标签:

目前python 提供了几种多线程实现方式 thread,threading,multithreading ,其中thread模块比较底层,而threading模块是对thread做了一些包装,可以更加方便的被使用。

2.7版本之前python对线程的支持还不够完善,不能利用多核CPU,但是2.7版本的python中已经考虑改进这点,出现了multithreading 模块。threading模块里面主要是对一些线程的操作对象化,创建Thread的class。一般来说,使用线程有两种模式:

A 创建线程要执行的函数,把这个函数传递进Thread对象里,让它来执行;

B 继承Thread类,创建一个新的class,将要执行的代码 写到run函数里面。

本文介绍两种实现方法。

第一种 创建函数并且传入Thread 对象中

t.py 脚本内容

执行结果:

thclass.py 脚本内容:

执行结果:

单线程

在好些年前的MS-DOS时代,操作系统处理问题都是单任务的,我想做听音乐和看电影两件事儿,那么一定要先排一下顺序。

(好吧!我们不纠结在DOS时代是否有听音乐和看影的应用。^_^)

from time import ctime,sleep

def music():

for i in range(2):

print "I was listening to music. %s" %ctime()

sleep(1)

def move():

for i in range(2):

print "I was at the movies! %s" %ctime()

sleep(5)

if __name__ == ‘__main__‘:

music()

move()

print "all over %s" %ctime()

我们先听了一首音乐,通过for循环来控制音乐的播放了两次,每首音乐播放需要1秒钟,sleep()来控制音乐播放的时长。接着我们又看了一场电影,

每一场电影需要5秒钟,因为太好看了,所以我也通过for循环看两遍。在整个休闲娱乐活动结束后,我通过

print "all over %s" %ctime()

看了一下当前时间,差不多该睡觉了。

运行结果:

>>=========================== RESTART ================================

>>>

I was listening to music. Thu Apr 17 10:47:08 2014

I was listening to music. Thu Apr 17 10:47:09 2014

I was at the movies! Thu Apr 17 10:47:10 2014

I was at the movies! Thu Apr 17 10:47:15 2014

all over Thu Apr 17 10:47:20 2014

其实,music()和move()更应该被看作是音乐和视频播放器,至于要播放什么歌曲和视频应该由我们使用时决定。所以,我们对上面代码做了改造:

#coding=utf-8

import threading

from time import ctime,sleep

def music(func):

for i in range(2):

print "I was listening to %s. %s" %(func,ctime())

sleep(1)

def move(func):

for i in range(2):

print "I was at the %s! %s" %(func,ctime())

sleep(5)

if __name__ == ‘__main__‘:

music(u‘爱情买卖‘)

move(u‘阿凡达‘)

print "all over %s" %ctime()

对music()和move()进行了传参处理。体验中国经典歌曲和欧美大片文化。

运行结果:

>>> ======================== RESTART ================================

>>>

I was listening to 爱情买卖. Thu Apr 17 11:48:59 2014

I was listening to 爱情买卖. Thu Apr 17 11:49:00 2014

I was at the 阿凡达! Thu Apr 17 11:49:01 2014

I was at the 阿凡达! Thu Apr 17 11:49:06 2014

all over Thu Apr 17 11:49:11 2014

多线程

科技在发展,时代在进步,我们的CPU也越来越快,CPU抱怨,P大点事儿占了我一定的时间,其实我同时干多个活都没问题的;于是,操作系统就进入了多任务时代。我们听着音乐吃着火锅的不在是梦想。

python提供了两个模块来实现多线程thread 和threading ,thread 有一些缺点,在threading 得到了弥补,为了不浪费你和时间,所以我们直接学习threading 就可以了。

继续对上面的例子进行改造,引入threadring来同时播放音乐和视频:

#coding=utf-8

import threading

from time import ctime,sleep

def music(func):

for i in range(2):

print "I was listening to %s. %s" %(func,ctime())

sleep(1)

def move(func):

for i in range(2):

print "I was at the %s! %s" %(func,ctime())

sleep(5)

threads = []

t1 = threading.Thread(target=music,args=(u‘爱情买卖‘,))

threads.append(t1)

t2 = threading.Thread(target=move,args=(u‘阿凡达‘,))

threads.append(t2)

if __name__ == ‘__main__‘:

for t in threads:

t.setDaemon(True)

t.start()

print "all over %s" %ctime()

import threading

首先导入threading 模块,这是使用多线程的前提。

threads = []

t1 = threading.Thread(target=music,args=(u‘爱情买卖‘,))

threads.append(t1)

创建了threads数组,创建线程t1,使用threading.Thread()方法,在这个方法中调用music方法target=music,args方法对music进行传参。 把创建好的线程t1装到threads数组中。

接着以同样的方式创建线程t2,并把t2也装到threads数组。

for t in threads:

t.setDaemon(True)

t.start()

最后通过for循环遍历数组。(数组被装载了t1和t2两个线程)

setDaemon()

setDaemon(True)将线程声明为守护线程,必须在start() 方法调用之前设置,如果不设置为守护线程程序会被无限挂起。子线程启动后,父线程也继续执行下去,当父线程执行完最后一条语句print "all over %s" %ctime()后,没有等待子线程,直接就退出了,同时子线程也一同结束。

start()

开始线程活动。

运行结果:

>>> ========================= RESTART ================================

>>>

I was listening to 爱情买卖. Thu Apr 17 12:51:45 2014 I was at the 阿凡达! Thu Apr 17 12:51:45 2014 all over Thu Apr 17 12:51:45 2014

从执行结果来看,子线程(muisc 、move )和主线程(print "all over %s" %ctime())都是同一时间启动,但由于主线程执行完结束,所以导致子线程也终止。

继续调整程序:

...

if __name__ == ‘__main__‘:

for t in threads:

t.setDaemon(True)

t.start()

t.join()

print "all over %s" %ctime()

