(list):

... def __init__(self):

... pass

...

>>> L().reverse()

>>>由于C++对象构造是一步操作,在__init__函数中,在参数可用之前,不能构造C++实例数据:

Because C++ object construction is a one-step operation, C++ instance data cannot be constructed until the arguments are available, in the init function:

>>> class D(SomeBoostPythonClass):

... def __init__(self):

... pass

...

>>> D().some_boost_python_method()

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in ?

TypeError: bad argument type for built-in operation这种情况发生是因为Boost.Python在D实例中无法找到SomeBoostPythonClass实例数据; D在基类上的__init__函数的隐式构造。它可以通过删除D的__init__函数或调用SomeBoostPythonClass.__init__(…)显式来纠正它。

This happened because Boost.Python couldn‘t find instance data of type SomeBoostPythonClass within the D instance; D‘s init function masked construction of the base class. It could be corrected by either removing D‘s init function or having it call SomeBoostPythonClass.__init__(...) explicitly.

从扩展类派生Python类不是很有趣,除非它们可以从C++中以多形态使用。换句话说,当通过C++的基类指针/引用调用时,Python方法实现看起来应该覆盖C++虚函数的实现。由于改变虚函数行为的唯一方法是在派生类中重写它,因此用户必须构建一个特殊的派生类来分派多态类的虚函数:

Deriving new types in Python from extension classes is not very interesting unless they can be used polymorphically from C++. In other words, Python method implementations should appear to override the implementation of C++ virtual functions when called through base class pointers/references from C++. Since the only way to alter the behavior of a virtual function is to override it in a derived class, the user must build a special derived class to dispatch a polymorphic class‘ virtual functions:

//

// interface to wrap:

//

class Base

{

public:

virtual int f(std::string x) { return 42; }

virtual ~Base();

};

int calls_f(Base const& b, std::string x) { return b.f(x); }

//

// Wrapping Code

//

// Dispatcher class

struct BaseWrap : Base

{

// Store a pointer to the Python object

BaseWrap(PyObject* self_) : self(self_) {}

PyObject* self;

// Default implementation, for when f is not overridden

int f_default(std::string x) { return this->Base::f(x); }

// Dispatch implementation

int f(std::string x) { return call_method<int>(self, "f", x); }

};

...

def("calls_f", calls_f);

class_<Base, BaseWrap>("Base")

.def("f", &Base::f, &BaseWrap::f_default)

;Now here‘s some Python code which demonstrates:

>>> class Derived(Base):

... def f(self, s):

... return len(s)

...

>>> calls_f(Base(), 'foo')

42

>>> calls_f(Derived(), 'forty-two')

9关于dispatcher类需要注意的事项:

call_method调用,它使用与C++函数包装相同的全局类型转换注册表,将参数从C++转换为Python,并将返回类型从Python转换为C++。PyObject*参数进行复制call_methodf_default成员函数;在BaseWrap类型的对象上不能调用Base::f,因为它覆盖了f。Things to notice about the dispatcher class:

诚然,这个公式重复起来很乏味,尤其是在有许多多态类的项目上。它的必要性反映了C++编译时自省功能的一些局限性:无法枚举类的成员并找出哪些是虚函数。至少有一个非常有前途的项目已经开始编写前端,它可以从C++标头自动生成这些分派器(和其他包装代码)。

Admittedly, this formula is tedious to repeat, especially on a project with many polymorphic classes. That it is neccessary reflects some limitations in C++‘s compile-time introspection capabilities: there‘s no way to enumerate the members of a class and find out which are virtual functions. At least one very promising project has been started to write a front-end which can generate these dispatchers (and other wrapping code) automatically from C++ headers.

