It was and still is, however, relevant with HDD RAID storage – technology we have been using for many years – when there’s striping like in RAID0, 5, 6 or any variation of them (5+0, 1+0, 1+0+0 etc.). While IO inside the RAID is perfectly aligned to disk sectors (again due to the fact operations are done in multiples of 512-bytes), outside of the RAID you want to align IO to a stripe element as you may otherwise end up reading or writing to more disks than you would like to. I decided to do some benchmarks on a hard disk array and see when this matters and whether it matters at all.

In this article I will however focus on the process of alignment, if you’re curious about benchmark results, here they are.

What is IO alignment

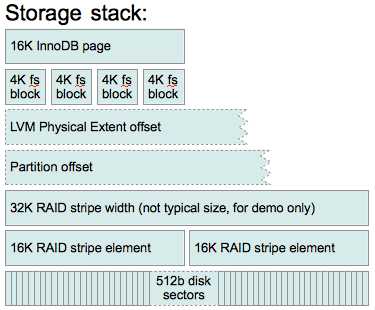

I would like to start with some background on IO alignment. So what is IO alignment and how does a misaligned IO look like? Here is one example of it:

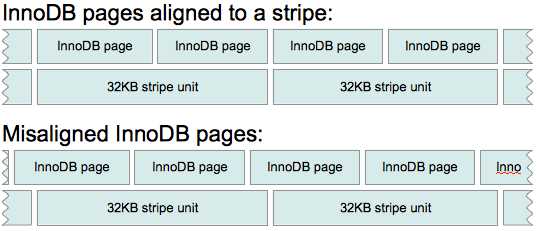

In this case the RAID controller is using 32KB stripe unit and that can fit in 2 standard InnoDB pages (16KB in size) as long as they are aligned properly. In first case when reading or writing a single InnoDB page RAID will only read or write to a single disk because of the alignment to a stripe unit. In the second example however every other page spans two disks so there is going to be twice as many operations to read or write these pages which could mean more waiting in some cases and more work for the RAID controller for that same operation. In practice stripes by default are bigger in size – I would often see see 64KB (mdadm default chunk size) or 128KB stripe unit size so in these cases there would be fewer pages spanning multiple disks so the effects of misalignment would be less significant.

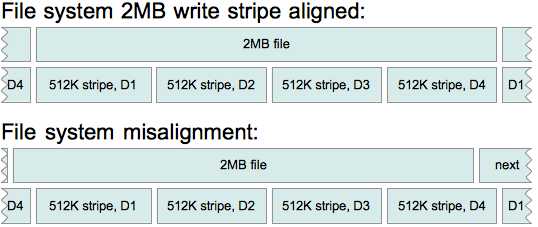

Here’s another example of misalignment, described in SGI xfs training slides:

D stands for the disk here so the RAID has 4 bearing disks (spindles) and if there’s a misalignment on the file system, you can see how RAID ends up doing 5 IO operations – two to D4 and one on each of the other three disks instead of just doing one IO to each of the disks. In this case even if this is the single IO request from OS, it’s guaranteed to be slower both for reading and writing.

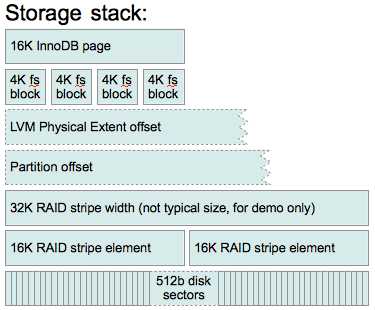

So, how do we avoid misalignment? Well, we must ensure alignment on each layer of the stack. Here’s how a typical stack looks like:

Let’s talk about each of them briefly:

InnoDB page

You don’t need to do anything to align InnoDB pages – file system takes care of it (assuming you configure the file system correctly). I would however mention couple things about InnoDB storage: first – in Percona Server you can now customize page size and it may be good idea to check that page size is no bigger than stripe element; second – logs are actually written in 512 byte units (in Percona Server 5.1 and 5.5 you can customize this) while I will be talking here about InnoDB data pages which are 16KB in size.

File system

File system plays very important role here – it maps files logical address to physical address (at a certain level) so when writing a file, file system decides how to distribute writes properly so they make the best use of the underlying storage, it also makes sure file starts in a proper position with respect to stripe size. The size of logical IO units also is up to the file system.