我们只对上面的程序加了个join()方法,用于等待线程终止。join()的作用是,在子线程完成运行之前,这个子线程的父线程将一直被阻塞。

注意: join()方法的位置是在for循环外的,也就是说必须等待for循环里的两个进程都结束后,才去执行主进程。

运行结果:

>>> ========================= RESTART ================================

>>>

I was listening to 爱情买卖. Thu Apr 17 13:04:11 2014 I was at the 阿凡达! Thu Apr 17 13:04:11 2014

I was listening to 爱情买卖. Thu Apr 17 13:04:12 2014

I was at the 阿凡达! Thu Apr 17 13:04:16 2014

all over Thu Apr 17 13:04:21 2014

从执行结果可看到,music 和move 是同时启动的。

开始时间4分11秒,直到调用主进程为4分22秒,总耗时为10秒。从单线程时减少了2秒,我们可以把music的sleep()的时间调整为4秒。

...

def music(func):

for i in range(2):

print "I was listening to %s. %s" %(func,ctime())

sleep(4)

...

执行结果:

>>> ====================== RESTART ================================

>>>

I was listening to 爱情买卖. Thu Apr 17 13:11:27 2014I was at the 阿凡达! Thu Apr 17 13:11:27 2014

I was listening to 爱情买卖. Thu Apr 17 13:11:31 2014

I was at the 阿凡达! Thu Apr 17 13:11:32 2014

all over Thu Apr 17 13:11:37 2014

子线程启动11分27秒,主线程运行11分37秒。

虽然music每首歌曲从1秒延长到了4 ,但通多程线的方式运行脚本,总的时间没变化。

本文从感性上让你快速理解python多线程的使用,更详细的使用请参考其它文档或资料。

==========================================================

class threading.Thread()说明:

class threading.Thread(group=None, target=None, name=None, args=(), kwargs={})

This constructor should always be called with keyword arguments. Arguments are:

group should be None; reserved for future extension when a ThreadGroup class is implemented.

target is the callable object to be invoked by the run() method. Defaults to None, meaning nothing is called.

name is the thread name. By default, a unique name is constructed of the form “Thread-N” where N is a small decimal number.

args is the argument tuple for the target invocation. Defaults to ().

kwargs is a dictionary of keyword arguments for the target invocation. Defaults to {}.

If the subclass overrides the constructor, it must make sure to invoke the base class constructor (Thread.__init__()) before doing

anything else to the thread.

Python代码代码的执行由python虚拟机(也叫解释器主循环)来控制。Python在设计之初就考虑到要在主循环中,同时只有一个线 程在执行,就像单CPU的系统中运行多个进程那样,内存中可以存放多个程序,但任意时候,只有一个程序在CPU中运行。同样,虽然python解释器可以 “运行”多个线程,但在任意时刻,只有一个线程在解释器中运行。

对python虚拟机的访问由全局解释器锁(GIL)来控制,这个GIL能保证同一时刻只有一个线程在运行。在多线程环境中,python虚拟机按以下方式执行:

1 设置GIL

2 切换到一个线程去运行

3 运行:(a.指定数量的字节码指令,或者b.线程主动让出控制(可以调用time.sleep()))

4 把线程设置为睡眠状态

5 解锁GIL

6 重复以上所有步骤

那么为什么要提出多线程呢?我们首先看一个单线程的例子。

from time import sleep,ctime

def loop0():

print ‘start loop 0 at:‘,ctime()

sleep(4)

print ‘loop 0 done at:‘,ctime()

def loop1():

print ‘start loop 1 at:‘,ctime()

sleep(2)

print ‘loop 1 done at:‘,ctime()

def main():

print ‘starting at:‘,ctime()

loop0()

loop1()

print ‘all DONE at:‘,ctime()

if __name__==‘__main__‘:

main()

运行结果:

>>>

starting at: Mon Aug 31 10:27:23 2009

start loop 0 at: Mon Aug 31 10:27:23 2009

loop 0 done at: Mon Aug 31 10:27:27 2009

start loop 1 at: Mon Aug 31 10:27:27 2009

loop 1 done at: Mon Aug 31 10:27:29 2009

all DONE at: Mon Aug 31 10:27:29 2009

>>>

可以看到单线程中的两个循环, 只有一个循环结束后另一个才开始。 总共用了6秒多的时间。假设两个loop中执行的不是sleep,而是一个别的运算的话,如果我们能让这些运算并行执行的话,是不是可以减少总的运行时间呢,这就是我们提出多线程的前提。

Python中的多线程模块:thread,threading,Queue。

1 thread ,这个模块一般不建议使用。下面我们直接把以上的例子改一下,演示一下。

from time import sleep,ctime

import thread

def loop0():

print ‘start loop 0 at:‘,ctime()

sleep(4)

print ‘loop 0 done at:‘,ctime()

def loop1():

print ‘start loop 1 at:‘,ctime()

sleep(2)

print ‘loop 1 done at:‘,ctime()

def main():

print ‘starting at:‘,ctime()

thread.start_new_thread(loop0,())

thread.start_new_thread(loop1,())

sleep(6)

print ‘all DONE at:‘,ctime()

if __name__==‘__main__‘:

main()

运行结果:

>>>

starting at: Mon Aug 31 11:04:39 2009

start loop 0 at: Mon Aug 31 11:04:39 2009

start loop 1 at: Mon Aug 31 11:04:39 2009

loop 1 done at: Mon Aug 31 11:04:41 2009

loop 0 done at: Mon Aug 31 11:04:43 2009

all DONE at: Mon Aug 31 11:04:45 2009

>>>

可以看到实际是运行了4秒两个loop就完成了。效率确实提高了。

2 threading模块

首先看一下threading模块中的对象:

Thread :表示一个线程的执行的对象

Lock :锁原语对象

RLock :可重入锁对象。使单线程可以再次获得已经获得的锁

Condition :条件变量对象能让一个线程停下来,等待其他线程满足了某个“条件”,如状态的改变或值的改变

Event :通用的条件变量。多个线程可以等待某个事件发生,在事件发生后,所有的线程都被激活

Semaphore :为等待锁的线程提供一个类似“等候室”的结构

BoundedSemaphore :与semaphore类似,只是它不允许超过初始值

Timer : 与Thread类似,只是,它要等待一段时间后才开始运行

其中Thread类是你主要的运行对象,它有很多函数,用它你可以用多种方法来创建线程,常用的为以下三种。

创建一个Thread的实例,传给它一个函数

创建一个Thread实例,传给它一个可调用的类对象

从Thread派生出一个子类,创建一个这个子类的实例

Thread类的函数有:

getName(self) 返回线程的名字

|

| isAlive(self) 布尔标志,表示这个线程是否还在运行中

|

| isDaemon(self) 返回线程的daemon标志

|

| join(self, timeout=None) 程序挂起,直到线程结束,如果给出timeout,则最多阻塞timeout秒

|

| run(self) 定义线程的功能函数

|

| setDaemon(self, daemonic) 把线程的daemon标志设为daemonic

|

| setName(self, name) 设置线程的名字

|

| start(self) 开始线程执行

下面看一个例子:(方法一:创建Thread实例,传递一个函数给它)

import threading

from time import sleep,ctime

loops=[4,2]

def loop(nloop,nsec):

print ‘start loop‘,nloop,‘at:‘,ctime()

sleep(nsec)

print ‘loop‘,nloop,‘done at:‘,ctime()

def main():

print ‘starting at:‘,ctime()

threads=[]

nloops=range(len(loops))

for i in nloops:

t=threading.Thread(target=loop,args=(i,loops[i]))

threads.append(t)

for i in nloops:

threads[i].start()

for i in nloops:

threads[i].join()

print ‘all done at:‘,ctime()

if __name__==‘__main__‘:

main()

可以看到第一个for循环,我们创建了两个线程,这里用到的是给Thread类传递了函数,把两个线程保存到threads列表中,第二个for循环是让两个线程开始执行。然后再让每个线程分别调用join函数,使程序挂起,直至两个线程结束。

另外的例子:(方法二:创建一个实例,传递一个可调用的类的对象)

import threading

from time import sleep,ctime

loops=[4,2]

class ThreadFunc(object):

def __init__(self,func,args,name=‘‘):

self.name=name

self.func=func

self.args=args

def __call__(self):

self.res=self.func(*self.args)

def loop(nloop,nsec):

print ‘start loop‘,nloop,‘at:‘,ctime()

sleep(nsec)

print ‘loop‘,nloop,‘done at:‘,ctime()

def main():

print ‘starting at:‘,ctime()

threads=[]

nloops=range(len(loops))

for i in nloops:

t=threading.Thread(target=ThreadFunc(loop,(i,loops[i]),loop.__name__))

threads.append(t)

for i in nloops:

threads[i].start()

for i in nloops:

threads[i].join()

print ‘all done at:‘,ctime()

if __name__==‘__main__‘:

main()

最后的方法:(方法三:创建一个这个子类的实例)

import threading

from time import sleep,ctime

loops=(4,2)

class MyThread(threading.Thread):

def __init__(self,func,args,name=‘‘):

threading.Thread.__init__(self)

self.name=name

self.func=func

self.args=args

def run(self):

apply(self.func,self.args)

def loop(nloop,nsec):

print ‘start loop‘,nloop,‘at:‘,ctime()

sleep(nsec)

print ‘loop‘,nloop,‘done at:‘,ctime()

def main():

print ‘starting at:‘,ctime()

threads=[]

nloops=range(len(loops))

for i in nloops:

t=MyThread(loop,(i,loops[i]),loop.__name__)

threads.append(t)

for i in nloops:

threads[i].start()

for i in nloops:

threads[i].join()

print ‘all done at:‘,ctime()

if __name__==‘__main__‘:

main()

另外我们可以把MyThread单独编成一个脚本模块,然后我们可以在别的程序里导入这个模块直接使用。

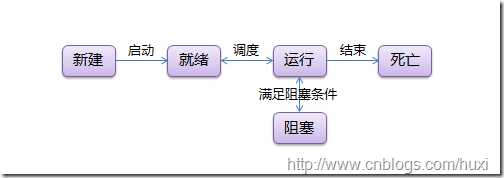

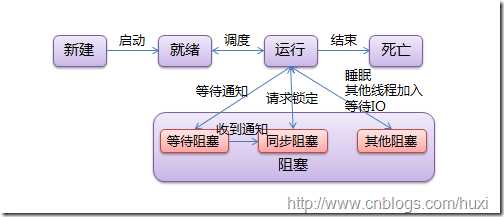

线程有5种状态,状态转换的过程如下图所示:

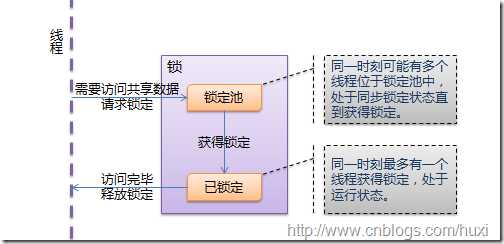

多 线程的优势在于可以同时运行多个任务(至少感觉起来是这样)。但是当线程需要共享数据时,可能存在数据不同步的问题。考虑这样一种情况:一个列表里所有元 素都是0,线程"set"从后向前把所有元素改成1,而线程"print"负责从前往后读取列表并打印。那么,可能线程"set"开始改的时候,线 程"print"便来打印列表了,输出就成了一半0一半1,这就是数据的不同步。为了避免这种情况,引入了锁的概念。