Pyste is being developed by Bruno da Silva de Oliveira. It builds on GCC_XML, which generates an XML version of GCC‘s internal program representation. Since GCC is a highly-conformant C++ compiler, this ensures correct handling of the most-sophisticated template code and full access to the underlying type system. In keeping with the Boost.Python philosophy, a Pyste interface description is neither intrusive on the code being wrapped, nor expressed in some unfamiliar language: instead it is a 100% pure Python script. If Pyste is successful it will mark a move away from wrapping everything directly in C++ for many of our users. It will also allow us the choice to shift some of the metaprogram code from C++ to Python. We expect that soon, not only our users but the Boost.Python developers themselves will be "thinking hybrid" about their own code.

序列化是将内存中的对象转换为可以存储在磁盘上或通过网络连接发送的数据的过程。序列化的对象(通常是纯字符串)可以检索并转换回原始对象。一个好的序列化系统将自动转换整个对象层次结构。Python的标准pickle模块就是这样一个系统。它利用该语言强大的运行时自省功能来序列化实际任意用户定义的对象。通过一些简单和无干扰的规定,这个强大的机制可以扩展到也适用于包装的C++对象。下面是一个例子:

Serialization is the process of converting objects in memory to a form that can be stored on disk or sent over a network connection. The serialized object (most often a plain string) can be retrieved and converted back to the original object. A good serialization system will automatically convert entire object hierarchies. Python‘s standard pickle module is just such a system. It leverages the language‘s strong runtime introspection facilities for serializing practically arbitrary user-defined objects. With a few simple and unintrusive provisions this powerful machinery can be extended to also work for wrapped C++ objects. Here is an example:

#include <string>

struct World

{

World(std::string a_msg) : msg(a_msg) {}

std::string greet() const { return msg; }

std::string msg;

};

#include <boost/python.hpp>

using namespace boost::python;

struct World_picklers : pickle_suite

{

static tuple

getinitargs(World const& w) { return make_tuple(w.greet()); }

};

BOOST_PYTHON_MODULE(hello)

{

class_<World>("World", init<std::string>())

.def("greet", &World::greet)

.def_pickle(World_picklers())

;

}现在让我们创建一个World对象,并把它保存在磁盘上:

Now let‘s create a World object and put it to rest on disk:

>>> import hello

>>> import pickle

>>> a_world = hello.World("howdy")

>>> pickle.dump(a_world, open("my_world", "w"))在可能不同的计算机上使用可能不同的脚本,使用可能不同的操作系统:???

In a potentially different script on a potentially different computer with a potentially different operating system:

>>> import pickle

>>> resurrected_world = pickle.load(open("my_world", "r"))

>>> resurrected_world.greet()

'howdy'当然,cPickle模块也可以用于更快的处理。

Of course the cPickle module can also be used for faster processing.

Boost.Python的pickle_suite完全支持标准Python文档中定义的pickle协议。就像Python中的__getinitargs__函数一样,pickle_suite的getinitargs()负责创建将用于重构pickle对象的参数元组。Python pickle协议的其他元素__getstate__和__setstate__可以通过C++ getstate和setstate函数选择性地提供。C++的静态类型系统允许库在编译时确保不使用无意义的函数组合(例如getstate没有setstate)。

Boost.Python‘s pickle_suite fully supports the pickle protocol defined in the standard Python documentation. Like a getinitargs function in Python, the pickle_suite‘s getinitargs() is responsible for creating the argument tuple that will be use to reconstruct the pickled object. The other elements of the Python pickling protocol, getstate and setstate can be optionally provided via C++ getstate and setstate functions. C++‘s static type system allows the library to ensure at compile-time that nonsensical combinations of functions (e.g. getstate without setstate) are not used.

要实现更复杂的C++对象的序列化,需要做的工作比上面示例中显示的要多一些。幸运的是,对象接口(请参阅下一节)极大地帮助保持代码的可管理性。

Enabling serialization of more complex C++ objects requires a little more work than is shown in the example above. Fortunately the object interface (see next section) greatly helps in keeping the code manageable.

