This article explores Python modules and Python packages, two mechanisms that facilitate modular programming.

Modular programming refers to the process of breaking a large, unwieldy programming task into separate, smaller, more manageable subtasks or modules. Individual modules can then be cobbled together like building blocks to create a larger application.

There are several advantages to modularizing code in a large application:

-

Simplicity: Rather than focusing on the entire problem at hand, a module typically focuses on one relatively small portion of the problem. If you’re working on a single module, you’ll have a smaller problem domain to wrap your head around. This makes development easier and less error-prone.

-

Maintainability: Modules are typically designed so that they enforce logical boundaries between different problem domains. If modules are written in a way that minimizes interdependency, there is decreased likelihood that modifications to a single module will have an impact on other parts of the program. (You may even be able to make changes to a module without having any knowledge of the application outside that module.) This makes it more viable for a team of many programmers to work collaboratively on a large application.

-

Reusability: Functionality defined in a single module can be easily reused (through an appropriately defined interface) by other parts of the application. This eliminates the need to recreate duplicate code.

-

Scoping: Modules typically define a separate namespace, which helps avoid collisions between identifiers in different areas of a program. (One of the tenets in the Zen of Python is Namespaces are one honking great idea—let’s do more of those!)

Functions, modules and packages are all constructs in Python that promote code modularization.

Python Modules: Overview

There are actually three different ways to define a module in Python:

- A module can be written in Python itself.

- A module can be written in C and loaded dynamically at run-time, like the

re(regular expression) module. - A built-in module is intrinsically contained in the interpreter, like the

itertoolsmodule.

A module’s contents are accessed the same way in all three cases: with the importstatement.

Here, the focus will mostly be on modules that are written in Python. The cool thing about modules written in Python is that they are exceedingly straightforward to build. All you need to do is create a file that contains legitimate Python code and then give the file a name with a .py extension. That’s it! No special syntax or voodoo is necessary.

For example, suppose you have created a file called mod.py containing the following:

mod.py

s = "If Comrade Napoleon says it, it must be right."

a = [100, 200, 300]

def foo(arg):

print(f‘arg = {arg}‘)

class Foo:

pass

Several objects are defined in mod.py:

s(a string)a(a list)foo()(a function)Foo(a class)

Assuming mod.py is in an appropriate location, which you will learn more about shortly, these objects can be accessed by importing the module as follows:

>>> import mod

>>> print(mod.s)

If Comrade Napoleon says it, it must be right.

>>> mod.a

[100, 200, 300]

>>> mod.foo([‘quux‘, ‘corge‘, ‘grault‘])

arg = [‘quux‘, ‘corge‘, ‘grault‘]

>>> x = mod.Foo()

>>> x

<mod.Foo object at 0x03C181F0>

The Module Search Path

Continuing with the above example, let’s take a look at what happens when Python executes the statement:

import mod

When the interpreter executes the above import statement, it searches for mod.py in a list of directories assembled from the following sources:

- The directory from which the input script was run or the current directory if the interpreter is being run interactively

- The list of directories contained in the

PYTHONPATHenvironment variable, if it is set. (The format forPYTHONPATHis OS-dependent but should mimic thePATHenvironment variable.) - An installation-dependent list of directories configured at the time Python is installed

The resulting search path is accessible in the Python variable sys.path, which is obtained from a module named sys:

>>> import sys

>>> sys.path

[‘‘, ‘C:\\Users\\john\\Documents\\Python\\doc‘, ‘C:\\Python36\\Lib\\idlelib‘,

‘C:\\Python36\\python36.zip‘, ‘C:\\Python36\\DLLs‘, ‘C:\\Python36\\lib‘,

‘C:\\Python36‘, ‘C:\\Python36\\lib\\site-packages‘]

Note: The exact contents of sys.path are installation-dependent. The above will almost certainly look slightly different on your computer.