锁有两种状态—— 锁定和未锁定。每当一个线程比如"set"要访问共享数据时,必须先获得锁定;如果已经有别的线程比如"print"获得锁定了,那么就让线程"set" 暂停,也就是同步阻塞;等到线程"print"访问完毕,释放锁以后,再让线程"set"继续。经过这样的处理,打印列表时要么全部输出0,要么全部输出 1,不会再出现一半0一半1的尴尬场面。

线程与锁的交互如下图所示:

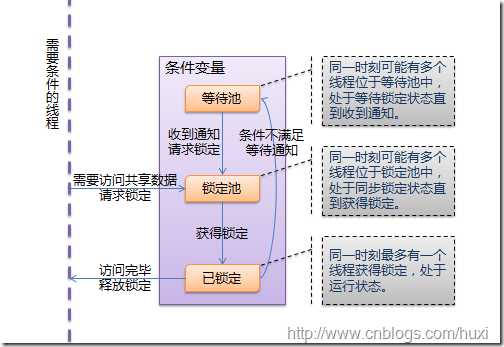

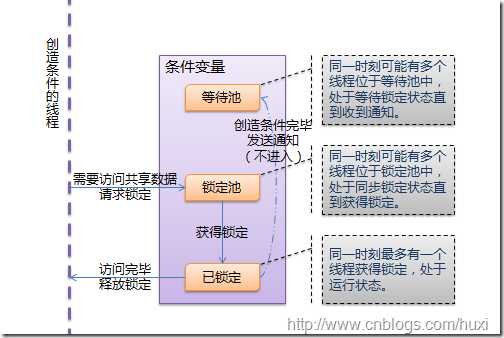

然 而还有另外一种尴尬的情况:列表并不是一开始就有的;而是通过线程"create"创建的。如果"set"或者"print" 在"create"还没有运行的时候就访问列表,将会出现一个异常。使用锁可以解决这个问题,但是"set"和"print"将需要一个无限循环——他们 不知道"create"什么时候会运行,让"create"在运行后通知"set"和"print"显然是一个更好的解决方案。于是,引入了条件变量。

条件变量允许线程比如"set"和"print"在条件不满足的时候(列表为None时)等待,等到条件满足的时候(列表已经创建)发出一个通知,告诉"set" 和"print"条件已经有了,你们该起床干活了;然后"set"和"print"才继续运行。

线程与条件变量的交互如下图所示:

最后看看线程运行和阻塞状态的转换。

阻塞有三种情况:

同步阻塞是指处于竞争锁定的状态,线程请求锁定时将进入这个状态,一旦成功获得锁定又恢复到运行状态;

等待阻塞是指等待其他线程通知的状态,线程获得条件锁定后,调用“等待”将进入这个状态,一旦其他线程发出通知,线程将进入同步阻塞状态,再次竞争条件锁定;

而其他阻塞是指调用time.sleep()、anotherthread.join()或等待IO时的阻塞,这个状态下线程不会释放已获得的锁定。

tips: 如果能理解这些内容,接下来的主题将是非常轻松的;并且,这些内容在大部分流行的编程语言里都是一样的。(意思就是非看懂不可 >_< 嫌作者水平低找别人的教程也要看懂)

Python通过两个标准库thread和threading提供对线程的支持。thread提供了低级别的、原始的线程以及一个简单的锁。

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

|

# encoding: UTF-8import threadimport time# 一个用于在线程中执行的函数def func(): for i in range(5): print ‘func‘ time.sleep(1) # 结束当前线程 # 这个方法与thread.exit_thread()等价 thread.exit() # 当func返回时,线程同样会结束 # 启动一个线程,线程立即开始运行# 这个方法与thread.start_new_thread()等价# 第一个参数是方法,第二个参数是方法的参数thread.start_new(func, ()) # 方法没有参数时需要传入空tuple# 创建一个锁(LockType,不能直接实例化)# 这个方法与thread.allocate_lock()等价lock = thread.allocate()# 判断锁是锁定状态还是释放状态print lock.locked()# 锁通常用于控制对共享资源的访问count = 0# 获得锁,成功获得锁定后返回True# 可选的timeout参数不填时将一直阻塞直到获得锁定# 否则超时后将返回Falseif lock.acquire(): count += 1 # 释放锁 lock.release()# thread模块提供的线程都将在主线程结束后同时结束time.sleep(6) |

thread 模块提供的其他方法:

thread.interrupt_main(): 在其他线程中终止主线程。

thread.get_ident(): 获得一个代表当前线程的魔法数字,常用于从一个字典中获得线程相关的数据。这个数字本身没有任何含义,并且当线程结束后会被新线程复用。

thread还提供了一个ThreadLocal类用于管理线程相关的数据,名为 thread._local,threading中引用了这个类。

由于thread提供的线程功能不多,无法在主线程结束后继续运行,不提供条件变量等等原因,一般不使用thread模块,这里就不多介绍了。

threading基于Java的线程模型设计。锁(Lock)和条件变量(Condition)在Java中是对象的基本行为(每一个对象都自带 了锁和条件变量),而在Python中则是独立的对象。Python Thread提供了Java Thread的行为的子集;没有优先级、线程组,线程也不能被停止、暂停、恢复、中断。Java Thread中的部分被Python实现了的静态方法在threading中以模块方法的形式提供。

threading 模块提供的常用方法:

threading.currentThread(): 返回当前的线程变量。

threading.enumerate(): 返回一个包含正在运行的线程的list。正在运行指线程启动后、结束前,不包括启动前和终止后的线程。

threading.activeCount(): 返回正在运行的线程数量,与len(threading.enumerate())有相同的结果。

threading模块提供的类:

Thread, Lock, Rlock, Condition, [Bounded]Semaphore, Event, Timer, local.