有经验的“C”语言扩展模块作者将熟悉无处不在的PyObject*、手动引用计数,以及需要记住哪个API调用返回“新的”(拥有的)引用或“借来的”(原始的)引用。这些约束不仅麻烦,而且是错误的主要来源,特别是在出现异常的情况下。

Experienced ‘C‘ language extension module authors will be familiar with the ubiquitous PyObject*, manual reference-counting, and the need to remember which API calls return "new" (owned) references or "borrowed" (raw) references. These constraints are not just cumbersome but also a major source of errors, especially in the presence of exceptions.

Boost.Python提供了一个object对象,它自动化引用计数,并提供从任意类型的C++对象到Python的转换。这大大减少了预期的扩展模块编写人员的学习工作量。

Boost.Python provides a class object which automates reference counting and provides conversion to Python from C++ objects of arbitrary type. This significantly reduces the learning effort for prospective extension module writers.

从任何其他类型创建对象是非常简单的:

Creating an object from any other type is extremely simple:

object s("hello, world"); // s manages a Python stringobject具有与所有其他类型的模板化交互,并具有自动到python的转换。它发生得如此自然以至于很容易被忽略:

object has templated interactions with all other types, with automatic to-python conversions. It happens so naturally that it‘s easily overlooked:

object ten_Os = 10 * s[4]; // -> "oooooooooo"在上面的示例中,在调用索引和乘法操作之前,4和10被转换为Python对象。

In the example above, 4 and 10 are converted to Python objects before the indexing and multiplication operations are invoked.

extract<T>类模板可以用来将Python对象转换为C++类型:

The extract

double x = extract<double>(o);如果无法执行任何方向的转换,将在运行时引发适当的异常。

If a conversion in either direction cannot be performed, an appropriate exception is thrown at runtime.

object类型附带一组派生类型,尽可能多地反映Python内置类型,如list、dict、tuple等。这使得从C++方便地操作这些高级类型:

The object type is accompanied by a set of derived types that mirror the Python built-in types such as list, dict, tuple, etc. as much as possible. This enables convenient manipulation of these high-level types from C++:

dict d;

d["some"] = "thing";

d["lucky_number"] = 13;

list l = d.keys();这看起来和工作起来都很像普通的Python代码,但是它是纯C++的。当然,我们可以封装接受或返回对象实例的C++函数。

This almost looks and works like regular Python code, but it is pure C++. Of course we can wrap C++ functions which accept or return object instances.

由于混合编程语言在实践和心理上的困难,在任何开发工作一开始就使用一种语言是很常见的。对于许多应用程序,性能考虑要求为核心算法使用编译语言。不幸的是,由于静态类型系统的复杂性,我们为运行时性能所付出的代价通常是开发时间的显著增加。经验表明,编写可维护的C++代码通常比开发类似的Python代码需要更长的时间和更多的辛苦工作经验。即使开发人员可以完全使用编译语言,他们通常也会为了用户的利益,通过某种特殊的脚本层来增强系统,而不会利用相同的优势。

Because of the practical and mental difficulties of combining programming languages, it is common to settle a single language at the outset of any development effort. For many applications, performance considerations dictate the use of a compiled language for the core algorithms. Unfortunately, due to the complexity of the static type system, the price we pay for runtime performance is often a significant increase in development time. Experience shows that writing maintainable C++ code usually takes longer and requires far more hard-earned working experience than developing comparable Python code. Even when developers are comfortable working exclusively in compiled languages, they often augment their systems by some type of ad hoc scripting layer for the benefit of their users without ever availing themselves of the same advantages.

Boost.Python使我们能够混合思考。Python可以用于快速原型化一个新的应用程序;它的易用性和大量的标准库使我们在通往工作系统的道路上领先一步。如果需要,可以使用工作代码来发现限速热点。为了最大限度地提高性能,这些可以在C++中重新实现,并使用Boost.Python绑定将它们带回现有的高级过程。

Boost.Python enables us to think hybrid. Python can be used for rapidly prototyping a new application; its ease of use and the large pool of standard libraries give us a head start on the way to a working system. If necessary, the working code can be used to discover rate-limiting hotspots. To maximize performance these can be reimplemented in C++, together with the Boost.Python bindings needed to tie them back into the existing higher-level procedure.