Thus, to ensure your module is found, you need to do one of the following :

- Put

mod.pyin the directory where the input script is located or the current directory, if interactive - Modify the

PYTHONPATHenvironment variable to contain the directory wheremod.pyis located before starting the interpreter- Or: Put

mod.pyin one of the directories already contained in thePYTHONPATHvariable

- Or: Put

- Put

mod.pyin one of the installation-dependent directories, which you may or may not have write-access to, depending on the OS

There is actually one additional option: you can put the module file in any directory of your choice and then modify sys.path at run-time so that it contains that directory. For example, in this case, you could put mod.py in directory C:\Users\john and then issue the following statements :

>>> sys.path.append(r‘C:\Users\john‘)

>>> sys.path

[‘‘, ‘C:\\Users\\john\\Documents\\Python\\doc‘, ‘C:\\Python36\\Lib\\idlelib‘,

‘C:\\Python36\\python36.zip‘, ‘C:\\Python36\\DLLs‘, ‘C:\\Python36\\lib‘,

‘C:\\Python36‘, ‘C:\\Python36\\lib\\site-packages‘, ‘C:\\Users\\john‘]

>>> import mod

Once a module has been imported, you can determine the location where it was found with the module’s __file__ attribute:

>>> import mod

>>> mod.__file__

‘C:\\Users\\john\\mod.py‘

>>> import re

>>> re.__file__

‘C:\\Python36\\lib\\re.py‘

The directory portion of __file__ should be one of the directories in sys.path.

The import Statement

Module contents are made available to the caller with the import statement. The importstatement takes many different forms, shown below.

import <module_name>

The simplest form is the one already shown above:

import <module_name>

Note that this does not make the module contents directly accessible to the caller. Each module has its own private symbol table, which serves as the global symbol table for all objects defined in the module. Thus, a module creates a separate namespace, as already noted.

The statement import <module_name> only places <module_name> in the caller’s symbol table. The objects that are defined in the module remain in the module’s private symbol table.

From the caller, objects in the module are only accessible when prefixed with <module_name> via dot notation, as illustrated below.

After the following import statement, mod is placed into the local symbol table. Thus, modhas meaning in the caller’s local context:

>>> import mod

>>> mod

<module ‘mod‘ from ‘C:\\Users\\john\\Documents\\Python\\doc\\mod.py‘>

But s and foo remain in the module’s private symbol table and are not meaningful in the local context:

>>> s

NameError: name ‘s‘ is not defined

>>> foo(‘quux‘)

NameError: name ‘foo‘ is not defined

To be accessed in the local context, names of objects defined in the module must be prefixed by mod:

>>> mod.s

‘If Comrade Napoleon says it, it must be right.‘

>>> mod.foo(‘quux‘)

arg = quux

Several comma-separated modules may be specified in a single import statement:

import <module_name>[, <module_name> ...]

from <module_name> import <name(s)>

An alternate form of the import statement allows individual objects from the module to be imported directly into the caller’s symbol table:

from <module_name> import <name(s)>

Following execution of the above statement, <name(s)> can be referenced in the caller’s environment without the <module_name> prefix:

>>> from mod import s, foo

>>> s

‘If Comrade Napoleon says it, it must be right.‘

>>> foo(‘quux‘)

arg = quux

>>> from mod import Foo

>>> x = Foo()

>>> x

<mod.Foo object at 0x02E3AD50>

Because this form of import places the object names directly into the caller’s symbol table, any objects that already exist with the same name will be overwritten:

>>> a = [‘foo‘, ‘bar‘, ‘baz‘]

>>> a

[‘foo‘, ‘bar‘, ‘baz‘]

>>> from mod import a

>>> a

[100, 200, 300]

It is even possible to indiscriminately import everything from a module at one fell swoop:

from <module_name> import *

This will place the names of all objects from <module_name> into the local symbol table, with the exception of any that begin with the underscore (_) character.

For example:

>>> from mod import *

>>> s

‘If Comrade Napoleon says it, it must be right.‘

>>> a

[100, 200, 300]

>>> foo

<function foo at 0x03B449C0>

>>> Foo

<class ‘mod.Foo‘>

This isn’t necessarily recommended in large-scale production code. It’s a bit dangerous because you are entering names into the local symbol table en masse. Unless you know them all well and can be confident there won’t be a conflict, you have a decent chance of overwriting an existing name inadvertently. However, this syntax is quite handy when you are just mucking around with the interactive interpreter, for testing or discovery purposes, because it quickly gives you access to everything a module has to offer without a lot of typing.

from <module_name> import <name> as <alt_name>

It is also possible to import individual objects but enter them into the local symbol table with alternate names:

from <module_name> import <name> as <alt_name>[, <name> as <alt_name> …]