Thread是线程类,与Java类似,有两种使用方法,直接传入要运行的方法或从Thread继承并覆盖run():

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

|

# encoding: UTF-8import threading# 方法1:将要执行的方法作为参数传给Thread的构造方法def func(): print ‘func() passed to Thread‘t = threading.Thread(target=func)t.start()# 方法2:从Thread继承,并重写run()class MyThread(threading.Thread): def run(self): print ‘MyThread extended from Thread‘t = MyThread()t.start() |

构造方法:

Thread(group=None, target=None, name=None, args=(), kwargs={})

group: 线程组,目前还没有实现,库引用中提示必须是None;

target: 要执行的方法;

name: 线程名;

args/kwargs: 要传入方法的参数。

实例方法:

isAlive(): 返回线程是否在运行。正在运行指启动后、终止前。

get/setName(name): 获取/设置线程名。

is/setDaemon(bool): 获取/设置是否守护线程。初始值从创建该线程的线程继承。当没有非守护线程仍在运行时,程序将终止。

start(): 启动线程。

join([timeout]): 阻塞当前上下文环境的线程,直到调用此方法的线程终止或到达指定的timeout(可选参数)。

一个使用join()的例子:

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

|

# encoding: UTF-8import threadingimport timedef context(tJoin): print ‘in threadContext.‘ tJoin.start() # 将阻塞tContext直到threadJoin终止。 tJoin.join() # tJoin终止后继续执行。 print ‘out threadContext.‘def join(): print ‘in threadJoin.‘ time.sleep(1) print ‘out threadJoin.‘tJoin = threading.Thread(target=join)tContext = threading.Thread(target=context, args=(tJoin,))tContext.start() |

运行结果:

in threadContext.

in threadJoin.

out threadJoin.

out threadContext.

Lock(指令锁)是可用的最低级的同步指令。Lock处于锁定状态时,不被特定的线程拥有。Lock包含两种状态——锁定和非锁定,以及两个基本的方法。

可以认为Lock有一个锁定池,当线程请求锁定时,将线程至于池中,直到获得锁定后出池。池中的线程处于状态图中的同步阻塞状态。

构造方法:

Lock()

实例方法:

acquire([timeout]): 使线程进入同步阻塞状态,尝试获得锁定。

release(): 释放锁。使用前线程必须已获得锁定,否则将抛出异常。

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

|

# encoding: UTF-8import threadingimport timedata = 0lock = threading.Lock()def func(): global data print ‘%s acquire lock...‘ % threading.currentThread().getName() # 调用acquire([timeout])时,线程将一直阻塞, # 直到获得锁定或者直到timeout秒后(timeout参数可选)。 # 返回是否获得锁。 if lock.acquire(): print ‘%s get the lock.‘ % threading.currentThread().getName() data += 1 time.sleep(2) print ‘%s release lock...‘ % threading.currentThread().getName() # 调用release()将释放锁。 lock.release()t1 = threading.Thread(target=func)t2 = threading.Thread(target=func)t3 = threading.Thread(target=func)t1.start()t2.start()t3.start() |

RLock(可重入锁)是一个可以被同一个线程请求多次的同步指令。RLock使用了“拥有的线程”和“递归等级”的概念,处于锁定状态时,RLock被某个线程拥有。拥有RLock的线程可以再次调用acquire(),释放锁时需要调用release()相同次数。

可以认为RLock包含一个锁定池和一个初始值为0的计数器,每次成功调用 acquire()/release(),计数器将+1/-1,为0时锁处于未锁定状态。

构造方法:

RLock()

实例方法:

acquire([timeout])/release(): 跟Lock差不多。

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

|

# encoding: UTF-8import threadingimport timerlock = threading.RLock()def func(): # 第一次请求锁定 print ‘%s acquire lock...‘ % threading.currentThread().getName() if rlock.acquire(): print ‘%s get the lock.‘ % threading.currentThread().getName() time.sleep(2) # 第二次请求锁定 print ‘%s acquire lock again...‘ % threading.currentThread().getName() if rlock.acquire(): print ‘%s get the lock.‘ % threading.currentThread().getName() time.sleep(2) # 第一次释放锁 print ‘%s release lock...‘ % threading.currentThread().getName() rlock.release() time.sleep(2) # 第二次释放锁 print ‘%s release lock...‘ % threading.currentThread().getName() rlock.release()t1 = threading.Thread(target=func)t2 = threading.Thread(target=func)t3 = threading.Thread(target=func)t1.start()t2.start()t3.start() |

Condition(条件变量)通常与一个锁关联。需要在多个Contidion中共享一个锁时,可以传递一个Lock/RLock实例给构造方法,否则它将自己生成一个RLock实例。

可以认为,除了Lock带有的锁定池外,Condition还包含一个等待池,池中的线程处于状态图中的等待阻塞状态,直到另一个线程调用notify()/notifyAll()通知;得到通知后线程进入锁定池等待锁定。

构造方法:

Condition([lock/rlock])

实例方法:

acquire([timeout])/release(): 调用关联的锁的相应方法。

wait([timeout]): 调用这个方法将使线程进入Condition的等待池等待通知,并释放锁。使用前线程必须已获得锁定,否则将抛出异常。

notify(): 调用这个方法将从等待池挑选一个线程并通知,收到通知的线程将自动调用acquire()尝试获得锁定(进入锁定池);其他线程仍然在等待池中。调用这个方法不会释放锁定。使用前线程必须已获得锁定,否则将抛出异常。

notifyAll(): 调用这个方法将通知等待池中所有的线程,这些线程都将进入锁定池尝试获得锁定。调用这个方法不会释放锁定。使用前线程必须已获得锁定,否则将抛出异常。

例子是很常见的生产者/消费者模式:

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

|

# encoding: UTF-8import threadingimport time# 商品product = None# 条件变量con = threading.Condition()# 生产者方法def produce(): global product if con.acquire(): while True: if product is None: print ‘produce...‘ product = ‘anything‘ # 通知消费者,商品已经生产 con.notify() # 等待通知 con.wait() time.sleep(2)# 消费者方法def consume(): global product if con.acquire(): while True: if product is not None: print ‘consume...‘ product = None # 通知生产者,商品已经没了 con.notify() # 等待通知 con.wait() time.sleep(2)t1 = threading.Thread(target=produce)t2 = threading.Thread(target=consume)t2.start()t1.start() |

Semaphore(信号量)是计算机科学史上最古老的同步指令之一。Semaphore管理一个内置的计数器,每当调用acquire()时 -1,调用release() 时+1。计数器不能小于0;当计数器为0时,acquire()将阻塞线程至同步锁定状态,直到其他线程调用release()。

基于这个特点,Semaphore经常用来同步一些有“访客上限”的对象,比如连接池。

BoundedSemaphore 与Semaphore的唯一区别在于前者将在调用release()时检查计数器的值是否超过了计数器的初始值,如果超过了将抛出一个异常。

构造方法:

Semaphore(value=1): value是计数器的初始值。

实例方法:

acquire([timeout]): 请求Semaphore。如果计数器为0,将阻塞线程至同步阻塞状态;否则将计数器-1并立即返回。

release(): 释放Semaphore,将计数器+1,如果使用BoundedSemaphore,还将进行释放次数检查。release()方法不检查线程是否已获得 Semaphore。

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

|

# encoding: UTF-8import threadingimport time# 计数器初值为2semaphore = threading.Semaphore(2)def func(): # 请求Semaphore,成功后计数器-1;计数器为0时阻塞 print ‘%s acquire semaphore...‘ % threading.currentThread().getName() if semaphore.acquire(): print ‘%s get semaphore‘ % threading.currentThread().getName() time.sleep(4) # 释放Semaphore,计数器+1 print ‘%s release semaphore‘ % threading.currentThread().getName() semaphore.release()t1 = threading.Thread(target=func)t2 = threading.Thread(target=func)t3 = threading.Thread(target=func)t4 = threading.Thread(target=func)t1.start()t2.start()t3.start()t4.start()time.sleep(2)# 没有获得semaphore的主线程也可以调用release# 若使用BoundedSemaphore,t4释放semaphore时将抛出异常print ‘MainThread release semaphore without acquire‘semaphore.release() |

Event(事件)是最简单的线程通信机制之一:一个线程通知事件,其他线程等待事件。Event内置了一个初始为False的标志,当调用set()时设为True,调用clear()时重置为 False。wait()将阻塞线程至等待阻塞状态。

Event其实就是一个简化版的 Condition。Event没有锁,无法使线程进入同步阻塞状态。

构造方法:

Event()

实例方法:

isSet(): 当内置标志为True时返回True。

set(): 将标志设为True,并通知所有处于等待阻塞状态的线程恢复运行状态。

clear(): 将标志设为False。

wait([timeout]): 如果标志为True将立即返回,否则阻塞线程至等待阻塞状态,等待其他线程调用set()。

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

|

# encoding: UTF-8import threadingimport timeevent = threading.Event()def func(): # 等待事件,进入等待阻塞状态 print ‘%s wait for event...‘ % threading.currentThread().getName() event.wait() # 收到事件后进入运行状态 print ‘%s recv event.‘ % threading.currentThread().getName()t1 = threading.Thread(target=func)t2 = threading.Thread(target=func)t1.start()t2.start()time.sleep(2)# 发送事件通知print ‘MainThread set event.‘event.set() |

Timer(定时器)是Thread的派生类,用于在指定时间后调用一个方法。

构造方法:

Timer(interval, function, args=[], kwargs={})

interval: 指定的时间

function: 要执行的方法

args/kwargs: 方法的参数

实例方法:

Timer从Thread派生,没有增加实例方法。

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

|

# encoding: UTF-8import threadingdef func(): print ‘hello timer!‘timer = threading.Timer(5, func)timer.start() |

local是一个小写字母开头的类,用于管理 thread-local(线程局部的)数据。对于同一个local,线程无法访问其他线程设置的属性;线程设置的属性不会被其他线程设置的同名属性替换。

可以把local看成是一个“线程-属性字典”的字典,local封装了从自身使用线程作为 key检索对应的属性字典、再使用属性名作为key检索属性值的细节。

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

|

# encoding: UTF-8import threadinglocal = threading.local()local.tname = ‘main‘def func(): local.tname = ‘notmain‘ print local.tnamet1 = threading.Thread(target=func)t1.start()t1.join()print local.tname |

熟练掌握Thread、Lock、Condition就可以应对绝大多数需要使用线程的场合,某些情况下local也是非常有用的东西。本文的最后使用这几个类展示线程基础中提到的场景:

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

|

# encoding: UTF-8import threadingalist = Nonecondition = threading.Condition()def doSet(): if condition.acquire(): while alist is None: condition.wait() for i in range(len(alist))[::-1]: alist[i] = 1 condition.release()def doPrint(): if condition.acquire(): while alist is None: condition.wait() for i in alist: print i, print condition.release()def doCreate(): global alist if condition.acquire(): if alist is None: alist = [0 for i in range(10)] condition.notifyAll() condition.release()tset = threading.Thread(target=doSet,name=‘tset‘)tprint = threading.Thread(target=doPrint,name=‘tprint‘)tcreate = threading.Thread(target=doCreate,name=‘tcreate‘)tset.start()tprint.start()tcreate.start() |

Python多线程学习

一.创建线程

1.通过thread模块中的start_new_thread(func,args)创建线程:

在Eclipse+pydev中敲出以下代码:

运行报错如下:

网上查出原因是不建议使用thread,然后我在pythonGUI中做了测试,测试结果如下,显然python是支持thread创建多线程的,在pydev中出错原因暂时不明。