当然,如果从一开始就很清楚许多算法最终将不得不在C++中实现,那么这种自顶向下的方法就不那么有吸引力了。幸运的是Boost.Python还允许我们采用自底向上的方法。我们在科学应用工具箱的开发中非常成功地使用了这种方法。工具箱最初主要是一个带有Boost.Python绑定的C++类库,并且在一段时间内增长主要集中在C++部分。然而,随着工具箱变得越来越完整,越来越多新添加的功能可以在Python中实现.

Of course, this top-down approach is less attractive if it is clear from the start that many algorithms will eventually have to be implemented in C++. Fortunately Boost.Python also enables us to pursue a bottom-up approach. We have used this approach very successfully in the development of a toolbox for scientific applications. The toolbox started out mainly as a library of C++ classes with Boost.Python bindings, and for a while the growth was mainly concentrated on the C++ parts. However, as the toolbox is becoming more complete, more and more newly added functionality can be implemented in Python.

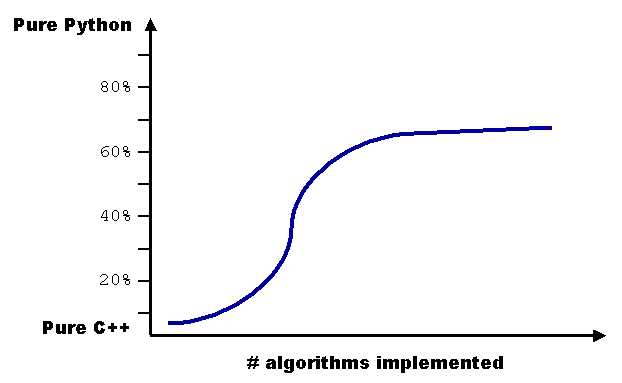

这个数字显示了随着新算法的实现,新添加的C++和Python代码的估计比例。我们期望这个比率能达到70%的Python。能够在Python中解决新问题,而不是更困难的静态类型语言,这是我们在boost.Python中投资的回报。从Python获取所有代码的能力允许更广泛的开发人员开发新的应用程序。

This figure shows the estimated ratio of newly added C++ and Python code over time as new algorithms are implemented. We expect this ratio to level out near 70% Python. Being able to solve new problems mostly in Python rather than a more difficult statically typed language is the return on our investment in Boost.Python. The ability to access all of our code from Python allows a broader group of developers to use it in the rapid development of new applications.

第一个版本的Boost.Python是在2000年由Dave Abrahams在龙系统开发,在那里他很有机会让蒂姆·彼得斯(Tim Peters)成为“Python的禅宗”的指南。戴夫的一个工作就是开发一个基于python的自然语言处理系统。由于它最终将锁定嵌入式硬件,所以通常假设计算-密集型核心将是C++以优化速度和内存占用。该项目还希望通过Python测试scripts测试所有的C++代码。我们已知的绑定C++和Python的唯一工具是SWIG,在它处理C++时,它很弱。在这一点上,声称对Boost.Python方法的可能优点有深入的了解是错误的。Dave对花式C++模板技巧的兴趣和专业知识刚刚达到可以对其进行一些真正破坏的程度,Boost.Python就这样出现了,因为它满足了需求,而且它看起来是一种很酷的尝试。

The first version of Boost.Python was developed in 2000 by Dave Abrahams at Dragon Systems, where he was privileged to have Tim Peters as a guide to "The Zen of Python". One of Dave‘s jobs was to develop a Python-based natural language processing system. Since it was eventually going to be targeting embedded hardware, it was always assumed that the compute-intensive core would be rewritten in C++ to optimize speed and memory footprint1. The project also wanted to test all of its C++ code using Python test scripts2. The only tool we knew of for binding C++ and Python was SWIG, and at the time its handling of C++ was weak. It would be false to claim any deep insight into the possible advantages of Boost.Python‘s approach at this point. Dave‘s interest and expertise in fancy C++ template tricks had just reached the point where he could do some real damage, and Boost.Python emerged as it did because it filled a need and because it seemed like a cool thing to try.