This makes it possible to place names directly into the local symbol table but avoid conflicts with previously existing names:

>>> s = ‘foo‘

>>> a = [‘foo‘, ‘bar‘, ‘baz‘]

>>> from mod import s as string, a as alist

>>> s

‘foo‘

>>> string

‘If Comrade Napoleon says it, it must be right.‘

>>> a

[‘foo‘, ‘bar‘, ‘baz‘]

>>> alist

[100, 200, 300]

import <module_name> as <alt_name>

You can also import an entire module under an alternate name:

import <module_name> as <alt_name>

>>> import mod as my_module

>>> my_module.a

[100, 200, 300]

>>> my_module.foo(‘qux‘)

arg = qux

Module contents can be imported from within a function definition. In that case(swywx), the importdoes not occur until the function is called:

>>> def bar():

... from mod import foo

... foo(‘corge‘)

...

>>> bar()

arg = corge

However, Python 3 does not allow the indiscriminate import * syntax from within a function:

>>> def bar():

... from mod import *

...

SyntaxError: import * only allowed at module level

Lastly, a try statement with an except ImportError clause can be used to guard against unsuccessful import attempts:

>>> try:

... # Non-existent module

... import baz

... except ImportError:

... print(‘Module not found‘)

...

Module not found

>>> try:

... # Existing module, but non-existent object

... from mod import baz

... except ImportError:

... print(‘Object not found in module‘)

...

Object not found in module

The dir() Function

The built-in function dir() returns a list of defined names in a namespace. Without arguments, it produces an alphabetically sorted list of names in the current local symbol table:

>>> dir()

[‘__annotations__‘, ‘__builtins__‘, ‘__doc__‘, ‘__loader__‘, ‘__name__‘,

‘__package__‘, ‘__spec__‘]

>>> qux = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

>>> dir()

[‘__annotations__‘, ‘__builtins__‘, ‘__doc__‘, ‘__loader__‘, ‘__name__‘,

‘__package__‘, ‘__spec__‘, ‘qux‘]

>>> class Bar():

... pass

...

>>> x = Bar()

>>> dir()

[‘Bar‘, ‘__annotations__‘, ‘__builtins__‘, ‘__doc__‘, ‘__loader__‘, ‘__name__‘,

‘__package__‘, ‘__spec__‘, ‘qux‘, ‘x‘]

Note how the first call to dir() above lists several names that are automatically defined and already in the namespace when the interpreter starts. As new names are defined (qux, Bar, x), they appear on subsequent invocations of dir().

This can be useful for identifying what exactly has been added to the namespace by an import statement:

>>> dir()

[‘__annotations__‘, ‘__builtins__‘, ‘__doc__‘, ‘__loader__‘, ‘__name__‘,

‘__package__‘, ‘__spec__‘]

>>> import mod

>>> dir()

[‘__annotations__‘, ‘__builtins__‘, ‘__doc__‘, ‘__loader__‘, ‘__name__‘,

‘__package__‘, ‘__spec__‘, ‘mod‘]

>>> mod.s

‘If Comrade Napoleon says it, it must be right.‘

>>> mod.foo([1, 2, 3])

arg = [1, 2, 3]

>>> from mod import a, Foo

>>> dir()

[‘Foo‘, ‘__annotations__‘, ‘__builtins__‘, ‘__doc__‘, ‘__loader__‘, ‘__name__‘,

‘__package__‘, ‘__spec__‘, ‘a‘, ‘mod‘]

>>> a

[100, 200, 300]

>>> x = Foo()

>>> x

<mod.Foo object at 0x002EAD50>

>>> from mod import s as string

>>> dir()

[‘Foo‘, ‘__annotations__‘, ‘__builtins__‘, ‘__doc__‘, ‘__loader__‘, ‘__name__‘,

‘__package__‘, ‘__spec__‘, ‘a‘, ‘mod‘, ‘string‘, ‘x‘]

>>> string

‘If Comrade Napoleon says it, it must be right.‘

When given an argument that is the name of a module, dir() lists the names defined in the module:

>>> import mod

>>> dir(mod)

[‘Foo‘, ‘__builtins__‘, ‘__cached__‘, ‘__doc__‘, ‘__file__‘, ‘__loader__‘,

‘__name__‘, ‘__package__‘, ‘__spec__‘, ‘a‘, ‘foo‘, ‘s‘]

>>> dir()

[‘__annotations__‘, ‘__builtins__‘, ‘__doc__‘, ‘__loader__‘, ‘__name__‘,

‘__package__‘, ‘__spec__‘]

>>> from mod import *

>>> dir()

[‘Foo‘, ‘__annotations__‘, ‘__builtins__‘, ‘__doc__‘, ‘__loader__‘, ‘__name__‘,

‘__package__‘, ‘__spec__‘, ‘a‘, ‘foo‘, ‘s‘]

Executing a Module as a Script

Any .py file that contains a module is essentially also a Python script, and there isn’t any reason it can’t be executed like one.