2.通过继承threading.Thread创建线程,以下示例创建了两个线程

3. 在threading.Thread中指定目标函数作为线程处理函数

二. threading.Thread中常用函数说明

| 函数名 |

功能 |

| run() | 如果采用方法2创建线程就需要重写该方法 |

| getName() | 获得线程的名称(方法2中有示例) |

| setName() | 设置线程的名称 |

| start() | 启动线程 |

| join(timeout) |

在join()位置等待另一线程结束后再继续运行join()后的操作,timeout是可选项,表示最大等待时间 |

| setDaemon(bool) |

True:当父线程结束时,子线程立即结束;False:父线程等待子线程结束后才结束。默认为False |

| isDaemon() | 判断子线程是否和父线程一起结束,即setDaemon()设置的值 |

| isAlive() |

判断线程是否在运行 |

以上方法中,我将对join()和setDaemon(bool)作着重介绍,示例如下:

(1)join方法:

这时的程序流程是:主线程先运行完,然后等待B线程运行,所以输出结果为:

如果启用t2.join() ,这时程序的运行流程是:当主线程运行到 t2.join() 时,它将等待 t2 运行完,然后再继续运行 t2.join() 后的操作,呵呵,你懂了吗,所以输出结果为:

(2)setDaemon方法:

这段代码的运行流程是:主线程打印完最后一句话后,等待son thread 运行完,然后程序才结束,所以输出结果为:

如果启用t.setDaemon(True) ,这段代码的运行流程是:当主线程打印完最后一句话后,不管 son thread 是否运行完,程序立即结束,所以输出结果为:

三. 小结

介绍到这里,python多线程使用级别的知识点已全部介绍完了,下面我会分析一下python多线程的同步问题。

一、Python中的线程使用:

Python中使用线程有两种方式:函数或者用类来包装线程对象。

1、 函数式:调用thread模块中的start_new_thread()函数来产生新线程。如下例:

上面的例子定义了一个线程函数timer,它打印出10条时间记录后退出,每次打印的间隔由interval参数决定。thread.start_new_thread(function, args[, kwargs])的第一个参数是线程函数(本例中的timer方法),第二个参数是传递给线程函数的参数,它必须是tuple类型,kwargs是可选参数。

线程的结束可以等待线程自然结束,也可以在线程函数中调用thread.exit()或thread.exit_thread()方法。

2、 创建threading.Thread的子类来包装一个线程对象,如下例:

就我个人而言,比较喜欢第二种方式,即创建自己的线程类,必要时重写threading.Thread类的方法,线程的控制可以由自己定制。

threading.Thread类的使用:

1,在自己的线程类的__init__里调用threading.Thread.__init__(self, name = threadname)

Threadname为线程的名字

2, run(),通常需要重写,编写代码实现做需要的功能。

3,getName(),获得线程对象名称

4,setName(),设置线程对象名称

5,start(),启动线程

6,jion([timeout]),等待另一线程结束后再运行。

7,setDaemon(bool),设置子线程是否随主线程一起结束,必须在start()之前调用。默认为False。

8,isDaemon(),判断线程是否随主线程一起结束。

9,isAlive(),检查线程是否在运行中。

此外threading模块本身也提供了很多方法和其他的类,可以帮助我们更好的使用和管理线程。可以参看http://www.python.org/doc/2.5.2/lib/module-threading.html。

这段时间一直在用 Python 写一个游戏的服务器程序。在编写过程中,不可避免的要用多线程来处理与客户端的交互。 Python 标准库提供了 thread 和 threading 两个模块来对多线程进行支持。其中, thread 模块以低级、原始的方式来处理和控制线程,而 threading 模块通过对 thread 进行二次封装,提供了更方便的 api 来处理线程。 虽然使用 thread 没有 threading 来的方便,但它更灵活。今天先介绍 thread 模块的基本使用,下一篇 将介绍 threading 模块。

在介绍 thread 之前,先看一段代码,猜猜程序运行完成之后,在控制台上输出的结果是什么?

函数将创建一个新的线程,并返回该线程的标识符(标识符为整数)。参数 function 表示线程创建之后,立即执行的函数,参数 args 是该函数的参数,它是一个元组类型;第二个参数 kwargs 是可选的,它为函数提供了命名参数字典。函数执行完毕之后,线程将自动退出。如果函数在执行过程中遇到未处理的异常,该线程将退出,但不会影响其他线程的执行。 下面是一个简单的例子:

结束当前线程。调用该函数会触发 SystemExit 异常,如果没有处理该异常,线程将结束。

返回当前线程的标识符,标识符是一个非零整数。

在主线程中触发 KeyboardInterrupt 异常。子线程可以使用该方法来中断主线程。下面的例子演示了在子线程中调用 interrupt_main ,在主线程中捕获异常 :

下面介绍 thread 模块中的琐,琐可以保证在任何时刻,最多只有一个线程可以访问共享资源。

thread.LockType 是 thread 模块中定义的琐类型。它有如下方法:

获取琐。函数返回一个布尔值,如果获取成功,返回 True ,否则返回 False 。参数 waitflag 的默认值是一个非零整数,表示如果琐已经被其他线程占用,那么当前线程将一直等待,只到其他线程释放,然后获取访琐。如果将参数 waitflag 置为 0 ,那么当前线程会尝试获取琐,不管琐是否被其他线程占用,当前线程都不会等待。

释放所占用的琐。

判断琐是否被占用。

现在我们回过头来看文章开始处给出的那段代码:代码中定义了一个函数 threadTest ,它将全局变量逐一的增加 10000 ,然后在主线程中开启了 10 个子线程来调用 threadTest 函数。但结果并不是预料中的 10000 * 10 ,原因主要是对 count 的并发操作引来的。全局变量 count 是共享资源,对它的操作应该串行的进行。下面对那段代码进行修改,在对 count 操作的时候,进行加琐处理。看看程序运行的结果是否和预期一致。修改后的代码:

thread模块是不是并没有想像中的那么难!简单就是美,这就是Python。更多关于thread模块的内容,请参考Python手册 thread 模块

上一篇 介绍了thread模块,今天来学习Python中另一个操作线程的模块:threading。threading通过对thread模块进行二次封装,提供了更方便的API来操作线程。今天内容比较多,闲话少说,现在就开始切入正题!