这个早期版本的目标是我们在本文中描述的许多相同的基本目标, 最明显的不同在于语法稍微有些笨拙,缺乏对操作符重载、pickling和基于组件开发的特殊支持。最后三个功能由Ullrich Koethe和Ralf Grosse-Kunstleve快速添加,其他热情的贡献者为嵌套模块和静态成员功能提供支持。

This early version was aimed at many of the same basic goals we‘ve described in this paper, differing most-noticeably by having a slightly more cumbersome syntax and by lack of special support for operator overloading, pickling, and component-based development. These last three features were quickly added by Ullrich Koethe and Ralf Grosse-Kunstleve3, and other enthusiastic contributors arrived on the scene to contribute enhancements like support for nested modules and static member functions.

到2001年早期,发展已经稳定,但还没有增加一些新功能,然而,一个令人不安的新事实出现了:Ralf已经开始测试Boost.Python使用EDG前端的编译器的预发布版本, 而Boost.Python的核心机制,负责处理Python和C++类型之间的转换,却无法编译。事实证明,我们在所有经过测试的C++编译器的实现中都利用了一个非常常见的bug. 我们知道,随着C++编译器迅速变得更加符合标准,库将开始在更多平台上失败。不幸的是,由于该机制对库的功能至关重要,解决这个问题看起来非常困难。

By early 2001 development had stabilized and few new features were being added, however a disturbing new fact came to light: Ralf had begun testing Boost.Python on pre-release versions of a compiler using the EDG front-end, and the mechanism at the core of Boost.Python responsible for handling conversions between Python and C++ types was failing to compile. As it turned out, we had been exploiting a very common bug in the implementation of all the C++ compilers we had tested. We knew that as C++ compilers rapidly became more standards-compliant, the library would begin failing on more platforms. Unfortunately, because the mechanism was so central to the functioning of the library, fixing the problem looked very difficult.

幸运的是,那年晚些时候,劳伦斯·伯克利(Lawrence Berkeley)和后来的劳伦斯·利弗莫尔(Lawrence Livermore)的国家实验室与Boost咨询公司签订支持和开发Boost.Python的合同,这是一个解决基本问题和确保库未来的新机会。重新设计的工作开始于低级别的转换架构,按照标准构建并支持基于组件的开发(???与版本1相反,转换必须跨模块边界显式地导入和导出???)。对Python和C++对象之间的关系进行了新的分析,从而更直观地处理了C++的lvalues和rvalues。

Fortunately, later that year Lawrence Berkeley and later Lawrence Livermore National labs contracted with Boost Consulting for support and development of Boost.Python, and there was a new opportunity to address fundamental issues and ensure a future for the library. A redesign effort began with the low level type conversion architecture, building in standards-compliance and support for component-based development (in contrast to version 1 where conversions had to be explicitly imported and exported across module boundaries). A new analysis of the relationship between the Python and C++ objects was done, resulting in more intuitive handling for C++ lvalues and rvalues.