Here again is mod.py as it was defined above:

mod.py

s = "If Comrade Napoleon says it, it must be right."

a = [100, 200, 300]

def foo(arg):

print(f‘arg = {arg}‘)

class Foo:

pass

This can be run as a script:

C:\Users\john\Documents>python mod.py

C:\Users\john\Documents>

There are no errors, so it apparently worked. Granted, it’s not very interesting. As it is written, it only defines objects. It doesn’t do anything with them, and it doesn’t generate any output.

Let’s modify the above Python module so it does generate some output when run as a script:

mod.py

s = "If Comrade Napoleon says it, it must be right."

a = [100, 200, 300]

def foo(arg):

print(f‘arg = {arg}‘)

class Foo:

pass

print(s)

print(a)

foo(‘quux‘)

x = Foo()

print(x)

Now it should be a little more interesting:

C:\Users\john\Documents>python mod.py

If Comrade Napoleon says it, it must be right.

[100, 200, 300]

arg = quux

<__main__.Foo object at 0x02F101D0>

Unfortunately, now it also generates output when imported as a module:

>>> import mod

If Comrade Napoleon says it, it must be right.

[100, 200, 300]

arg = quux

<mod.Foo object at 0x0169AD50>

This is probably not what you want. It isn’t usual for a module to generate output when it is imported.

Wouldn’t it be nice if you could distinguish between when the file is loaded as a module and when it is run as a standalone script?

Ask and ye shall receive.

When a .py file is imported as a module, Python sets the special dunder variable __name__to the name of the module. However, if a file is run as a standalone script, __name__ is (creatively) set to the string ‘__main__‘. Using this fact, you can discern which is the case at run-time and alter behavior accordingly:

mod.py

s = "If Comrade Napoleon says it, it must be right."

a = [100, 200, 300]

def foo(arg):

print(f‘arg = {arg}‘)

class Foo:

pass

if (__name__ == ‘__main__‘):

print(‘Executing as standalone script‘)

print(s)

print(a)

foo(‘quux‘)

x = Foo()

print(x)

Now, if you run as a script, you get output:

C:\Users\john\Documents>python mod.py

Executing as standalone script

If Comrade Napoleon says it, it must be right.

[100, 200, 300]

arg = quux

<__main__.Foo object at 0x03450690>

But if you import as a module, you don’t:

>>> import mod

>>> mod.foo(‘grault‘)

arg = grault

Modules are often designed with the capability to run as a standalone script for purposes of testing the functionality that is contained within the module. This is referred to as unit testing. For example, suppose you have created a module fact.py containing a factorialfunction, as follows:

fact.py

def fact(n):

return 1 if n == 1 else n * fact(n-1)

if (__name__ == ‘__main__‘):

import sys

if len(sys.argv) > 1:

print(fact(int(sys.argv[1])))

The file can be treated as a module, and the fact() function imported:

>>> from fact import fact

>>> fact(6)

720

But it can also be run as a standalone by passing an integer argument on the command-line for testing:

C:\Users\john\Documents>python fact.py 6

720

Reloading a Module

For reasons of efficiency, a module is only loaded once per interpreter session. That is fine for function and class definitions, which typically make up the bulk of a module’s contents. But a module can contain executable statements as well, usually for initialization. Be aware that these statements will only be executed the first time a module is imported.

Consider the following file mod.py:

mod.py

a = [100, 200, 300]

print(‘a =‘, a)

>>> import mod

a = [100, 200, 300]

>>> import mod

>>> import mod

>>> mod.a

[100, 200, 300]

The print() statement is not executed on subsequent imports. (For that matter, neither is the assignment statement, but as the final display of the value of mod.a shows, that doesn’t matter. Once the assignment is made, it sticks.)