The goal is to write and read as little as possible. If you gonna be writing small (say 500 byte) files mostly, it’s best to use 512-byte blocks, for bigger files 4k may make more sense (you can’t use blocks bigger than 4k (page size) on Linux unless you are using HugePages). Some file systems let you set stripe width and stripe unit size so they can do a proper alignment based on that. Mind however that different file systems (and different versions of them) might be using different units for these options so you should refer to a manual on your system to be sure you’re doing the right thing.

Say we have 6-disk RAID5 (so 5 bearing disks) with 64k stripe unit size and 4k file system block size, here’s how we would create the file system:

|

1

2

|

xfs - mkfs.xfs -b size=4k -d su=64k,sw=5 /dev/ice (alternatively you can specify sunit=X,swidth=Y as options when mounting the device)

ext2/3/4 - mke2fs -b 4096 -E stride=16,stripe-width=80 /dev/ice (some older versions of ext2/3 do not support stripe-with)

|

You should be all set with the file system alignment at this point. Let’s get down one more level:

LVM

If you are using LVM, you want to make sure it does not introduce misalignment. On the other hand it can be used to fix it if it was misaligned on the partition table. On the system that I have been benchmarking, defaults worked out just fine because I was using a rather small 64k stripe element. Have I used 128k or 256k RAID stripe elements, I would have ended up with LVM physical extent starting somewhere in the middle of the stripe which would in turn screw up file system alignment.

You can only set alignment options early in the process when using pvcreate to initialize disk for LVM use, the two options you are interested in are –dataalignment and –dataalignmentoffset. If you have set the offset correctly when creating partitions (see below), you don’t need to use –dataalignmentoffset, otherwise with this option you can shift the beginning of data area to the start of next stripe element. –dataalignment should be set to the size of the stripe element – that way the start of a Physical Extent will always align to the start of the stripe element.

In addition to setting correct options for pvcreate it is also a good idea to use appropriate Volume Group Physical Extent Size for vgcreate – I think default 4MB should be good enough for most cases, when changing however, I would try to not make it smaller than a stripe element size.

To give you a bit more interesting alignment example, let’s assume we have a RAID with 256k stripe element size and a misalignment in partition table – partition /dev/sdb1 starts 11 sectors ahead of the stripe element start (reminder: 1 sector = 512 bytes). Now we want to get to the beginning of next stripe element i.e. 256th kbyte so we need to offset the start by 501 sectors and set proper alignment:

|

1

|

pvcreate --dataalignmentoffset 501s --dataalignment 256k /dev/sdb1

|

You can check where physical extents will start (or check your current setup) using pvs -o +pe_start. Now let’s move down one more level.

Partition table

This is the most frustrating part of the IO alignment and I think the reason people get frustrated with it is that by default fdisk is using “cylinders” as units instead of sectors. Moreover, on some “older” systems like RHEL5 it would actually align to “cylinders” and leave first “cylinder” blank. This comes from older times when disks were really small and they were actually physical disks. Drive geometry displayed here is not real- this RAID does not really have 255 heads and 63 sectors per track:

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

|

db2# fdisk -l

Disk /dev/sda: 1198.0 GB, 1197998080000 bytes

255 heads, 63 sectors/track, 145648 cylinders

Units = cylinders of 16065 * 512 = 8225280 bytes

...

Device Boot Start End Blocks Id System

/dev/sda1 * 1 1216 9764864 83 Linux

/dev/sda2 1216 1738 4194304 82 Linux swap / Solaris

Partition 2 does not end on cylinder boundary.

/dev/sda3 1738 145649 1155959808 83 Linux

Partition 3 does not end on cylinder boundary.

|

So it makes a lot more sense to use sectors with fdisk these days which you can get with -u when invoking it or with “u” when working in the interactive mode:

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

|

db2# fdisk -ul

Disk /dev/sda: 1198.0 GB, 1197998080000 bytes

255 heads, 63 sectors/track, 145648 cylinders, total 2339840000 sectors

Units = sectors of 1 * 512 = 512 bytes

...

Device Boot Start End Blocks Id System

/dev/sda1 * 2048 19531775 9764864 83 Linux

/dev/sda2 19531776 27920383 4194304 82 Linux swap / Solaris

Partition 2 does not end on cylinder boundary.