Python 2.2中出现了一个功能强大的新类型系统,这使得是否要保持与Python 1.5.2的兼容性变得很容易:仅仅为了模拟经典Python类而丢弃大量复杂代码的机会实在是太好了,不能错过。此外,Python迭代器和描述符为表示类似的C++结构提供了关键而优雅的工具。通用object接口的开发使我们能够进一步保护C++程序员免受Python“C”API的危险和语法负担。在此期间还添加了许多其他特性,包括C++异常转换、对重载函数的改进支持,以及最重要的处理指针和引用的调用策略。

The emergence of a powerful new type system in Python 2.2 made the choice of whether to maintain compatibility with Python 1.5.2 easy: the opportunity to throw away a great deal of elaborate code for emulating classic Python classes alone was too good to pass up. In addition, Python iterators and descriptors provided crucial and elegant tools for representing similar C++ constructs. The development of the generalized object interface allowed us to further shield C++ programmers from the dangers and syntactic burdens of the Python ‘C‘ API. A great number of other features including C++ exception translation, improved support for overloaded functions, and most significantly, CallPolicies for handling pointers and references, were added during this period.

2002年10月,Boost.Python发布了版本2。从那时起,开发工作就集中在改进对C++运行时多态性和智能指针的支持上。Peter Dimov巧妙的boost::shared_ptr设计使我们能够为混合开发人员提供一个一致的界面,以便在不丢失信息的情况下跨语言障碍来回移动对象。起初,我们担心Boost.Python v2实现的复杂性和复杂性可能会阻碍贡献者,但是Pyste和其他几个重要特性的出现消除了这些担忧。关于Python C++ -sig的日常问题和所需改进的积压说明这个库正在被使用。对我们来说,未来是光明的。

In October 2002, version 2 of Boost.Python was released. Development since then has concentrated on improved support for C++ runtime polymorphism and smart pointers. Peter Dimov‘s ingenious boost::shared_ptr design in particular has allowed us to give the hybrid developer a consistent interface for moving objects back and forth across the language barrier without loss of information. At first, we were concerned that the sophistication and complexity of the Boost.Python v2 implementation might discourage contributors, but the emergence of Pyste and several other significant feature contributions have laid those fears to rest. Daily questions on the Python C++-sig and a backlog of desired improvements show that the library is getting used. To us, the future looks bright.

Boost.Python实现了两个丰富且互补的语言环境之间的无缝互操作性。因为它利用模板元编程来反省类型和函数,所以用户永远不需要学习第三种语法:接口定义是用简洁且可维护的C++编写的。而且,包装系统不需要解析C++标头或表示类型系统:编译器为我们做这些工作。

Boost.Python achieves seamless interoperability between two rich and complimentary language environments. Because it leverages template metaprogramming to introspect about types and functions, the user never has to learn a third syntax: the interface definitions are written in concise and maintainable C++. Also, the wrapping system doesn‘t have to parse C++ headers or represent the type system: the compiler does that work for us.

计算密集型任务发挥C++的优势,通常不可能在纯Python中高效地实现,而在Python中像微不足道的序列化之类的作业在纯C++中是非常困难的。考虑到从头开始构建混合软件系统的奢侈性,我们可以以新的信心和能力来处理设计。

Computationally intensive tasks play to the strengths of C++ and are often impossible to implement efficiently in pure Python, while jobs like serialization that are trivial in Python can be very difficult in pure C++. Given the luxury of building a hybrid software system from the ground up, we can approach design with new confidence and power.

[VELD1995] T. Veldhuizen, "Expression Templates," C++ Report, Vol. 7 No. 5 June 1995, pp. 26-31. http://osl.iu.edu/~tveldhui/papers/Expression-Templates/exprtmpl.html

[1] In retrospect, it seems that "thinking hybrid" from the ground up might have been better for the NLP system: the natural component boundaries defined by the pure python prototype turned out to be inappropriate for getting the desired performance and memory footprint out of the C++ core, which eventually caused some redesign overhead on the Python side when the core was moved to C++.

[2] We also have some reservations about driving all C++ testing through a Python interface, unless that‘s the only way it will be ultimately used. Any transition across language boundaries with such different object models can inevitably mask bugs.

[3] These features were expressed very differently in v1 of Boost.Python

标签:initial error doc 情况下 elements nis tst 不可 rac

原文地址:https://www.cnblogs.com/yaoyu126/p/10116251.html