If you make a change to a module and need to reload it, you need to either restart the interpreter or use a function called reload() from module importlib:

>>> import mod

a = [100, 200, 300]

>>> import mod

>>> import importlib

>>> importlib.reload(mod)

a = [100, 200, 300]

<module ‘mod‘ from ‘C:\\Users\\john\\Documents\\Python\\doc\\mod.py‘>

Python Packages

Suppose you have developed a very large application that includes many modules. As the number of modules grows, it becomes difficult to keep track of them all if they are dumped into one location. This is particularly so if they have similar names or functionality. You might wish for a means of grouping and organizing them.

Packages allow for a hierarchical structuring of the module namespace using dot notation. In the same way that modules help avoid collisions between global variable names, packages help avoid collisions between module names.

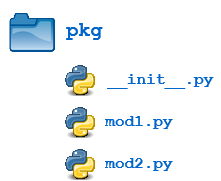

Creating a package is quite straightforward, since it makes use of the operating system’s inherent hierarchical file structure. Consider the following arrangement:

Here, there is a directory named pkg that contains two modules, mod1.py and mod2.py. The contents of the modules are:

mod1.py

def foo():

print(‘[mod1] foo()‘)

class Foo:

pass

mod2.py

def bar():

print(‘[mod2] bar()‘)

class Bar:

pass

Given this structure, if the pkg directory resides in a location where it can be found (in one of the directories contained in sys.path), you can refer to the two modules with dot notation(pkg.mod1, pkg.mod2) and import them with the syntax you are already familiar with:

import <module_name>[, <module_name> ...]

>>> import pkg.mod1, pkg.mod2

>>> pkg.mod1.foo()

[mod1] foo()

>>> x = pkg.mod2.Bar()

>>> x

<pkg.mod2.Bar object at 0x033F7290>

from <module_name> import <name(s)>

>>> from pkg.mod1 import foo

>>> foo()

[mod1] foo()

from <module_name> import <name> as <alt_name>

>>> from pkg.mod2 import Bar as Qux

>>> x = Qux()

>>> x

<pkg.mod2.Bar object at 0x036DFFD0>

You can import modules with these statements as well:

from <package_name> import <modules_name>[, <module_name> ...]

from <package_name> import <module_name> as <alt_name>

>>> from pkg import mod1

>>> mod1.foo()

[mod1] foo()

>>> from pkg import mod2 as quux

>>> quux.bar()

[mod2] bar()

You can technically import the package as well:

>>> import pkg

>>> pkg

<module ‘pkg‘ (namespace)>

But this is of little avail. Though this is, strictly speaking, a syntactically correct Python statement, it doesn’t do much of anything useful. In particular, it does not place any of the modules in pkg into the local namespace:

>>> pkg.mod1

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<pyshell#34>", line 1, in <module>

pkg.mod1

AttributeError: module ‘pkg‘ has no attribute ‘mod1‘

>>> pkg.mod1.foo()

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<pyshell#35>", line 1, in <module>

pkg.mod1.foo()

AttributeError: module ‘pkg‘ has no attribute ‘mod1‘

>>> pkg.mod2.Bar()

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<pyshell#36>", line 1, in <module>

pkg.mod2.Bar()

AttributeError: module ‘pkg‘ has no attribute ‘mod2‘

To actually import the modules or their contents, you need to use one of the forms shown above.

Package Initialization

If a file named __init__.py is present in a package directory, it is invoked when the package or a module in the package is imported. This can be used for execution of package initialization code, such as initialization of package-level data.

For example, consider the following __init__.py file:

__init__.py

print(f‘Invoking __init__.py for {__name__}‘)

A = [‘quux‘, ‘corge‘, ‘grault‘]

Let’s add this file to the pkg directory from the above example:

Now when the package is imported, global list A is initialized:

>>> import pkg

Invoking __init__.py for pkg

>>> pkg.A

[‘quux‘, ‘corge‘, ‘grault‘]

A module in the package can access the global by importing it in turn:

mod1.py

def foo():

from pkg import A

print(‘[mod1] foo() / A = ‘, A)

class Foo:

pass

>>> from pkg import mod1

Invoking __init__.py for pkg

>>> mod1.foo()

[mod1] foo() / A = [‘quux‘, ‘corge‘, ‘grault‘]