/dev/sda3 27920384 2339839999 1155959808 83 Linux

Partition 3 does not end on cylinder boundary.

|

The rest of the task is easy – you just have to make sure that Start sector divides by number of sectors in a stripe element without a remainder. Let’s check if /dev/sda3 aligns to 1MB stripe element. 1MB is 2048 sectors, dividing 27920384 by 2048 we get 13633 so it does align to 1MB boundary.

Recent systems like RHEL6 (not verified) and Ubuntu 10.04 (verified) would by default align to 1MB if storage does not support IO alignment hints which is good enough for most cases, however here’s what I got on Ubuntu 8.04 using defaults (you would get the same on RHEL5 and many other systems):

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

|

db1# fdisk -ul

Disk /dev/sda: 1197.9 GB, 1197998080000 bytes

255 heads, 63 sectors/track, 145648 cylinders, total 2339840000 sectors

Units = sectors of 1 * 512 = 512 bytes

Disk identifier: 0x00091218

Device Boot Start End Blocks Id System

/dev/sda1 * 63 19535039 9767488+ 83 Linux

/dev/sda2 19535040 27342629 3903795 82 Linux swap / Solaris

/dev/sda3 27342630 2339835119 1156246245 8e Linux LVM

|

sda1 and sda3 do not even align to 1k. sda2 aligns up to 32k but the RAID controller actually has 64k stripe so all IO on this system is unaligned (unless compensated by LVM, see above). So on such a system, when creating file systems with fdisk, don’t use the default value for a start sector, instead use the next number that divides by the number of sectors in a stripe element without a reminder and make sure you’re using sectors as units to simplify the math.

Besides DOS partition table which you would typically work with using fdisk (or cfdisk, or sfdisk), there’s also a more modern – GUID partition table (GPT). The tool for the task of working with GPT is typically parted. If you are already running GPT on your system and want to check if it’s aligned, here’s a command for you:

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

|

db2# parted /dev/sda unit s print

Model: LSI MegaRAID 8704EM2 (scsi)

Disk /dev/sda: 2339840000s

Sector size (logical/physical): 512B/512B

Partition Table: msdos

Number Start End Size Type File system Flags

1 2048s 19531775s 19529728s primary ext4 boot

2 19531776s 27920383s 8388608s primary linux-swap(v1)

3 27920384s 2339839999s 2311919616s primary

|

This is the same output we saw from fdisk earlier. Again you want to look at Start sector and make sure it divides by the size of stripe element without a reminder.

Lastly, if this is not a system boot disk you are working on, you may not need partition table at all – you can just use the whole raw /dev/sdb and either format it with mkfs directly or add it as an LVM physical volume. This let’s you avoid any mistakes when working on partition table.

RAID stripe

Further down below on the storage stack there’s a group of RAID stripe units (elements) sometimes referred to as a stripe though most of the tools refer to it as a stripe width. RAID level, number of disks and the size of a stripe element set the stripe width size. In case of RAID1 and JBOD there’s no striping, with RAID0 number of bearing disks is actual number of disks (N), with RAID1+0 (RAID10) it’s N/2, with RAID5 – N-1 (single parity), with RAID6 – N-2 (double parity). You want to know that when setting parameters for file system but when RAID is configured, there’s nothing more you can do about it – you just need to know these.

Stripe unit size is the amount of data that will be written to single disk before skipping to next disk in the array. This is also one of the options you usually have to decide on very early when configuring RAID.

Disk sectors

Most if not all hard disk drives available on the market these days use 512-byte sectors so most of the time if not always you don’t care about alignment at this level and nor do RAID controllers as they also operate in 512-bytes internally. This however gets more complicated with SSD drives which often operate in 4kbyte units, though this is surely a topic for another research.

Summary

While it may seem there are many moving parts between the database and actual disks, it’s not really all that difficult to get a proper alignment if you’re careful when configuring all of the layers. Not always however you have a fully transparent system – for example in the cloud you don’t really know if the data is properly aligned underneath: you don’t know if you should be using an offset, what stripe size and how many stripe elements. It’s easy to check if you’re aligned – run a benchmark with an offset and compare to a base, but it’s much harder to figure out proper alignment options if you are not aligned.

Now it may be interesting to see what are real life effects of misalignment, my benchmark results are in the second part.