Thread 是threading模块中最重要的类之一,可以使用它来创建线程。有两种方式来创建线程:一种是通过继承Thread类,重写它的run方法;另一种是 创建一个threading.Thread对象,在它的初始化函数(__init__)中将可调用对象作为参数传入。下面分别举例说明。先来看看通过继承 threading.Thread类来创建线程的例子:

在代码中,我们创建了一个Counter类,它继承了threading.Thread。初始化函数接收两个参数,一个是琐对象,另一个是线程 的名称。在Counter中,重写了从父类继承的run方法,run方法将一个全局变量逐一的增加10000。在接下来的代码中,创建了五个 Counter对象,分别调用其start方法。最后打印结果。这里要说明一下run方法 和start方法: 它们都是从Thread继承而来的,run()方法将在线程开启后执行,可以把相关的逻辑写到run方法中(通常把run方法称为活动[Activity]。);start()方法用于启动线程。

再看看另外一种创建线程的方法:

在这段代码中,我们定义了方法doAdd,它将全局变量count 逐一的增加10000。然后创建了5个Thread对象,把函数对象doAdd 作为参数传给它的初始化函数,再调用Thread对象的start方法,线程启动后将执行doAdd函数。这里有必要介绍一下 threading.Thread类的初始化函数原型:

def __init__(self, group=None, target=None, name=None, args=(), kwargs={})

参数group是预留的,用于将来扩展;

参数target是一个可调用对象(也称为活动[activity]),在线程启动后执行;

参数name是线程的名字。默认值为“Thread-N“,N是一个数字。

参数args和kwargs分别表示调用target时的参数列表和关键字参数。

Thread类还定义了以下常用方法与属性:

用于获取和设置线程的名称。

获取线程的标识符。线程标识符是一个非零整数,只有在调用了start()方法之后该属性才有效,否则它只返回None。

判断线程是否是激活的(alive)。从调用start()方法启动线程,到run()方法执行完毕或遇到未处理异常而中断 这段时间内,线程是激活的。

调用Thread.join将会使主调线程堵塞,直到被调用线程运行结束或超时。参数timeout是一个数值类型,表示超时时间,如果未提供该参数,那么主调线程将一直堵塞到被调线程结束。下面举个例子说明join()的使用:

在threading模块中,定义两种类型的琐:threading.Lock和threading.RLock。它们之间有一点细微的区别,通过比较下面两段代码来说明:

这两种琐的主要区别是:RLock允许在同一线程中被多次acquire。而Lock却不允许这种情况。注意:如果使用RLock,那么acquire和release必须成对出现,即调用了n次acquire,必须调用n次的release才能真正释放所占用的琐。

可以把Condiftion理解为一把高级的琐,它提供了比Lock, RLock更高级的功能,允许我们能够控制复杂的线程同步问题。threadiong.Condition在内部维护一个琐对象(默认是RLock),可 以在创建Condigtion对象的时候把琐对象作为参数传入。Condition也提供了acquire, release方法,其含义与琐的acquire, release方法一致,其实它只是简单的调用内部琐对象的对应的方法而已。Condition还提供了如下方法(特别要注意:这些方法只有在占用琐 (acquire)之后才能调用,否则将会报RuntimeError异常。):

wait方法释放内部所占用的琐,同时线程被挂起,直至接收到通知被唤醒或超时(如果提供了timeout参数的话)。当线程被唤醒并重新占有琐的时候,程序才会继续执行下去。

唤醒一个挂起的线程(如果存在挂起的线程)。注意:notify()方法不会释放所占用的琐。

唤醒所有挂起的线程(如果存在挂起的线程)。注意:这些方法不会释放所占用的琐。

现在写个捉迷藏的游戏来具体介绍threading.Condition的基本使用。假设这个游戏由两个人来玩,一个藏(Hider),一个找 (Seeker)。游戏的规则如下:1. 游戏开始之后,Seeker先把自己眼睛蒙上,蒙上眼睛后,就通知Hider;2. Hider接收通知后开始找地方将自己藏起来,藏好之后,再通知Seeker可以找了; 3. Seeker接收到通知之后,就开始找Hider。Hider和Seeker都是独立的个体,在程序中用两个独立的线程来表示,在游戏过程中,两者之间的 行为有一定的时序关系,我们通过Condition来控制这种时序关系。

Event实现与Condition类似的功能,不过比Condition简单一点。它通过维护内部的标识符来实现线程间的同步问题。 (threading.Event和.NET中的System.Threading.ManualResetEvent类实现同样的功能。)

堵塞线程,直到Event对象内部标识位被设为True或超时(如果提供了参数timeout)。

将标识位设为Ture

将标识伴设为False。

判断标识位是否为Ture。

下面使用Event来实现捉迷藏的游戏(可能用Event来实现不是很形象)

threading.Timer是threading.Thread的子类,可以在指定时间间隔后执行某个操作。下面是Python手册上提供的一个例子:

threading模块中还有一些常用的方法没有介绍:

获取当前活动的(alive)线程的个数。

获取当前的线程对象(Thread object)。

获取当前所有活动线程的列表。

设置一个跟踪函数,用于在run()执行之前被调用。

设置一个跟踪函数,用于在run()执行完毕之后调用。

threading模块的内容很多,一篇文章很难写全,更多关于threading模块的信息,请查询Python手册 threading 模块。

标签:

原文地址:http://www.cnblogs.com/x113/p/4735385.html