__init__.py can also be used to effect automatic importing of modules from a package. For example, earlier you saw that the statement import pkg only places the name pkg in the caller’s local symbol table and doesn’t import any modules. But if __init__.py in the pkgdirectory contains the following:

__init__.py

print(f‘Invoking __init__.py for {__name__}‘)

import pkg.mod1, pkg.mod2

then when you execute import pkg, modules mod1 and mod2 are imported automatically:

>>> import pkg

Invoking __init__.py for pkg

>>> pkg.mod1.foo()

[mod1] foo()

>>> pkg.mod2.bar()

[mod2] bar()

Note: Much of the Python documentation states that an __init__.py file must be present in the package directory when creating a package. This was once true. It used to be that the very presence of __init__.py signified to Python that a package was being defined. The file could contain initialization code or even be empty, but it had to be present.

Starting with Python 3.3, Implicit Namespace Packages were introduced. These allow for the creation of a package without any __init__.py file. Of course, it can still be present if package initialization is needed. But it is no longer required.

Importing * From a Package

For the purposes of the following discussion, the previously defined package is expanded to contain some additional modules:

There are now four modules defined in the pkg directory. Their contents are as shown below:

mod1.py

def foo():

print(‘[mod1] foo()‘)

class Foo:

pass

mod2.py

def bar():

print(‘[mod2] bar()‘)

class Bar:

pass

mod3.py

def baz():

print(‘[mod3] baz()‘)

class Baz:

pass

mod4.py

def qux():

print(‘[mod4] qux()‘)

class Qux:

pass

(Imaginative, aren’t they?)

You have already seen that when import * is used for a module, all objects from the module are imported into the local symbol table, except those whose names begin with an underscore, as always:

>>> dir()

[‘__annotations__‘, ‘__builtins__‘, ‘__doc__‘, ‘__loader__‘, ‘__name__‘,

‘__package__‘, ‘__spec__‘]

>>> from pkg.mod3 import *

>>> dir()

[‘Baz‘, ‘__annotations__‘, ‘__builtins__‘, ‘__doc__‘, ‘__loader__‘, ‘__name__‘,

‘__package__‘, ‘__spec__‘, ‘baz‘]

>>> baz()

[mod3] baz()

>>> Baz

<class ‘pkg.mod3.Baz‘>

The analogous statement for a package is this:

from <package_name> import *

What does that do?

>>> dir()

[‘__annotations__‘, ‘__builtins__‘, ‘__doc__‘, ‘__loader__‘, ‘__name__‘,

‘__package__‘, ‘__spec__‘]

>>> from pkg import *

>>> dir()

[‘__annotations__‘, ‘__builtins__‘, ‘__doc__‘, ‘__loader__‘, ‘__name__‘,

‘__package__‘, ‘__spec__‘]

Hmph. Not much. You might have expected (assuming you had any expectations at all) that Python would dive down into the package directory, find all the modules it could, and import them all. But as you can see, by default that is not what happens.

Instead, Python follows this convention: if the __init__.py file in the package directory contains a list named __all__, it is taken to be a list of modules that should be imported when the statement from <package_name> import * is encountered.

For the present example, suppose you create an __init__.py in the pkg directory like this:

pkg/__init__.py

__all__ = [

‘mod1‘,

‘mod2‘,

‘mod3‘,

‘mod4‘

]

Now from pkg import * imports all four modules:

>>> dir()

[‘__annotations__‘, ‘__builtins__‘, ‘__doc__‘, ‘__loader__‘, ‘__name__‘,

‘__package__‘, ‘__spec__‘]

>>> from pkg import *

>>> dir()

[‘__annotations__‘, ‘__builtins__‘, ‘__doc__‘, ‘__loader__‘, ‘__name__‘,

‘__package__‘, ‘__spec__‘, ‘mod1‘, ‘mod2‘, ‘mod3‘, ‘mod4‘]

>>> mod2.bar()

[mod2] bar()

>>> mod4.Qux

<class ‘pkg.mod4.Qux‘>

Using import * still isn’t considered terrific form, any more for packages than for modules. But this facility at least gives the creator of the package some control over what happens when import * is specified. (In fact, it provides the capability to disallow it entirely, simply by declining to define __all__ at all. As you have seen, the default behavior for packages is to import nothing.)

By the way, __all__ can be defined in a module as well and serves the same purpose: to control what is imported with import *. For example, modify mod1.py as follows:

pkg/mod1.py

__all__ = [‘foo‘]

def foo():

print(‘[mod1] foo()‘)

class Foo:

pass

Now an import * statement from pkg.mod1 will only import what is contained in __all__:

>>> dir()

[‘__annotations__‘, ‘__builtins__‘, ‘__doc__‘, ‘__loader__‘, ‘__name__‘,

‘__package__‘, ‘__spec__‘]

>>> from pkg.mod1 import *

>>> dir()

[‘__annotations__‘, ‘__builtins__‘, ‘__doc__‘, ‘__loader__‘, ‘__name__‘,

‘__package__‘, ‘__spec__‘, ‘foo‘]

>>> foo()

[mod1] foo()

>>> Foo

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<pyshell#37>", line 1, in <module>

Foo

NameError: name ‘Foo‘ is not defined

foo() (the function) is now defined in the local namespace, but Foo (the class) is not, because the latter is not in __all__.

In summary, __all__ is used by both packages and modules to control what is imported when import * is specified. But the default behavior differs:

- For a package, when

__all__is not defined,import *does not import anything. - For a module, when

__all__is not defined,import *imports everything (except—you guessed it—names starting with an underscore).

Subpackages

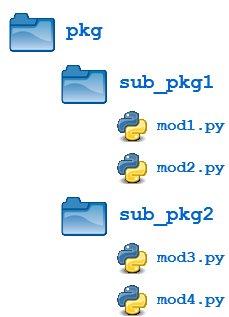

Packages can contain nested subpackages to arbitrary depth. For example, let’s make one more modification to the example package directory as follows:

The four modules (mod1.py, mod2.py, mod3.py and mod4.py) are defined as previously. But now, instead of being lumped together into the pkg directory, they are split out into two subpackage directories, sub_pkg1 and sub_pkg2.

Importing still works the same as shown previously. Syntax is similar, but additional dot notation is used to separate package name from subpackage name:

>>> import pkg.sub_pkg1.mod1

>>> pkg.sub_pkg1.mod1.foo()

[mod1] foo()

>>> from pkg.sub_pkg1 import mod2

>>> mod2.bar()

[mod2] bar()

>>> from pkg.sub_pkg2.mod3 import baz

>>> baz()

[mod3] baz()

>>> from pkg.sub_pkg2.mod4 import qux as grault

>>> grault()

[mod4] qux()

In addition, a module in one subpackage can reference objects in a sibling subpackage (in the event that the sibling contains some functionality that you need). For example, suppose you want to import and execute function foo() (defined in module mod1) from within module mod3. You can either use an absolute import:

pkg/sub__pkg2/mod3.py

def baz():

print(‘[mod3] baz()‘)

class Baz:

pass

from pkg.sub_pkg1.mod1 import foo

foo()

>>> from pkg.sub_pkg2 import mod3

[mod1] foo()

>>> mod3.foo()

[mod1] foo()

Or you can use a relative import, where .. refers to the package one level up. From within mod3.py, which is in subpackage sub_pkg2,

..evaluates to the parent package (pkg), and..sub_pkg1evaluates to subpackagesub_pkg1of the parent package.

pkg/sub__pkg2/mod3.py

def baz():

print(‘[mod3] baz()‘)

class Baz:

pass

from .. import sub_pkg1

print(sub_pkg1)

from ..sub_pkg1.mod1 import foo

foo()

>>> from pkg.sub_pkg2 import mod3

<module ‘pkg.sub_pkg1‘ (namespace)>

[mod1] foo()

Conclusion

In this tutorial, you covered the following topics:

- How to create a Python module

- Locations where the Python interpreter searches for a module

- How to obtain access to the objects defined in a module with the

importstatement - How to create a module that is executable as a standalone script

- How to organize modules into packages and subpackages

- How to control package initialization

Free PDF Download: Python 3 Cheat Sheet

This will hopefully allow you to better understand how to gain access to the functionality available in the many third-party and built-in modules available in Python.

Additionally, if you are developing your own application, creating your own modules and packages will help you organize and modularize your code, which makes coding, maintenance, and debugging easier.

If you want to learn more, check out the following documentation at Python.org:

Happy Pythoning!